Take a week or two off work and out of your home. Spend it doing things you never do the rest of the year. When you come back from your vacation, it may be hard to resume your usual life. How do you return to normal?

This is the question Jews have faced for millennia in the month of Tishrei, the lunar month that falls in September or October in the Gregorian calendar.

- 1 & 2 Tishrei: Rosh Hashanah, a new year observance with two days of services.

- 10 Tishrei: Yom Kippur, a full day of fasting and praying for our misdeeds of the past year to be forgiven, and for God to enroll us for a good life in the new year..

- 15-21 Tishrei: Sukkot.

- 21 Tishrei: Hoshana Rabbah, the last day of Sukkot. (Friday, October 6 in 2023.)

- 22 Shemini Atzeret.

- 23 Simchat Torah.

And then, suddenly, life as usual resumes.

Sukkot Elaborations

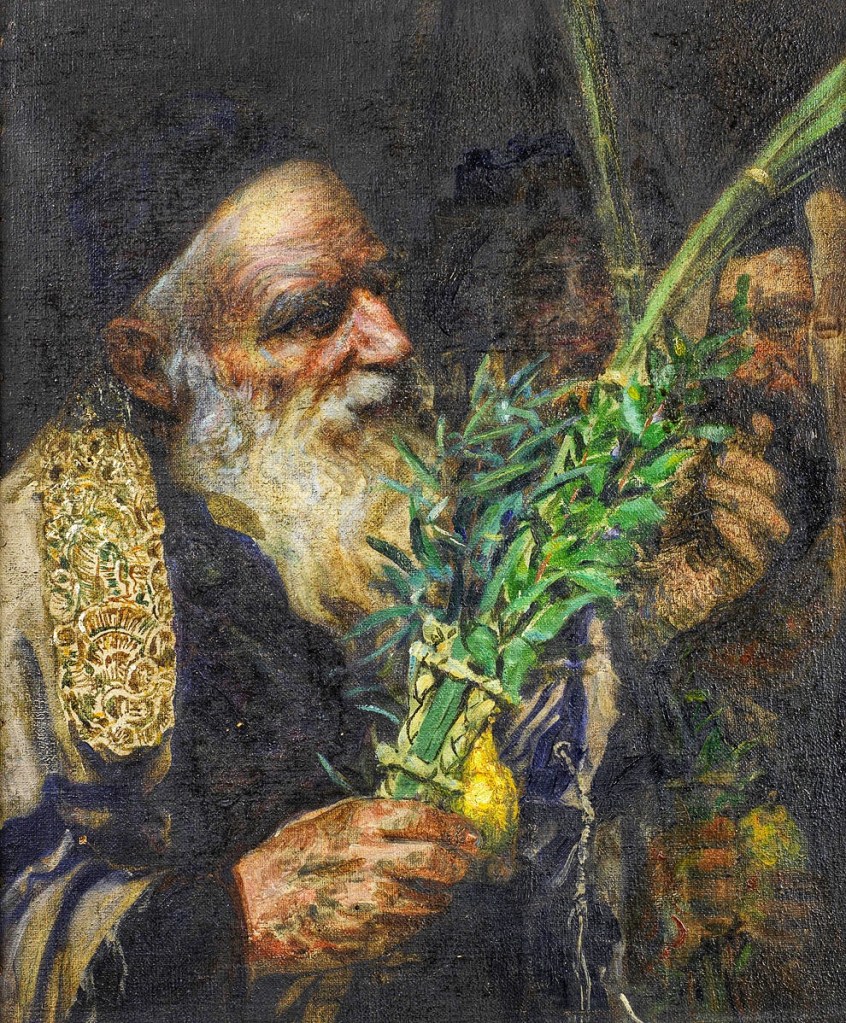

The Torah describes Sukkot both as a week for making animal, grain, and wine offerings at the altar in Jerusalem,1 and as a week for living in a sukkah (a temporary hut with a porous roof of branches or straw) and doing something unspecified with an etrog (a yellow citrus fruit) and branches from palm, myrtle, and willow trees (later bound together and called a lulav).2 (See last week’s post, Sukkot: Rootless.)

The Talmud reports that during the time of the second temple in Jerusalem, many people brought their lulav and etrog to an additional festivity at the temple: the pouring of a water libation every evening.

One who did not see the Celebration of the Place of the Drawing of the Water never saw celebration in his days. (Talmud Bavli, Sukkah 51a)3

An elaborate procession brought a large golden jug of water from the Siloam Pool at the southern end of Jerusalem to the top of the temple mount and up the ramp to the altar, while Levites played flutes and priests blew the shofar. There were so many oil lamps on poles in the temple courtyards that the whole city was lit up.

And the Levites would play on lyres, harps, cymbals, and trumpets, and countless other musical instruments. The musicians would stand on the fifteen stairs that descend from the Israelite [Men’s] Courtyard to the Women’s Courtyard. (Talmud Bavli, Sukkah 51a)

The high priest poured the water into a basin as a libation for God. Men danced and juggled flaming torches.

One time a Sadducee priest intentionally poured the water on his feet, as the Sadducees did not accept the oral tradition requiring water libation, and in their rage all the people pelted him with their etrogim.4 (Talmud Bavli, Sukkah 48b)

The water-pouring celebration, as well as the offerings at the altar, ceased when the Romans razed the second temple in 70 C.E. But to this day, many Jews continue to spend the week of Sukkot eating and even sleeping in a festively decorated sukkah, and ritually shaking a lulav and etrog in six directions, an ancient ritual to encourage the rainy season to begin.

Hoshana Rabbah

In the Torah there is nothing special about the seventh day of Sukkot except a change in the number of animals to offer at the temple altar.5 But the Talmud relates an additional change in observance. The Talmudic rabbis recall that at the start of Sukkot, cut willow branches were placed upright on the platform of the altar, so they leaned over the edge at the top. On each of the first six days of Sukkot, priests blew signal on the shofar, and people walked in a circle around the altar, chanting two lines from Psalm 118:

I beg you, God, hoshiyah, na!

I beg you, God, make us prosper, na! (Psalm 118:25)

hoshiyah (הוֹשִׁיעָה) = Rescue! Save! (An imperative hifil form of the verb yasha, ישׁע = help, save, liberate.)

na (נָא) = please!

On the seventh day of Sukkot, people circled the altar not once, but seven times.6 This practice became incorporated into an additional morning prayer on Sukkot that begins with and repeats the words hosha na (הוֹשַׁע נָא), an Aramaic version of hoshiyah na. While chanting this prayer, congregants holding a lulav make a circuit around the sanctuary (at least in congregations that hold daily morning services during Sukkot).

The last day of Sukkot is called Hoshana Rabbah, when people circle seven times, and then strike the floor with willow branches until the leaves fall off—perhaps evoking either the change of season, or the final discarding of the old year’s misdeeds.

Shemini Atzeret

The last day of Sukkot is Hoshana Rabbah. Yet both Leviticus7 and Numbers mandate an eighth holy day. The Torah gives no explanation for this day, but merely lists the required offerings at the temple.

On the day of Shemini Atzeret, you must not you must not work at your occupations. And you must present a fire-offering, a soothing smell for God: one bull, one ram, seven yearling lambs, unblemished; your grain-offerings and your libations for the bull, the ram, and the lambs, by the legal count; and one hairy goat [for a] guilt-offering, aside from the perpetual rising-offering and its grain offering and libation. (Numbers 29:35-38)

shemini (שְׁמִינִי) = eighth.

atzeret (עֲצֶֶרֶת) = holding back; festive gathering while refraining from work. (From the verb atzar, עָצַר = hold back, detain, retain, be at a standstill.)

The Talmud paints Shemini Atzeret as a quieter day than any day of Sukkot, since there was no water-pouring, and people were not even required to sit in a sukkah or hold a lulav and etrog.8 All they did was remain in Jerusalem for one more round of offerings at the temple.

Then what could Jews do to observe Shemini Atzeret after the second temple was razed in 70 C.E?

19th-century rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch considered Shemini Atzeret a day of reflection. “Its purpose is to keep us before God … in order to strengthen our grasp of perceptions we have already gained, so that they remain with us for a long time. … on this day we gather up and hold fast to all the spiritual treasures that we have collected during the festival. Thus they will truly enrich us; thus we can integrate them into everyday life, which recommences at the end of the seventh day.” 9

But for the last millennium, Shemini Atzeret has also been a day to pray for rain. Israel is a land with parched summers and few year-round rivers, so life depends on winter rains. The famines in the Hebrew Bible are the result of winter droughts. Winter is when fields are green, when barley and wheat grow so they can be harvested in the spring.

Nobody wants the winter rains to begin until we have moved out of the sukkah and back into our watertight homes. Nevertheless, we shake the lulav during Sukkot to evoke the sound of rain. On Shemini Atzeret, our liturgy includes two direct prayers for rain.

1) The second Amidah (standing) prayer begins:

You are powerful forever, God; bringing life to the dead, you are abundant in hoshiya—

hoshiya (הוֹשִׁיעַ) = helping, saving, rescuing. (An infinitive hifil form of the verb yasha.)

From Shemini Atzeret in the autumn to Pesach/Passover in the spring, we add the phrase:

—bringing back the wind and bringing down the rain.

2) On Shemini Atzeret only, this praise of a God who brings rainstorms is preceded in some congregations by a prayer addressing “Af-bri”, and followed by a poem begging God to send us water. The prayer spoken on this day only begins:

Af-Bri is the name of the angel of rain, who thickens and shapes clouds to empty them and to make rain, water to crown the valley with green. May rain not be withheld from us because of our unpaid debts. May the merit of the faithful patriarchs protect those who pray for rain.

Sukkot is a celebration of the final harvest of the year, with gestures that anticipate rain for a new growing season. Shemini Atzeret is a plea for normal winter rain.

Simchat Torah

But that is not the end of our vacation from our usual lives. In the diaspora, a one-day holiday often lasts for two days.10 The second day of Shemini Atzeret has become Simchat Torah (“Rejoicing in the Torah”), an observance not of the agricultural cycle, but of the cycle of Torah readings. Rabbis from the 6th to the 11th century C.E. established the Torah portions for every week of the year, completing the book of Deuteronomy this week. For the last thousand years or so, Jews read the final passage about Moses’ death on the evening of Simchat Torah, then start reading about the creation of the world in the book of Genesis.11

Before we begin reading, we circle the sanctuary seven times, as on Hoshana Rabbah, but without the lulav; the leader holds a Torah scroll. At the start of each circuit, the congregation begins chanting the same verse people chanted on Hoshana Rabbah when they circled the altar of the second temple. When the circuit is complete, everyone sings and dances with the Torah scrolls. The holiday is as joyful as the water-pouring during Sukkot at the temple.

Then unrolling the Torah and reading about the end of Moses’ life in Deuteronomy is only a prelude to the birth of the whole world in Genesis.

How do you return to normal after a vacation? Especially if your vacation is a holy celebration?

I suggest that after the life-and-death solemnity of Yom Kippur, people need the seven (or eight) days of intense festivity called Sukkot. But after Hoshana Rabbah, the Israelites were not emotionally ready to simply go home and go back to work the next day. So they took an extra day, Shemini Atzeret, to hold back from normal life and let the holiness of their proximity to God sink in. Many centuries later, Jews found that this eighth day was not enough; they needed a final celebration to mark the end of an old life and the beginning of a new one. And Simchat Torah fit the bill.

Simchat Torah begins at sunset on October 7, 2023—the 23rd day of the holiday-packed month of Tishrei. Whether we are dancing with the Torah or sitting in our own homes thinking about going back to work, may we step lightly into a new year and a new season, and savor the small joys that ordinary life brings when we are in touch with our inner selves, the natural world, and the people around us.

- Numbers 29:12-34.

- Leviticus 23:39-43.

- A shofar is a natural trumpet made from the horn of a ram or goat. It is blown in the Hebrew Bible to announce certain holy days, or the start of a battle. Talmudic descriptions of the water pouring during Sukkot can be found in Talmud Bavli, Sukkah 48a, 50a, 51a, and 53a. Quotes from tractate Sukkah follow the William Davidson translation in www.sefaria.org.

- Etrogim is the plural of etrog.

- In the Torah reading for Hoshana Rabbah, the seventh day of Sukkot: Numbers 29:29-34.

- Talmud Bavli, Sukkah 45a.

- Leviticus 23:37.

- Talmud Bavli, Sukkah 47a.

- The Hirsch Chumash, Sefer Vayikra Part 2, translated by Daniel Haberman, Feldheim Publishers, Jerusalem, 2000, pp. 820-821.

- “The diaspora” refers to all Jews living outside Israel. When a holiday that lasts one day in Israel is observed for two days in the diaspora, Jews can start the holiday at sunset in their own location even when it is morning in Jerusalem.

- The entire first Torah portion is not read until the following week.