Jews will celebrate the holiday of Purim this Saturday evening. The evening revolves around the megillah, the book of Esther, and we have a wild time with it. We come in costume, often cross-dressing for the night, and drinking is encouraged. When someone reads the megillah out loud, we make loud noises to drown out the name of Haman, the villain, whenever it comes up. Then the Ashkenazic tradition is to perform a purim spiel, a play based on the story in Esther, full of jokes and innuendos and often comic songs. Purim is the merriest holiday in the Jewish calendar.

The book of Esther itself is a fantasy tale revolving around four characters: Esther, a Jew who becomes the queen of Persia through a beauty contest; Achashveirosh, the foolish king of Persia; Haman, his villainous chief advisor who tries to exterminate all the Jews; and Mordecai, Esther’s wise uncle who replaces Haman as the king’s advisor at the end, after Esther gets the king to save the Jews.

Before the king can hold the beauty contest to choose his new queen, his old queen must be disposed of. So the first episode in the book of Esther, and every purim spiel, is the banishment or death of another character: Queen Vashti.

And there is more than one way to play Vashti.

The kings of Persia

And it happened in the days of Achashveirosh—he was the king from India to Ethiopia—127 provinces. In those days, as King Achashveirosh sat on his royal throne that was in the citadel of Shushan, in the third year of his reign, he made a drinking-feast for all his officials and powerful courtiers of Persia and Medea … (Esther 1:1-2)

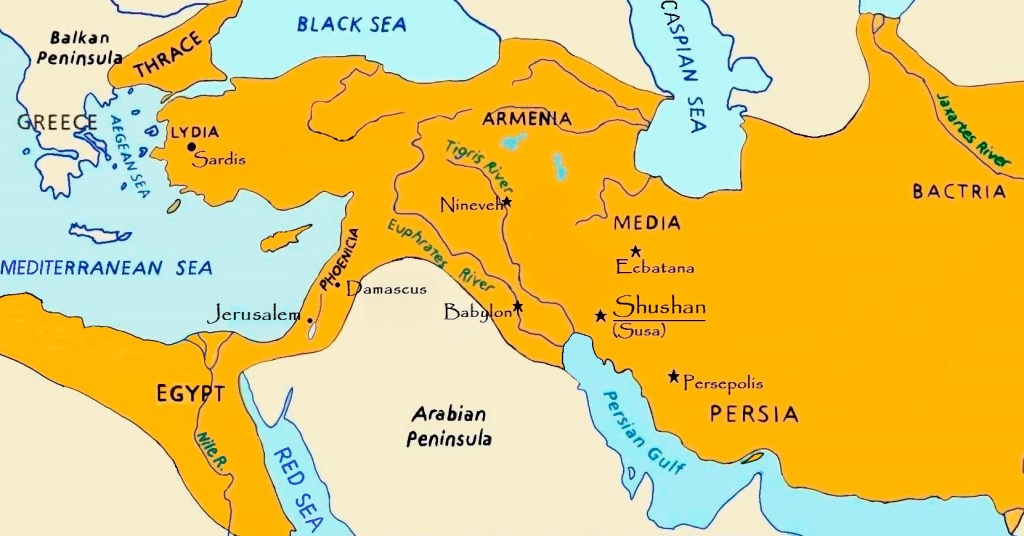

The opening of the book sets a fictional tale in a historical reality. The empire of the Persians and Medes (the Achaemenid Empire) really did stretch from the border of Ethiopian in Africa to the border of India in the east at its height, during the reign of King Darius (522-485 B.C.E.). Cyrus (the founder of the empire), Darius, and his son Artaxerxes (Artachshasteh in Hebrew) all embraced a policy of religious tolerance, according to both history and parts of the books of Ezra and Nehemiah.1

Nehemiah’s King Artaxerxes I, or Artachshasteh, is decisive, thoughtful, and thorough—the opposite of King Achashveirosh in the book of Esther.

The king who gets drunk

Achashveirosh is probably an alternate name for Artaxerxes/Artachshasteh—although unlike Artaxerxes, Achashveirosh is impulsive, vacillating, and stupid. (See my post Esther: Stupid Decisions.)

The book of Esther says that the king’s drinking-feast for the nobles and top officials of the empire lasts for 180 days, while he impresses them with the gorgeous and expensive splendors of his palace. Then King Achashveirosh invites all the men in the city of Shushan to a drinking-feast that lasts for 7 days, in the palace’s impressively bedecked and furnished courtyard. These commoners drink from golden goblets, as much wine as they like.

And the drinking was according to the rule: There is no constraint! Because this was what the king laid down over every steward of his household: to do according to the desire of each man. Also Vashti, the queen, made a drinking-feast for the women in the royal house of King Achashveirosh. On the seventh day, when the king’s heart was tov with wine, he said to … the seven eunuchs who waited on King Achashveirosh, to bring Queen Vashti before the king, in the royal crown, to let the people and the officials see her beauty—for she was tovah of appearance. (Esther 1:8-11)

tov (טוֹב), masculine, and tovah (טוֹבָה), feminine = good; joyful, desirable, usable, lovely, kind, virtuous.

King Achashveirosh’s mind is “joyful” with wine; Queen Vashti is lovely in appearance. The drunk king wants to show off his queen’s beauty.

After all, he has spent 187 days showing off the beautiful treasures of his palace. Perhaps, in his mentally hampered condition, it strikes him that the queen is the most beautiful treasure he owns.

But Esther Rabbah, written in the 12-13th centuries, invents a backstory in which the men at the king’s drinking feast argued about which country had the most beautiful women. One man said that Median women were the prettiest, another that Persian women were. King Achashveirosh declared that his own wife, a Chaldean (i.e. Babylonian) was the most beautiful, and added:

“‘Do you wish to see it?’ They said to him: ‘Yes, provided that she be naked.’ He said to them: ‘Yes, and naked.’” (Esther Rabbah 3)2

Why would the king agree that his own wife should display herself naked? One 21st-century analysis of Esther Rabbah explains: “In this view, Ahasuerus wishes to publicly establish his dominance over Vashti, by forcing the glaring contrast of “queen wearing a crown” and “subservient strumpet.” Such an aggressive act can be understood as stemming from the king’s insecurity, since she is royalty and he is not, for if it was only her beauty that he wished to show off, why was the royal crown necessary? … In other words, Ahasuerus wishes to express with this outlandish demand that Vashti may be royalty but her value to him is only in her beauty.”3

The queen who says no

But Queen Vashti refused to come at the word of the king delivered by the eunuchs. And the king became very angry, and rage was burning within him. (Esther 1:12)

The book of Esther does not say why Vashti refused. But commentators—and purim spielers—have been speculating for centuries.

Rabbis in the Talmud tractate Megillah, written circa 500 C.E., proposed that God suddenly disfigured her, with either a skin disease or a tail, so she was too embarrassed to show herself to men in public.3

In the 11th century, Rashi added that Vashti deserved the skin disease, citing another classic fiction: “Because she would force Jewish girls to disrobe and make them do work on Shabbos, it was decreed upon her to be stripped naked on Shabbos.”4

A century or two later, three rabbis are quoted in Esther Rabbah as suggesting that Vashti was willing to display herself to the men, but only if she were incognito, so she refused to wear her crown. “She sought to enter with only a sash, like a prostitute. But they would not let her.” (Esther Rabbah 3)

Another invention in Esther Rabbah is that Vashti tried to argue with the king before flat-out refusing to appear.

“She sent and said to him things that upset him. She said to him: ‘If they consider me beautiful, they will set their sights on taking advantage of me, and will kill you. If they consider me ugly, you will be demeaned because of me.’” (Esther Rabbah 3)

Vashti’s argument might influence a man who had the wits to think it over, but is useless on a man who is drunk. Then Esther Rabbah reports a second argument:

“She sent and said to him: ‘Weren’t you the stable-master of my father’s house, and you were accustomed to bringing naked prostitutes before you, and now that you have ascended to the throne, you have not abandoned your corruption.’” (Esther Rabbah 3)

It is hardly surprising that in this insult (also invented by the Talmud and Esther Rabbah) does not make King Achashveirosh change his mind, either.

In the 21st century, Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz did not take a position on whether the king wanted his queen to appear clothed or naked. But he pointed out: “Her refusal to obey the command of the king, whose authority was absolutely unlimited, is indicative of her high status. She was unwilling to humiliate herself by parading her body before an audience.”5

In modern purim spiels, when Vashti says no, she often adds a remark about stupid men who treat women like objects and possessions.

Vashti’s fate

In the book of Esther itself, Vashti merely refuses to come, and no explanation is given. Achashveirosh is enraged—maybe because he did not get his way, but more likely to avoid recognizing that he was in the wrong. He asks his seven top advisors:

“According to law, what is to be done with the queen, Vashti, considering that she did not do the command of the king, Achashveirosh, delivered by the eunuchs?” (Esther 1:15)

In the real Persian Empire, the king’s advisors would gently point out these facts:

“Queens do not drink with their male subjects, and thus, in refusing, Vashti is preserving expected power dynamics and behaving as a queen should. And yet, when she insists on her right not to appear before commoners to titillate them, she loses her position.” (Gaines)6

And [his advisor] Memuchan said in front of the king and the officials: “Not against the king alone did Queen Vashti act, but against all the officials and all the peoples in all the provinces of King Achashveirosh. Because the news that goes out about the queen will make all wives treat their husbands with contempt, as they say: King Achashveirosh said to bring Queen Vashti to him, but she would not come.” (Esther 1:16-17)

Memukhan suggests a punishment that would make the women of the empire hesitate before disobeying their husbands.

“If it seems good to the king, let him issue a royal edict, and let it be written into the laws of Persia and Media, so it cannot be passed over, that Vashti must never come before the King Achashveirosh again. And let the king give her royal rank to someone who is hatovah than she.” (Esther 1:19)

hatovah (הַטּוֹבָ֥ה) = (noun) the good; (adjective) better. (A form of tov.)

Apparently there is no Persian law about punishing a queen who disobeys the king, no matter how outrageous the king’s request is. So Memukhan thinks of a reason why Vashti should be punished, and then makes up a punishment for her: losing her rank as queen, and losing her access to the king.

In the 11th century, Rashi interpreted this punishment as requiring Vashti’s execution, so she would be incapable of coming before the king. A century or two later, Esther Rabbah concluded that Memukhan’s proposal in the book of Esther proves the Persian legal system was capricious and inferior to the Jewish legal system. Then it invented three personalreasons why Memukhan had a grudge against Vashti.

But in the book of Esther, we never find out what happens to Vashti. The other six advisors of the king agree with Memuchan, and Achashveirosh, true to form, issues the edict without giving it any thought. Esther Rabbah, elaborating on Rashi’s opinion, adds: “He issued the decree and brought in her head on a platter.”

A 21st-century commentary follows the book of Esther more literally: “Presumably, the text means to communicate that she lived on in the harem—a king’s consort is never afterward free to marry another—but was never allowed to see the king.”7

To make Memukhan’s ad hoc law universal,

He sent scrolls to all the provinces of the king, to each province in its own script and to each people in its own language, that every man should rule his household, speaking the language of his own people. (Esther 1:22)

Rashi explained: “He can compel his wife to learn his language if her native tongue is different.”4

And the Talmud noted that the pettiness of this law turned out to be a good thing: “Since these first letters were the subject of ridicule, people didn’t take the king seriously and did not immediately act upon the directive of the later letters, calling for the Jewish people’s destruction.”3

Esther Rabbah commented on this verse without resorting to fantasy: “Rav Huna said: Aḥashverosh had a warped sensibility. The way of the world is that if a man wishes to eat lentils and his wife wishes to eat peas, can he compel her? No, she will do whatever she wants.”

A replacement queen

After these events, as the rage of King Achashveirosh subsided, he remembered Vashti and what she had done and what had been decreed against her. And the king’s young servants who waited on him said: “They can seek out for the king young virgins of tovot appearance.” (Esther 2:1-2)

tovot (טוֹב֥וֹת) = good, lovely. (Feminine plural of tov.)

In other words, the foolish king remembers his beautiful queen, whom he will never see again, and he feels sad. But his servants remember Memukhan’s advice that Achashveirosh should find another, better queen.

The beauty contest begins. And so does Esther’s story, as she is taken to be a contestant, has her trial night with the king, and wins the queenship.

I want to write a purim spiel in which Esther, waiting in the king’s harem until she is called, meets Vashti, the imprisoned former queen. Vashti would tell Esther all about her last night as queen. Then the two women would suggest increasingly outrageous methods for dealing with a clueless sexist pig. If only I could find the right comic song to go with the dialogue …

- Ezra 1:1-11, 5:5-6:12, and 7:11-26 (but not 4:6-24); Nehemiah 2:1-9 and 5:14.

- Translations of Esther Rabbah are based on The Sefaria Midrash Rabbah, 2022, www.sefaria.org.

- Talmud Bavli, Megillah 12b.

- Rashi (Rabbi Shlomoh Yitzchaki), translation in www.sefaria.org.

- Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz, Introductions to Tanakh: Esther, reprinted in www.sefaria.org.

- Dr. Jason M.H. Gaines, “But Vashti Refused: Consent and Agency in the Book of Esther”, www.thetorah.com/article/but-queen-vashti-refused-consent-and-agency-in-the-book-of-esther.

- Dr. Malka Z. Simkovitch, Dr. Rabbi Zev Farber, Rabbi David D. Steinberg, “Ahasuerus and Vashti: The Story Megillat Esther Does Not Tell You”, https://www.thetorah.com/article/ahasuerus-and-vashti-the-story-megillat-esther-does-not-tell-you.