Before we look at the new concept of God that Yoseif (“Joseph” in English) shares with his brothers in this week’s Torah portion, Vayigash (Genesis/Bereishit 44:18-47:27), let’s look at what the characters in the book of Genesis already believe about God’s ongoing involvement in the universe.1

- God controls the weather, including winds, floods, and storms of hail and sulfur, and wreaks destruction thereby (Genesis 6:13, 7:11, 8:1, 18:21, 19:24-15).

- God blesses some individuals with success and curses some with failure (Genesis 4:14, 4:17, 12:2-324:35, 24:56, 26:28-29).

- God punishes people for certain ethical violations, including: unwarranted murder (Genesis 4:23-24), gratuitous violence (Genesis 6:13), human bloodshed (Genesis 9:6), and raping guests (Genesis 19:4-15).

- God can inflict and heal disease (Genesis 12:17-18, 20:17-18).

- God shares the aversion in the Ancient Near East to a man committing adultery with a married woman (Genesis 12:18-19, 20:1-7). Yoseif assumes that adultery would be “a great wrong before God” in Genesis 39:7-9. (See my post Mikeitz & Vasyeishev: Yoseif’s Theology, Part 1.)

- God gives people significant dreams (Genesis 15:13-16, 20:3, 22:1-3, 26:24, 28:11-16, 31:24, 31:29, 31:42, 32:25-31). Yoseif goes further and claims that dream interpretations also come from God.2

- Only God can “open wombs”, giving childless women children (Genesis 17:16-21, 18:10-15, 21:1-2, 25:21, 29:31. 30:2. 30:22-23).

- Perhaps God can influence the course of history; God makes promises to Avraham, Yitzchak, and Yaakov that their descendants will someday own the land of Canaan (Genesis 12:7, 132:14-17, 15:7, 15:18-21, 17:8, 26:2-3, 28:13, 35:12), but Avraham doubts it will happen (Genesis 15:8 ), and the other two patriarchs are silent on the subject.

- Perhaps God can influence more immediate events; three characters pray to God for specific outcomes (Avraham’s steward in Genesis 23:12-19; Yitzchak (“Isaac”) in Genesis 25:21, 27:28-33, and 28:3-4; and Yaakov (“Jacob”) in Genesis 32:10-13).

Yoseif’s relationship with God

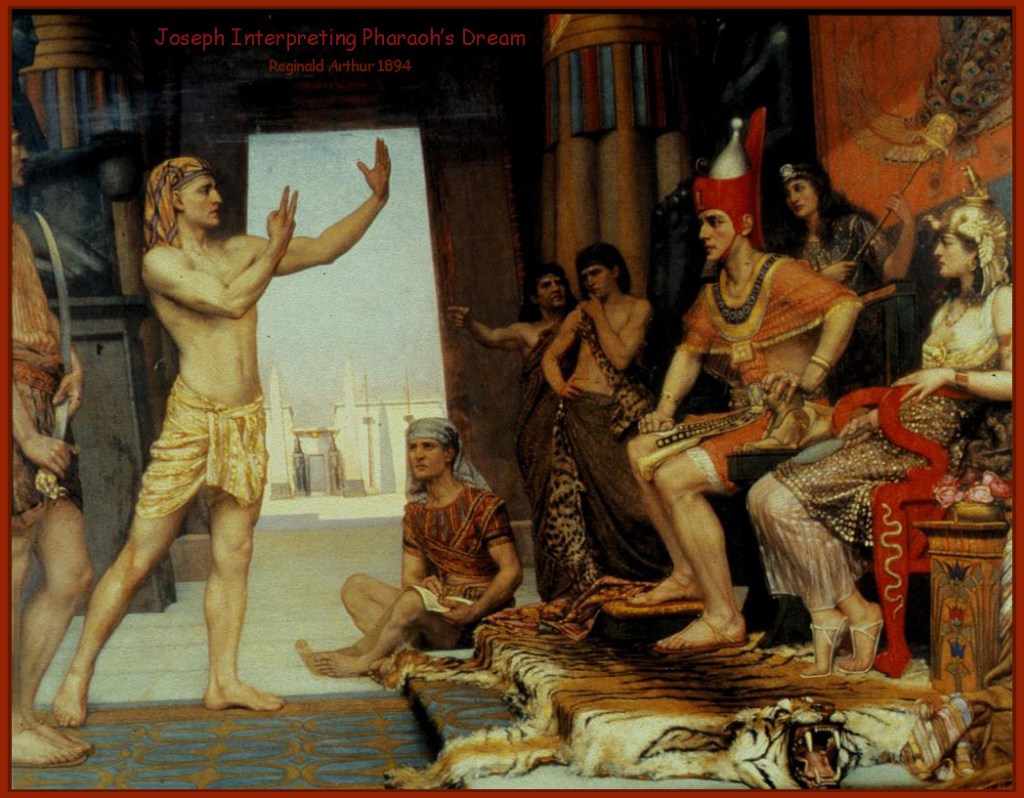

Although God addresses Yoseif in speech, he credits God with giving him the correct interpretations of four dreams: two dreams by imprisoned officials of Pharaoh and two dreams by Pharaoh himself.3 When Yoseif hears these dreams, the interpretation just occurs to him at once. (See my post Mikeitz & Vasyeishev: Yoseif’s Theology, Part 1.)

When he encounters a problem, such as the seven years of plenty followed by seven years of famine that Pharaoh’s dreams foretell, the solution also occurs to him at once—but he does not attribute his solutions to God. He tells Pharoah his solution for getting Egypt through the seven years of famine: appointing “a discerning and wise man” to stockpile grain nationwide during the seven years of plenty. Pharaoh announces:

“Could we find [another] like this man, who has the spirit of an elohim in him?” (Genesis 41:38)

Elohim (אֱלֹהִים) = gods, a god, God.

Although Yoseif has been quick to say that God, not he, interprets dreams, he is silent when Pharaoh says the spirit of God is in him. Pharaoh appoints Yoseif as the administrative head of all Egypt.

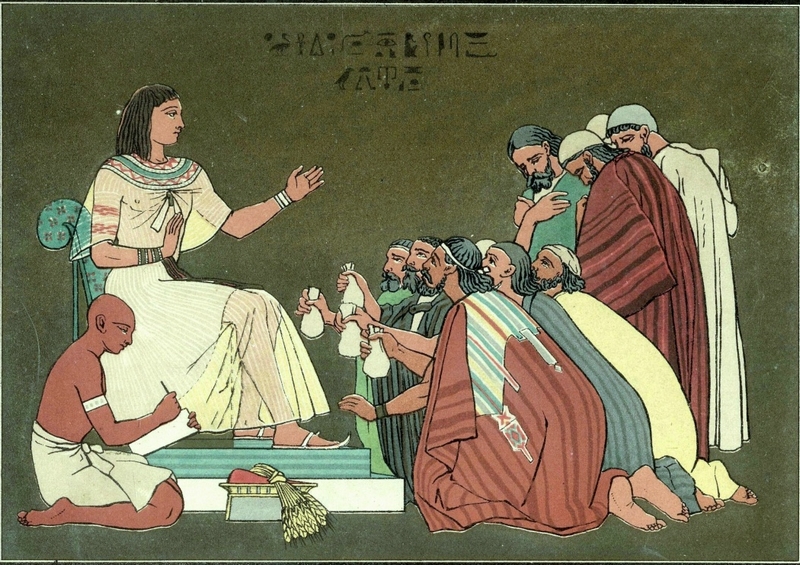

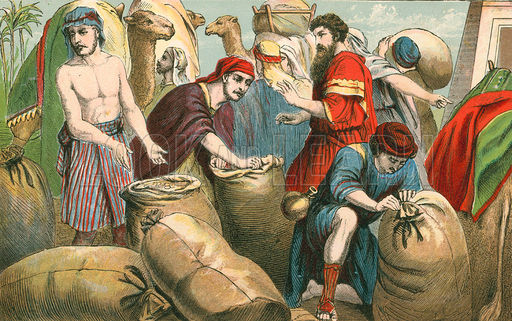

In the first year of famine, Yoseif’s ten older brothers come to Egypt to buy grain. They have not seen him since he was 17, when they threw him in a pit, considered killing him, then sold him as a slave to a caravan bound for Egypt.4 The brothers do not recognize the 38-year-old Egyptian nobleman in front of them, and Yoseif converses with them through an interpreter, pretending he does not know Hebrew.

On the spot, he invents an elaborate scheme for testing whether his older brothers have reformed, and for getting his innocent younger brother, Binyamin (“Benjamin” in English), to Egypt. (See my post Mikeitz: A Fair Test, Part 1.) Yoseif sees nothing unethical in lying to and manipulating his brothers. He cares about being unethical “before God”, and so far, God has not said anything about lying.

A theory about God

In the second year of famine, Yoseif’s brothers return, with Binyamin, in order to buy more grain. And Yoseif continues to test his older brothers. (See my post Mikeitz & Vayigash: A Fair Test, Part 2.) The testing finally ends in this week’s Torah portion, when Yehudah (“Judah” in English) begs Yoseif to enslave him instead of Binyamin.5 Then Yoseif reveals his identity.

And Yoseif said to his brothers: “Come close to me, please!” And they came close. And he said: “I am Yoseif your brother, whom you sold into Egypt. And now, do not be pained, and do not let anger kindle in your eyes that you sold me here. Because to preserve life, Elohim sent me before you.” (Genesis 45:4-5)

After this startling claim, Yoseif explains his view of God’s plan.

“For this is two years the famine has been in the midst of the land, and there are still five years more in which there will be no plowing or harvest. So Elohim sent me ahead of you, to make you she-eirit and for keeping you alive, as a great deliverance. So now, you did not send me here, but Elohim! And [Elohim] has established me as av to Pharaoh and as lord of all his house and as ruler over all the land of Egypt.” (Genesis 45:6-9)

she-eirit (שְׁאֵרִית) = a remnant, remainder, residue. (In this verse, she-airit refers to a group of survivors.)

av (אָב) = father, forefather, male ancestor; chief advisor to a ruler.

Some commentators have written that Yoseif has been figuring this out for a while.6 But I think that Yoseif’s insight is the latest in a long string of sudden inspirations.

Yoseif would not be in a position to rescue his whole family from starvation if it were not for both his brothers’ evil deed, and his own sharp insights. His speech to his brothers might mean that he is now giving God credit for both their assorted levels of wickedness,7 and his own cleverness—in other words, for their respective personalities. In this interpretation, humans have free will to make their own decisions. But God determines who tends to be consumed by jealousy, and who is quick-witted.

According to 21st-century commentator Robert Alter, “Joseph’s … recognition of a providential plan may well be admirable from the viewpoint of monotheistic faith, but there is no reason to assume that Joseph has lost the sense of his own brilliant initiative in all that he has accomplished, and so when he says “God” (‘elohim, which could also suggest something more general like ‘providence’ or ‘fate’), he also means Joseph.”8

On the other hand, Yoseif’s own adolescent dreams about his brothers bowing down to him came true, even though many accidents of fate could have intervened. And his interpretations of the dreams of Pharaoh’s imprisoned officials came true, even though Pharaoh might have changed his mind about whom to pardon and whom to execute. Yoseif might be crediting God not with forming a human’s character, but with manipulating events at key moments by nudging people toward certain decisions and away from others.

According to 21st-century rabbi Jonathan Sacks, God is always nudging people: “One of the core messages of this narrative is just that—to remember that God plays a role in our lives on a daily basis even if we don’t realise it at the time. … One of the main and overarching messages is that God is behind the scenes making sure that events occur and destinations are reached according to His plan.”9

Perhaps the way you interpret Yoseif’s speech depends on your own beliefs about how much power God exercises over human beings—or how much interest God has in making things happen.

Yoseif then tells his brothers:

“Hurry and go up to my father and say to him: ‘Thus says your son Yoseif: Elohim has placed me as lord of all Egypt; come down to me, don’t remain!” (Genesis 45:9)

If God has arranged the past 22 years in order to rescue the whole extended family of his father Yaakov (“Jacob” in English), then it is time to get the patriarch down to Egypt, along with all of the wives and children of Yoseif’s eleven brothers.

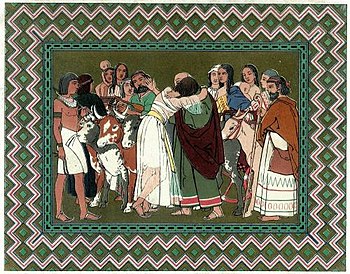

Yoseif promises to provide for them all, and to settle them and their flocks and herds in Goshen, near the capital. Then he embraces Binyamin.

And he kissed all his brothers, a wept upon them. After that his brothers spoke with him. (Genesis 45:15) Why are they silent while Yoseif is explaining his theory that God arranged everything for the long-term good of the family? Maybe they are in shock at the knowledge that Yoseif’s annoying dreams came true: he rules, and they have bowed down to him. Maybe they do not believe his theory about God, but they do not dare annoy him by arguing.

Believing the theory

The famine ends in five years, but the whole family stays in Egypt. After all, Yoseif is still second only to Pharaoh, and his brothers now own land there and have lucrative administrative jobs supervising Pharoah’s flocks.10

The patriarch Yaakov dies after seventeen years in Egypt, and all twelve of his sons accompany his body to Canaan for burial. After they return to Egypt, Yoseif’s older brothers say to one another:

“What if Yoseif holds a grudge, and actually repays us for all the evil that we dealt out to him?” (Genesis 50:15)

They send a message, purportedly from their father, ordering Yoseif to forgive them.

Then his brothers also went, and they prostrated themselves, and said to him: “Here we are, slaves to you!” But Yoseif said to them: “Do not be afraid! For am I in place of Elohim?” (Genesis 50:18-19)

Earlier in Genesis, in the Torah portion Vayeitzei, Yaakov said the same thing to his childless wife, Rachel, several years before she finally became pregnant.

Rachel … said to Yaakov: “Give me children! If not, I will die!” Then Yaakov heated up against Rachel, and he said: “Am I in place of Elohim, who has withheld from you fruit of the belly?” (Genesis 30:1-2)

Yaakov meant that only God could “open her womb”. Now their son Yoseif is asking the same rhetorical question, saying that only God can punish his older brothers.

According to Rashi, Yoseif means: “Even if I wished to do you harm, would I at all be able to do so? For did you not all design evil against me, and you did not succeed because the Holy One, blessed be He, designed it for good. How, then, can I alone, without God’s consent, do evil to you?”10

But Hirsch wrote that even if the decision were up to Yoseif, he would not punish them: “God can judge the thoughts, the intentions. I, as a human being, see only the result, and in that respect I owe you deep gratitude.”11

Yoseif concludes by stating that his brothers’ intentions years ago really were evil; but what matters is that the result was good.

“And you, you planned evil against me; Elohim planned it for good, in order to do as it is this day—to keep many people alive.” (Genesis 50:20)

This time, Yoseif’s older brothers are comforted. They are now certain that Yoseif would never oppose God by punishing them for their long-ago crime.

Is Yoseif’s view of how God operates original? Not quite; there are intimations in earlier Genesis stories that God sometimes answers prayers by making things happen (see #9 above) and that God can promise to eventually give the descendants of the patriarchs the land of Canaan (see #8 above).

But Yoseif changes a vague feeling that God influences events into a definite statement that God controls people enough to determine either their personalities, and/or their actual deeds; and God does this to achieve concrete objectives in history.

How much power does God exercise in human affairs? To what extent do human beings have free will? These are questions that theologians and philosophers have chewed over for centuries.

Many people today believe that a powerful God (preferably omnipotent and omniscient) runs the show, but also that humans are free to make their own decisions and act on them. So, like Yoseif, they resolve the inherent contradiction by positing a God who arranges human destiny behind the scenes—loading the dice to make sure that God’s own goals are met, while granting humans a limited sphere of free will.

Are they right? If so, does God do it by determining our personalities (so we will naturally make the decisions God needs for the long-term plan), or by directing our impulses at the moment of decision?

And if not, what do you believe instead about God and about free will?

- The authors of Genesis also reveal assumptions about God in the narrative, but I do not assume that the characters share these beliefs unless one of them hears or says something to that effect.

- Genesis 40:8, 41:16.

- The title “Pharaoh” in English is Paroh (פַּרֺה) in Hebrew.

- When Yoseif was their teenage nemesis, all ten of his older brothers cooperated in seizing and stripping him. When Reuvein objected against bloodshed, they threw him into a pit. Then Judah talked the others into selling him instead of leaving him to die there. (Genesis 37:19-27)

- Genesis 44:18-34. See my post Vayigash: Compassion.

- E.g. 19th-century rabbi Shimshon Rafael Hirsch, The Hirsch Chumash: Sefer Bereshis, translated by Danield Haberman, Feldheim Publishers, Jerusalem, 2002, pp. 814-815.

- See footnote 4.

- Robert Alter, The Five Books of Moses, W.W. Norton & Co., New York, 2004, p. 261.

- Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks, Covenant & Conversation, “The Angel Who Did Not Know He Was an Angel: Vayeshev 5780”, December 2019.

- Genesis 47:6, 11.

- Rashi (11th-century rabbi Shlomoh Yitzchaki), translation in www.sefaria.org.

- Hirsch, p. 897.