If you want to read one of my earlier posts on this week’s Torah portion, Nitzavim (Deuteronomy 29:9-30:20) you might try: Nitzavim: From Mouth to Heart. If you want to read one of my posts on Rosh Hashanah, which begins on the evening of September 22 in 2025 (as we welcome the Jewish year of 5786), you might try: Rosh Hashanah: Remembering.

But if you want to read my next post in the series about why David is God’s beloved, I’m afraid you’ll have to wait until next week.

Right now I’m getting ready for September 17. In the afternoon I will be giving a talk on Rosh Hashanah, and in the evening I will join three collaborators for a book launch event in Portland, Oregon, for:

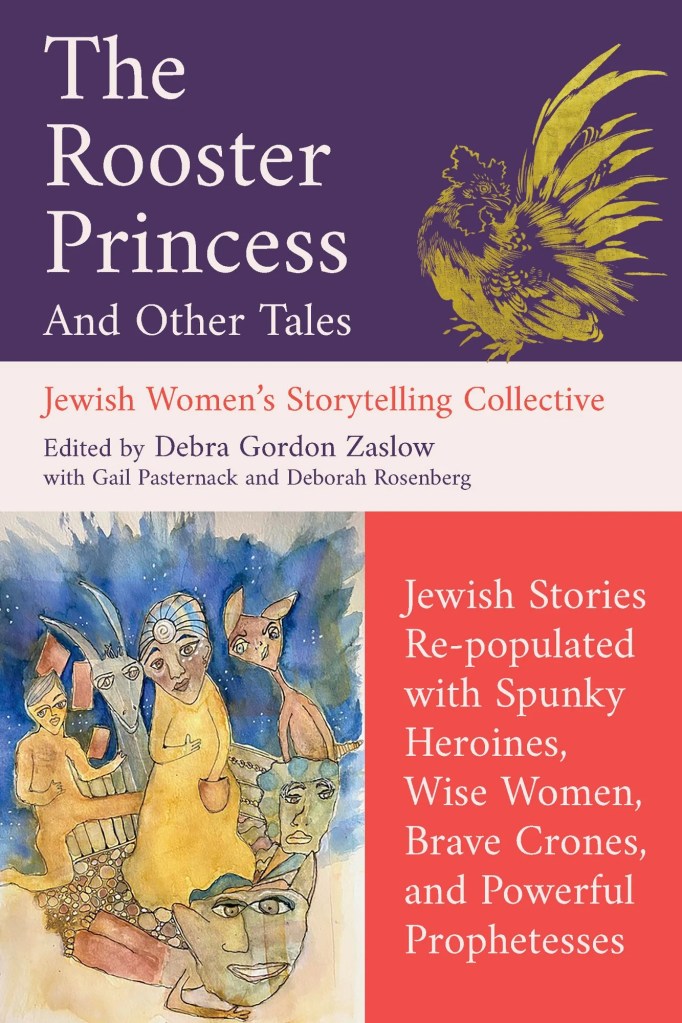

The Rooster Princess and Other Tales, Monkfish Book Publishing, Sept. 2025.

Every story in this groundbreaking anthology by The Jewish Women’s Storytelling Collective has a female protagonist. Some are original stories, some are old Jewish tales rewritten with a new perspective. My own contribution is a Torah monologue from the viewpoint of the prophetess Miriam, sister of Moses and Aaron.

The books are available at powells.org, bookshop.org, and Amazon.com, or at our local readings.

If you are in Portland, please join me (Maggidah Melissa Carpenter), Rabbi Rivkah Coburn, Maggidah Gail Pasternak, Maggidah Cassandra Sagan, and Maggidah Debra Zaslow for one of our first two readings/storytellings:

Wednesday, September 17th, 7:00 pm, at Eastside Jewish Commons, 2420 NE Sandy Blvd.

Monday, October 6, 7:00 pm, at Annie Bloom’s Books, 7834 SW Capitol Hwy.