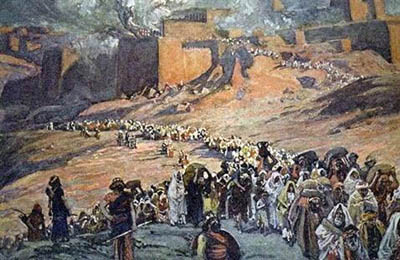

Jews observe a day of mourning every year on Tisha Be-Av, the ninth day of the month of Av. Starting at sunset this Saturday evening, we will once again mourn the destruction of Jerusalem in 587 B.C.E and its temple in 586 B.C.E. by the Babylonian army.

After the Romans destroyed the second temple in 70 C.E., Tisha Be-Av became the day to mourn both events. Over the millennia, the mourning on this day has expanded to include other wholesale catastrophes inflicted on Jews, such as the Crusades, the Spanish Inquisition and Expulsion, and the Nazi Holocaust.

Besides fasting and praying on Tisha Be-Av, the Jewish tradition calls for chanting the book of Lamentations: four poems mourning the Babylonian destruction of Jerusalem, and a poem of personal lamentation in the middle.

What I noticed when I reread Lamentation this year is the theme of death by starvation—the result of the 30-month siege before Jerusalem surrendered to the Babylonians in 587 B.C.E.

Chapter 1: Neglected city

The book of Lamentations is called Eykhah in Hebrew because it opens with that word:

Eykhah she sits in isolation?

The city [once] teeming with people?

She has become like a widow. (Lamentations 1:1)

Eykhah (אֵכָה) = How, where, alas; how can it be?1

After describing the desolation of the razed city, the deportation of some of its survivors, and the lack of allies to help the remaining survivors, the poem says:

All her people are moaning,

searching for bread.

They have given away their treasures for food

to restore their lives.

See, God! And notice

how I have become worthless. (Lamentations 1:11)

The last couplet in this verse switches to first person, from the viewpoint of Jerusalem herself. The city is worthless now. The victims of the siege would also feel worthless, not even worthy of being fed.

I called out to my lovers;

they had deceived me.

My priests and my elders perished in the city

as they searched for food for themselves

to restore their lives.

See, God, that I am in narrow straits!

Mei-ay are in turmoil.

My heart is turning over inside me,

for I have surely rebelled.

Outside, the sword bereaves;

in the house, it is like death. (Lamentations 1:19-20)

mei-ay (מֵעַי) = my bowels, my innards; my inner feelings.

“My lovers” refers to the kingdom of Judah’s erstwhile allies, who abandoned it when the Babylonian army began its conquest. “My priests and my elders” are the religious leaders and judges who were formerly sustained by public funding. “Bowels in a turmoil” could be a literal description of a symptom of malnutrition, or a reference to extreme anxiety.

“I have surely rebelled” is one of many lines in Lamentations which reflect the biblical assumption that the victims must have done something wrong, or God would not have let the devastation happen. (See my post: Isaiah & Lamentations: Any Hope?) In this first poem the city has surrendered and the siege is over, but the deaths continue. The last two lines refer to Jerusalemites being slain by enemy soldiers in the streets, while people inside their houses are still dying of the diseases caused by slow starvation.

Chapter 2: Starving children

The second poem in Lamentations points out the fate of children in Jerusalem.

My eyes are consumed with tears,

mei-ay are in turmoil.

Keveidi pours out on the ground,

over the shattering of my people.

Small child and nursing baby are fainting

in the plazas of the city. (Lamentations 2:11)

keveidi (כְּבֵדִי) = my liver (the heaviest organ in the body). From the same root as the adjective kaveid (כָּבֵד) =heavy, weighty, oppressive, impressive; and theverb kaveid (כָּבֵד) = was heavy, was honored.

The speaker’s liver is not literally pouring out on the ground. The person full of tears and inner turmoil either finds the situation either unbearably heavy and oppressive, or has lost any hope of being honorable.

The poem continues:

They say to their mothers:

“Where is grain and wine?”

While they faint like the fatally wounded

in the plazas of the city,

As their life pours out in their mothers’ bosoms. (Lamentations 2:12)

After a digression criticizing the enemies of the almost-conquered kingdom of Judah, the poet cries out to Jerusalem:

Get up! Sing out in the night

at the beginnings of the watches,

Pour out your heart like water

in front of our Lord!

Raise your palms to God

over the life of your small children,

Who faint with hunger

at every street corner! (Lamentations 2:19)

The poet even raises the threat that people might commit what the Hebrew Bible considers the most horrible kind of cannibalism: a mother eating her own child.

See, God, and notice

to whom you are ruthless!

If women eat their own fruit,

children [they once] fondled?

If priest and prophet are killed

in the holy place of God? (Lamentations 2:20)

But in the book of Lamentations, God never responds.

Chapter 4: Slow death

After the third poem in Lamentations, a first-person lament that does not mention Jerusalem, the fourth poem returns to stirring sympathy for the innocent children caught in the siege.

The tongue of the nursing baby sticks

to its palate in thirst.

Small children beg for bread;

there is no one to break it for them. (Lamentations 4:4)

Breaking bread is an idiom; we can assume at this point there are no loaves of bread available to break in the besieged city! The poet then describes how the survivors of the long siege have changed.

Her consecrated ones were cleaner than snow,

whiter than milk.

Their limbs were ruddier than coral,

gleaming like sapphire.

[Now] they appear darker than black;

they are not recognized in the streets.

Their skin is shriveled on their bones;

it has become dry as wood. (Lamentations 4:7-8)

Starvation and malnutrition turn people who were once gleaming with good health into black stick-figures. Their shriveled and discolored faces are no longer recognizable. Metaphorically, they are so sick and depleted that they have lost their individuality.

Better those slain by the sword

than slain by famine,

Since those pierced through gush blood

more than the crop of the field. (Lamentations 4:9)

In other words, it is better to die suddenly when one is in good health, losing blood in a rush, than to die gradually by drying up. The Talmud explained: “This one, who dies of famine, suffers greatly before departing from this world, but that one, who dies by the sword, does not suffer.”2

The metaphor of bleeding crops is obscure. Robert Alter suggested: “Run through by the sword, their bodies ooze blood more abundantly than the crop of the field runs with sap (alternately, more than the crop of the field flourishes).”3

The poet then turns to the horror already broached in the second poem:

The hands of compassionate women

cooked their own children!

They were for eating, for them,

during the shattering of my people. (Lamentations 4:10)

Neither reference to cannibalism in Lamentations accuses the mothers of killing their children. After all, children die of starvation much sooner than adults.4 The Talmud viewed a mother’s cannibalism as the most severe punishment from God for whatever sin the Jerusalemites might have committed.5

Chapter 5: Burning

The fifth and final poem in Lamentations sums up what happened, including the lack of food during and after the siege.

At the risk of our lives we gathered our bread

in the face of the sword of the wilderness.

Our skin was hot like a furnace

in the face of burning hunger. (Lamentations 5:9-10)

Rabbi Steinsaltz suggested two possible meanings: “In order to obtain food, we must put our lives at risk by traveling through the desert, which is frequented by robbers. Alternatively: In order to survive during the war we must bring food from faraway places, even from the wilderness.”6

And Robert Alter speculated that the verse about gathering bread referred to Jerusalemites who were fleeing into the desert after Jerusalem surrendered, and faced armed bandits.7 Regardless of the poet’s exact meaning, the two couplets refer to the same alternatives as in the fourth poem: death by the sword, or death by starvation. And the opportunistic diseases that accompany starvation give people high fevers.

War has not ended. There is always somewhere in the world where people are suffering due to destruction, death, and exile inflicted upon them by enemies. In 587 B.C.E., Jerusalem was one of those places. And since the city had been under siege for two and a half years, many of the deaths were due to starvation.

The book of Lamentations begs God for compassion. No one expected the Babylonians to exercise compassion. But whoever deprives innocent people, especially infants and children, of food tortures them to death, and deprives them of their humanity.

Today the Gaza strip has been under siege for almost two years. Hamas started the war, but the government of Israel has continued bombing the enclave. Residents are warned about each new offensive so they can move to another area of the Gaza strip while their homes are ruined. But the distribution of food, clean water, and medical supplies has been hampered rather than encouraged. More and more survivors of the bombs (today’s equivalent of swords) are dying of starvation. What was once true for Jews in Jerusalem is now true for Palestinians in Gaza:

All her people are moaning, searching for bread. (Lamentations 1:11)

Small child and nursing baby are fainting in the plazas of the city … their life pours out in their mothers’ bosoms. (Lamentations 2:11-12)

Eykhah! How can it be?

- For more on Eykhah and the incomprehension at how things could have reached this point, see my post: Devarim, Isaiah, & Lamentations: Desperation.

- Talmud Bavli, Bava Batra 8b.

- Robert Alter, The Hebrew Bible, Volume 3: A Translation with Commentary, W.W. Norton & Co., New York, 2019, p. 665 footnote 9.

- Growing children have higher nutritional needs than adults, and their immune systems are more susceptible to disease and infection. Infants die quickly in a famine because mothers who have not eaten cannot breastfeed them.

- Talmud Bavli, Sanhedrin 104b, translation in www.sefaria.org.

- Rabbi Adin Even-Israel Steinsaltz, Introductions to Tanakh: Lamentations, quoted in www.sefaria.org.

- Alter, p. 668 footnote 9.