At age 17, Yoseif (“Joseph” in English) is a spoiled brat. He tattles on his ten older brothers, and he tells them two dreams that predict they will all bow down to him someday. His brothers hate him so much that they want to kill him. As soon as they are all far from home, they grab Yoseif, strip off the fancy tunic their father gave him, and throw him into a pit. Then they sell him as a slave to a caravan bound for Egypt.

Vayeishev: Success

No doubt this is a sobering experience for Yoseif; in Egypt he is far more diplomatic. As last week’s Torah portion, Vayeishev (Genesis 37:1-40:23), continues, we learn that Yoseif is also intelligent, and has what a modern person might call good luck. The Torah puts it another way:

And Y-H-V-H was with Yoseif, and he became a successful man … and everything that he did, God made successful in his hand. (Genesis/Bereishit 39:2-3)

Potifar, the Egyptian official who buys him, notices Yoseif ‘s achievements, and makes Yoseif his steward and personal attendant. What Potifar’s wife notices about the young Hebrew man is his exceptional good looks.

And she said: “Lie down with me!” But he refused, and he said to his master’s wife: “Hey, my master … has not withheld anything from me except for you, his wife. Wouldn’t this be a great evil? And I would be doing wrong before Elohim!” /(Genesis 39:7-9)

Elohim (אֱלֹהִים) = gods, a god, God.

This is the first time in the Torah that Yoseif mentions God. He uses a term that could apply to any god, although he would know the name Y-H-V-H, the personal name of the God of his father, Yaakov (“Joseph”). Perhaps Yoseif does not want to reveal that name to a foreigner. Or perhaps he uses a generic term so that Potifar’s wife will know what he is talking about.

Despite Yoseif’s refusal, Potifar’s wife keeps importuning him, and as soon as they happen to be alone in the house, she grabs him. Yoseif flees, leaving his garment in her hands. Spitefully, she accuses him of attacking her, and he is sent to jail.

In the dungeon, God blesses Yoseif with success again, and the prison overseer puts him in charge of all his tasks.

The overseer of the roundhouse did not need to look after anything at all in his hands, because Y-H-V-H was with him [Yoseif], and whatever he did, Y-H-V-H made successful. (Genesis 39:23)

One morning Yoseif asks two of the prisoners, Pharaoh’s chief cup-bearer and Pharaoh’s chief baker, why they are looking especially glum.

And they said: “A dream we have dreamed, and there is no interpreter for it!” And Yoseif said to them: “Aren’t interpretations from Elohim? Recount it, please, to me.” (Genesis 40:8)

All dreams in the Hebrew Bible are considered messages from God. Some dream symbols have obvious interpretations; Yoseif’s brothers had no doubt that his dream of eleven wheat sheaves bowing down to him meant that his eleven brothers would someday bow to him as if he were a king. But more difficult dreams require professional interpreters. Being in jail, Pharaoh’s two officials have no access to professionals.

According to Ramban, Joseph is not claiming either that he is a professional interpreter or that God answers his questions; he is merely saying “If it is obscure to you, tell it to me; perhaps He will be pleased to reveal His secret to me.’”1

The two prisoners tell Yoseif their dreams, which seem like two variations of the same dream.

At this point, we might expect God to speak to Yoseif and tell him what their dreams mean. After all, hearing God speak runs in his family. God spoke to his father, Yaakov, and to his grandfather Lavan, in their dreams.2 And God spoke in the middle of the day to Yoseif’s other grandfather, Yitzchak (“Isaac”), and to his great-grandparents Avraham and Sarah.3

But God never speaks to Yoseif. Instead, dream interpretations occur to him on the spot. He assigns the two dreams of the prisoners different meanings, saying that in three days Pharaoh will pardon the chief cupbearer, but execute the chief baker. That is exactly what happens.

Mikeitz: Pharaoh

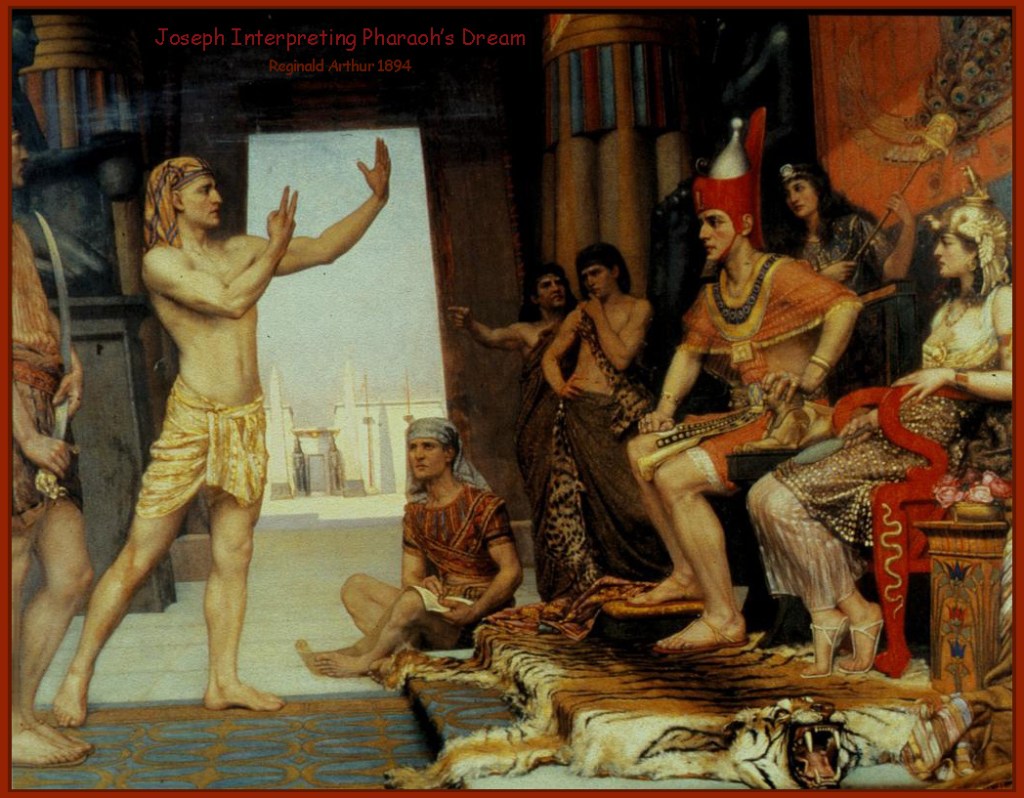

In this week’s Torah portion, Mikeitz (Genesis 41:1-44:17), Pharaoh4 has two dreams. When none of his magicians can interpret the dreams, Pharaoh’s chief cup-bearer speaks up and tells him about the young Hebrew dream interpreter in the prison. At once Pharaoh sends for Yoseif.

And Pharaoh said to Yoseif: “… I have heard about you, saying you [need only] hear a dream to interpret it.” And Yoseif answered Pharaoh, saying: “It is not in me! Elohim will answer, for Pharaoh’s welfare.” (Genesis 41:15-16)

Yoseif is still claiming that only God can interpret a difficult dream. Now he assumes that God will reveal the interpretations of two more dreams to him. He also assumes that the interpretations he gets from God will lead to Pharaoh’s welfare.

Pharaoh tells Yoseif the two dreams. Again the interpretation of Pharaoh’s dreams occurs to Yoseif immediately. He announces:

“What the Elohim will do, he has told Pharaoh.” (Genesis 41:25)

Both dreams, Yoseif explains, are warning Pharaoh that there will be seven years of plenty followed by seven years of “very heavy” famine.

“And about the repetition of the dream to Pharaoh two times: [it means] that the matter is established by the Elohim, and the Elohim is hastening to do it.” (Genesis 41:32)

Although God does not control everything—the prophecies that God dictates to prophets in the Hebrew Bible only predict what will happen to people if they do not change their course of action—God does control the weather.

Next Yoseif unselfconsciously gives Pharaoh some advice.

“And now, may Pharaoh be shown a discerning and wise man, and may he set him over the land of Egypt.” (Genesis 41: 33)

Yoseif goes on to explain how this man must appoint overseers to stockpile grain during the seven good years, and guard the stockpiles as a reserve for the seven years of famine. Since he does not mention God when he tells Pharaoh the wisest course of action, we can assume Yoseif figures it out himself.

And Pharaoh said to his servants: “Could we find [another one] like this man, who has the spirit of an elohim in him?” (Genesis 41:38)

Pharaoh is not saying that Yoseif is possessed, but rather that he receives divine inspiration.

And Pharaoh said to Yoseif: “After an elohim has made you know all this, there is no one who is as discerning and wise as you. You yourself will be over my house! … See, I place you over all the land of Egypt!” (Genesis 41:39-41)

And he gives Yoseif his signet ring. Pharaoh remains the monarch, but Yoseif, at age 30, is now the ruler of Egypt.

Eight years later, after the famine has struck “the whole surface of the earth”,9 Yaakov sends his ten older sons from Canaan to Egypt to buy grain.

And Yoseif’s brothers came, and they bowed down to him, nostrils to the earth. (Genesis 42:6)

They do not recognize Yoseif, who is now shaved and dressed like an Egyptian, and converses with them through an interpreter without revealing that he knows Hebrew. But Yoseif recognizes them. He falsely accuses them of being spies, probably so that they will talk about their family. When Yoseif finds out that Yaakov kept his twelfth and youngest son, Binyamin (“Benjamin”), at home, he instantly hatches a plan to get his little brother down to Egypt. Yoseif and Binyamin are the only sons of Yaakov’s favorite wife, Rachel, and Yoseif may be afraid that his older brothers want to get rid of Binyamin, just as they got rid of him 21 years before.

He imprisons all ten of his older brothers for three days, then tells them that he will keep one of them as a hostage until they return with their youngest brother. At that point he hears their private conversation in Hebrew, in which they agree this must be a punishment (presumably from God) for ignoring Yoseif’s pleas from the pit long ago.5 (See my post Mikeitz: A Fair Test, Part 1.)

A year later, Yaakov finally lets Binyamin go to Egypt with his brothers, because the whole extended family is Canaan is starving. When Yoseif sees the grown man who was a child when Yoseif was sold as a slave, he says:

“Is this your littlest brother, of whom you spoke to me?” And he said: “May Elohim be gracious to you, my son!” (Genesis 43:29)

Yoseif himself plans to be gracious to Binyamin. But he also values God’s blessings.

So far, Yoseif is consistently using the generic term elohim to refer to God. He believes that God controls the weather, and also affects the lives of at least some individuals, including himself. He hopes that God will also improve Binyamin’s life. Yoseif recoils from the thought of committing an offense against God. He believes that dreams come from God, and seems to believe that when he interprets dreams correctly, God is inspiring him. Yoseif’s thoughts about God seem simple, and unlikely to upset anyone.

But in next week’s Torah portion, Vayigash, Yoseif goes out on a theological limb.

- Ramban (13th century Rabbi Moses ben Nachman), translation in www.sefaria.org.

- God speaks in dreams to Yaakov in Genesis 28:12-15 and to Lavan in Genesis 31:24.

- God speaks during the day, directly, to Yitzchak in Genesis 26:2-5 (and at night in 26:24), to Sarah in Genesis 18:15, and to Avraham in Genesis 12:1-3, 12:7, 13:14-17, 15:1-9, 17:1-21, 18:20-33, 21:12-13, and 22:16-18 (and in dreams in Genesis 15:12-29 and 22:1-2).

- The title “Pharaoh” in English is Paroh (פַּרֺה) in Hebrew. The bible uses it for every pharaoh, without an article.

- Genesis 42:21-22.