Every week of the year has its own Torah portion (a reading from the first five books of the Bible) and its own haftarah (an accompanying reading from the books of the prophets). This week the Torah portion is Va-eira (Exodus 6:2-9:35), and the haftarah is Ezekiel 28:25-29:21.

Apparently God really wants Egypt to know who God is. The god of Israel asks the prophet Moses to tell Pharaoh “and you will know that I am God” three times in this week’s Torah portion, Va-eira. And God tells the prophet Ezekiel how God will bring down the Egyptians “and they will know that I am God” four times in this week’s haftarah.

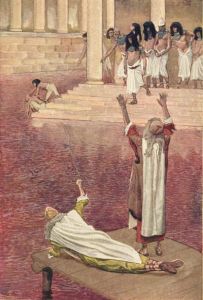

Before God inflicts the first of ten terrible miracles on Egypt, God instructs Moses to meet Pharaoh on the shore of the Nile and warn him that the water will turn into blood.

And you shall say to him: YHVH, the god of the Hebrews, sent me to you to say, ‘Let My people go and they shall serve Me in the wilderness’, but hey—you did not listen before now. Thus says YHVH: ‘By this teida that ani YHVH’. (Exodus 7:16-17)

YHVH = the Tetragrammaton or four-letter personal name of God that Jews consider most sacred. The name appears to be a form of havah or hayah (הוה or היה) the root of the verb “to be”, “to happen”, or “to become”, but it is a form that does not fit any Hebrew verb conjugations.

teida (תֵּדַע) = you will know, experience, be acquainted with, recognize, realize, have intercourse with.

ani (אֲנִי) = I [am].

Pharaoh hardens his heart during the seven days of bloody water, claiming it is not a divine miracle, so he does not experience or recognize the god of Israel.

God’s goal of being known by Pharaoh reappears when Moses talks about the second miracle, the plague of frogs:

… so that teida that there is none like YHVH our god. (Exodus 8:6)

—and again when God tells Moses the fourth plague will be more miraculous, because the swarm will be excluded from the place where the Israelites live,

…so that teida that ani YHVH in the midst of the land. (Exodus 8:18)

It takes ten miracles or plagues before Pharaoh finally knows YHVH, and can no longer harden his heart in denial. The knowledge comes from experiencing what God can do in the world.

The haftarah for this week’s Torah portion is a passage from the book of Ezekiel, set many centuries later during the Babylonian exile after King Nebuchadnezzar conquered the Israelite nation of Judah in 597 BCE. Judah had asked Egypt to help it fight the Babylonians, and Egypt had not come to the rescue. So Ezekiel prophesies that God will restore the land to the Israelites and punish Egypt, and both peoples will “know” God.

…then they will dwell on their soil that I gave to My servant, to Jacob. And they will dwell on it in safety, and they will build houses and plant vineyards, and they will dwell on it in safety when I have passed judgments on all those who despise them from all around; veyad-u that ani YHVH their god. (Ezekiel 28:25-26)

…then they will dwell on their soil that I gave to My servant, to Jacob. And they will dwell on it in safety, and they will build houses and plant vineyards, and they will dwell on it in safety when I have passed judgments on all those who despise them from all around; veyad-u that ani YHVH their god. (Ezekiel 28:25-26)

veyad-u (וְיָדְעוּ) = and they will know, realize, experience, etc. (A form of the same verb as teida.)

The Israelites will once again know YHVH is their god when they have first-hand experience of this amazing reversal in fortune.

The hafatarah continues with a poem describing the future downfall of Egypt. Then Ezekiel says:

Thus said my master, YHVH: Here I am over you, Pharaoh, king of Egypt …To the beasts of the earth and to the birds of the sky I have given you for food. Veyade-u, all the inhabitants of Egypt, that ani YHVH; because you were a walking-stick of reed to the House of Israel; when their hand grasped you, you would break…(Ezekiel 29:3-6)

The implication is that because Egypt failed to support the Israelites, God will make sure all Egyptians know from experience who YHVH is.

And the land of Egypt will become a deserted place and a ruin; veyade-u that ani YHVH, because he [Pharaoh] said: The Nile is mine and I made it. (Ezekiel 29:9)

Egyptians must also realize that although their pharaoh claimed he created the Nile, really YHVH created everything. In order to accomplish this, God will reduce Egypt to the lowest of nations.

And never again will they inspire trust in the House of Israel … veyade-u that ani the lord YHVH. (Ezekiel 29:16)

Therefore, thus says my master YHVH: Here I am, giving the land of Egypt to Nebuchadnezzar, king of Babylon. And he will carry off her wealth and loot her loot and plunder her plunder, and she will be a reward for his army. …On that day… veyade-u that ani YHVH. (Ezekiel 29:19, 29:21)

In all of these cases in Exodus and Ezekiel, people are expected to realize who God is after they have experienced an unexpected disaster or triumph, a miraculous change in fortune. The experience is supposed to be so powerful that both Israelites and Egyptians will realize that only the most powerful god in the world could create such a miracle, and that this supreme god is the god of Israel.

Furthermore, both peoples will know God by the name YHVH, the four-letter name based on the verb “to be”. Is this detail repeatedly included simply because it is the name the Israelites use for their god? Or does it carry another meaning?

In last year’s post on this Torah portion (Va-eira: The Right Name) I suggested that the idea of God as “being” or “becoming” is intellectually appealing, but too abstract for an emotional relationship with God. Now I notice that the phrase “know that I am YHVH” always occurs in the Torah and haftarah portions in the context of knowing God’s power to change fate and to create. What is most important is for the Egyptians and for the defeated and deported Israelites to realize that the god of Israel is the god of existence itself. Nothing can have power over YHVH.

I have experienced no inexplicable miracles or reversals of fortune in my own life. I do not know God in that way. I acknowledge the reality of being, that there is something rather than nothing, and I could call that God, even if it is irrelevant to the anthropomorphic god of the Bible.

But I will not. My unmiraculous life is full of meaning and my soul is full of awe, so “I know”—yadati (יָדַעְתִּי)—that there is something I might as well call God that goes beyond the fact of existence.

Teida that ani YHVH = You will know that I am Being.

Then what, or who, is the “I”?