Every week of the year has its own Torah portion (a reading from the first five books of the Bible) and its own haftarah (an accompanying reading from the books of the prophets). This week the Torah portion is Eikev (Deuteronomy 7:12-11:25) and the haftarah is Isaiah 49:14-51:3).

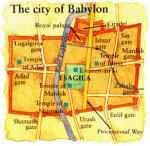

When the Babylonians burned down Jerusalem and its temple in 586 B.C.E., they also deported the last of its leading families to Babylon. They were not allowed not leave until the Persian Empire swallowed the Babylonian Empire 47 years later, and the Persian king Cyrus declared freedom of movement and freedom of religion.

Psalm 137, like this week’s haftarah from second Isaiah, is about the Babylonian Exile:

How can we sing a song of God

On foreign soil?

If I forget you, Jerusalem

May I forget my right hand. (Psalm 137:4-5)

In Jewish history, which spans millennia, 47 years may not seem long. But for individuals it was a long time to remember their old home and their old god—especially if they were born in Babylon, and had only their elders’ memories to go by.

“Why did I come and there was nobody,

[Why] did I call and there was no answer?” (Isaiah 50:2)

Usually when someone in the Hebrew Bible cries “Why have you forsaken me?” it is an Israelite addressing God. But in this week’s haftarah, God cries out, feeling forsaken by the Israelites who have adjusted to life in Babylon.

In the second book of Isaiah, God is preparing to end the rule of the Babylonian empire, rescue the Israelite exiles, and return them to Jerusalem and their own land. (See my post: Haftarah for Va-etchannan—Isaiah: Who Is Calling?) But God’s plans are useless unless the Israelites trust their God and want to go home.

Imagine you were kidnapped and taken to a strange city. Your life there was comfortable, but you were not free to leave. Would you accept your new reality, adopt the customs and religion of the city, and make it your home?

This must have been the strategy of the Israelites that the Assyrian armies deported from Samaria, the capital of the northern kingdom of Israel, in 729-724 B.C.E.—because the Bible never mentions them again. They either died or assimilated.

Or would you cling to your memories and your old religion, hoping that someday you would escape and go home?

This is the strategy that the second book of Isaiah advocates for the Israelites living in Babylon.

Reading between the lines, I imagine some Israelites moved past their trauma, married Babylonians, and settled down for good. I imagine others were stuck with post-traumatic stress disorder, trying hard not to remember their old lives or God or Jerusalem. And I imagine some stubborn individuals clinging to the belief that their God was alive and well, and would someday rescue them and return them to their motherland.

But how could the believers convince their fellow Israelites to take heart and wait for God?

This week’s haftarah tries a new approach: Stop thinking about yourselves, and remember the parents you left behind: your homeland, which is like a mother, and your God, who is like a father. How do they feel?

The haftarah begins with the land—called Zion for one of the hills in Jerusalem—crying that God has forsaken her, too.

And Zion says:

God has abandoned me,

And my lord has forgotten me! (Isaiah 49:14)

So far, Zion and God sound like lovers. But this is not another example of the prophetic poetry claiming that the people of Israel are straying after other gods like a wife who is unfaithful to her husband. In this haftarah, the innocent land is Zion, and the people are Zion’s children. Zion lies in ruins after the war, empty and desolate because her destroyers (the Babylonians) stole all her children.

God reassures Zion by telling her:

Hey! I will lift up My hand to nations

And raise My banner to peoples,

And they shall bring your sons on their bosoms

And carry your daughters on their shoulders. (Isaiah 49:22)

In this poem God will arrange for foreigners (like King Cyrus) to return Zion’s children to Jerusalem. The poet or poets who wrote second Isaiah probably hoped that if discouraged exiles thought of Jerusalem as a mother missing her children and longing to have them back, their hearts might soften, and they might want to return to her.

Then, second Isaiah says, they would hear God ask:

Why did I come and there was nobody,

[Why] did I call and there was no answer?

Is my hand short, too short for redemption?

And is there no power in me to save? (Isaiah 50:2)

What if the “children of Zion” only thought their god, their father, had been defeated when the Babylonian army destroyed Jerusalem? What if God had actually planned the exile to punish them, as Jeremiah kept prophesying during the siege? Now that the punishment was over, did God miss the people of Judah?

What if their father, their god, really was powerful enough to rescue them and take them home to Zion? (See my post: Haftarat Va-etchanan–Isaiah: Faith in the Creator.)

If both parents, God and Zion, are yearning for them, then the Israelites in Babylon might start yearning for God and Zion again.

*

It worked. After King Cyrus issued his decree, bands of Israelites from Babylon began returning to Jerusalem, a thousand or so at a time. Under Ezra and Nehemiah they built a new, larger temple for God. The former kingdom of Judah became a Persian province administered by Jews, and the expanded, monotheistic version of their religion, founded by second Isaiah, survived.

Today, two and a half millennia later, yearning for Jerusalem is built into Jewish daily liturgy. At the end of the Passover seder in the spring and Yom Kippur services in the autumn we even sing out: “Next year in Jerusalem!”

Almost half of the Jews in the world today live in the United States. We are free to emigrate to the nation of Israel, as long as we meet Israel’s requirements. Only a few do so. Are religious American Jews still exiles?

Or has God become both the mother and the father we yearn for, while Jerusalem is now a pilgrimage site?