What does it mean to be stripped naked and exposed in public? Joseph finds out—twice—in this week’s Torah portion, Vayeishev (“And he stayed”).

When Joseph is growing up, his father, Jacob, treats him as superior to all ten of his older brothers. Naturally his brothers are jealous. They also hate Joseph because he tells them his two dreams, both of which predict his brothers will bow down to him.

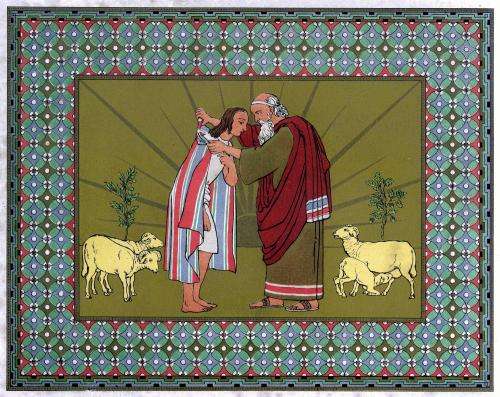

Jacob makes things worse by giving a special garment only to his favorite son, Joseph.

…and he made for him a ketonet passim. And his brothers saw that it was he their father loved most out of all his brothers, so they hated him, and they were not able to speak to him with peace. (Genesis/Bereishit 37:3-4)

ketonet = a long tunic

passim = ? (Newer translations include “ornamented” and “long-sleeved”. Pas = palm of hand (or sole of foot). A garment with sleeves below the wrist would be impractical for physical labor, and therefore a sign of high rank. The only other biblical reference to passim is in 2 Samuel 13:18-19, which explains that King David dresses his unmarried daughters in katenot passim.)

The King James Bible translated ketonet passim, inaccurately, as a “coat of many colors”. I wonder if the translators chose the word “coat” in order to imply that Jacob is fully dressed underneath the garment his brothers strip off. But a coat or cloak would be a simlah or me-iyl in biblical Hebrew, not a ketonet. And as far as we know, nothing was worn under a ketonet.

Jacob sends Joseph to check up on his brothers, who are pasturing the family flocks far away in Dotan. Although Joseph knows his brothers “could not speak to him in peace” (Genesis 37:4), he does not imagine that while they watch him approach they are debating whether to kill him.

And so it was, when Joseph came to his brothers, then they stripped off Joseph his ketonet, the ketonet of the passim, which was on him. And they took him and threw him down into the pit; and the pit was empty, there was no water in it. (Genesis 37:23-24)

The brothers decide to sell Joseph as a slave instead of killing him. They have no trouble selling him to a passing merchant caravan; a naked adolescent boy at the bottom of an empty cistern is unlikely to be anyone of importance. When the merchants reach Egypt, they resell Joseph to the Pharaoh’s chief butcher, Potifar.

What if you found yourself in a foreign country with no clothes, no money, and no identification, being handed over to your new owner? Would you scream that it was a mistake, and keep trying to explain who you are?

At age 17, Joseph accepts his new situation with remarkable equanimity. He sees that without his father’s ketonet and his father’s authority, he has no identity. Naked, he has only the blessings God gave him at birth: brains and beauty. So he applies his intelligence to his new situation and makes the best of it.

God was with him and he became a successful man, and it happened in the house of his master, the Egyptian. (Genesis 39:2)

Joseph’s master, Potifar, promotes him from field slave to steward of his entire household. Egyptian field slaves worked naked, but a steward would wear a linen kilt called a shenti or shendyt.

Once Joseph is nicely dressed, his beauty attracts Potiphar’s wife. She propositions him day after day, but Joseph refuses her on the grounds that it would be unfair to his master and an offense against God.

A less mature young man would assume his elevation to steward was entirely due to his own cleverness and hard work. But Joseph’s reply to Potifar’s wife shows that he knows he would still be working in the field naked without the goodwill of his human and divine masters.

Then it happened one day, he came into the house to do his work, and none of the men of the house were there inside the house. And she seized him by his beged, saying: Lie with me! But he left his beged in her hand, and he fled and he went outside. (Genesis 39:11-12)

beged = garment (of any kind), clothing, cloth covering; treachery.

Joseph’s wrap-around linen kilt would be tied in front, and if the knot came loose—or were pulled loose by a lustful woman—the garment would fall off onto the floor.

What does an Egyptian wear under his kilt? In the time of the Middle Kingdom, an Egyptian nobleman wore a sheer linen shendyt and a short under-skirt. But Joseph, as a high-ranking slave, would wear a coarse linen shendyt and nothing underneath. When he flees and goes outside, he is naked.

Potifar’s wife is afraid that other servants will see Joseph naked, and find Joseph’s garment in her room. To avoid being accused of adultery, she screams, and then accuses Joseph of imposing himself on her. As a result, Joseph finds himself back in a pit: Potifar sends him to prison.

Once again, Joseph has been stripped of his clothing and his position due to the treachery of someone whom he never suspected would go that far.

Joseph continues to use his brains in prison, and God continues to bless him with success. He becomes the chief jailer’s steward. After two years, Joseph is given an opportunity to interpret the Pharaoh’s dreams, and he succeeds at this, too. Pharaoh elevates him to viceroy of Egypt, and Joseph wears a gold ring and the finest sheer linen. This time he keeps his public identity, along with his clothes.

Clothing still gives people visible status and identity today. We treat a man wearing a suit and tie differently from one wearing a torn sweatshirt. And even today, we might lose our social identities at any time, no matter how wonderful our innate qualities are.

But we increase the odds of keeping our public identities when we treat other people not as clothes hangers, but as human beings with their own feelings and desires. We do better if we are grateful to the Potifars in our lives, and extremely cautious with the jealous brothers and philandering wives.

We are all naked under our clothes. May we all become humble enough, like Joseph, to learn from the times we are exposed, and reinvent our lives for the better.