(This is my eighth post in a series about the conversations between Moses and God, and how their relationship evolves in the book of Exodus/Shemot. If you would like to read one of my posts about this week’s Torah portion, Ki Tisa, you might try: Ki Tisa: Making an Idol Out of Fear.)

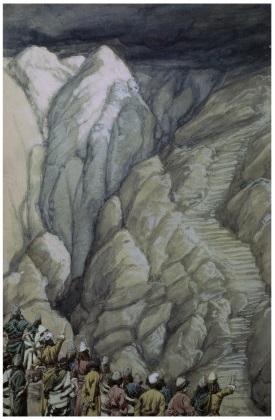

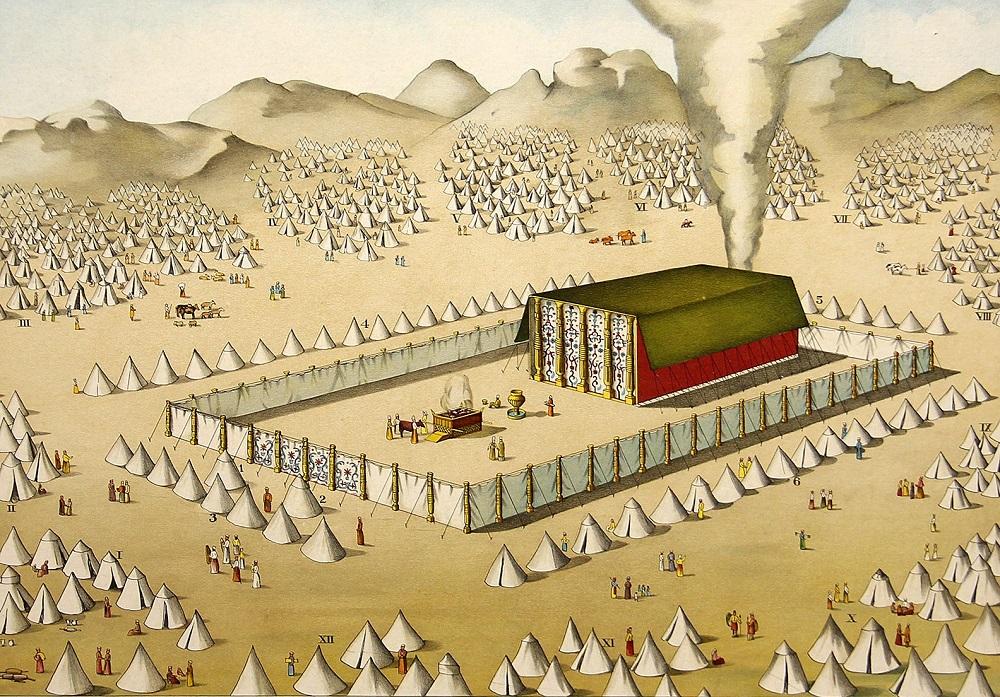

The Israelites reach Mount Sinai three months after they leave Egypt, and perhaps a couple of years after God recruited Moses on that same mountain to serve as their prophet and leader.

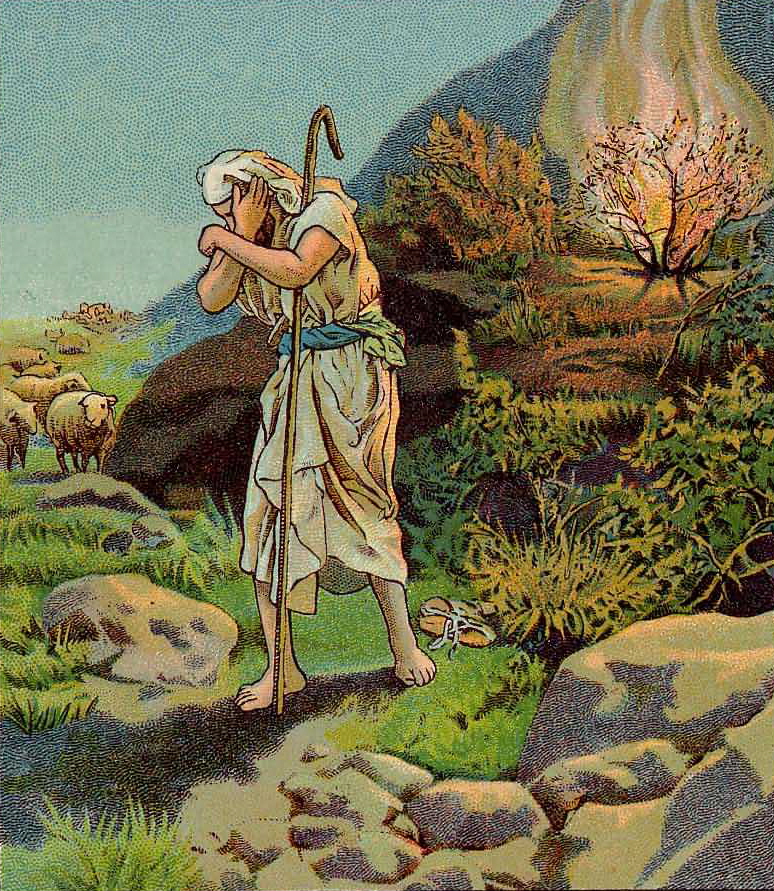

The ultimate goal of the Israelites’ journey is Canaan, which God has promised to give them as their own land (after dispossessing the people who already live there). But Moses knows that Mount Sinai, also called Mount Choreiv or simply “the mountain of God”, is a necessary stop on the way. Back when God first spoke to Moses, out of the fire in the bush that burned but was not consumed, God said:

“When you [singular] have brought the people out of Egypt, you [plural] will serve God at this mountain.” (Exodus 3:12)

Moses does not know that this is the spot where God will stage an impressive revelation, and make a covenant with the Israelites. But after all his leadership training in Egypt and on the road, he is ready for whatever God has in mind. (See my posts Shemot to Bo: Moses Finds His Voice and Beshallach: Moses Graduates.)

Up and down the mountain

… and Israel camped there, opposite the mountain. And Moses went up to God, and God called to him from the mountain, saying: … (Exodus 19:2-3)

Moses takes the initiative and starts climbing up the mountain before God calls to him. According to the 18th-century commentary Or HaChayim,

“Moses felt that if he waited until he would be asked to ascend, this would demonstrate both lethargy on his part and perhaps even unwillingness. … As soon as God noticed that Moses was ascending, God called out to him. You have to remember that it is in the nature of sanctity, not to make the first move towards a person until that person has made active preparations to welcome such sanctity.”1

Yet in Egypt, when Moses first initiated a conversation with God, he did not go to any special place first.2 Moses and God have had conversations in Egypt, at the Reed Sea, and at several spots on the road to Mount Sinai, all without special preparations.

I think Moses follows a different procedure when the Israelites reach Mount Sinai because he knows that something significant will happen there, even though he does not know what. Now that they have arrived, Moses does not wait for God to make the first move. He has learned how to think like a leader. So he decides to show the Israelites that this mountain is God’s place, where something important will happen. So he decides to show the Israelites that this mountain is God’s place by climbing up while everyone watches. Does Moses walk to the spot where he first heard God’s voice? Or does he climb to the summit, closer to the “heavens”? The book of Exodus does not say.

Then God calls to him and says:

“Thus you shall say to the house of Jacob, and you will tell to the children of Israel:3 ‘You yourselves have seen what I did to Egypt, and how I carried you on wings of eagles and I brought you to me. And now, if you really listen to my voice and observe my covenant, you will become to me a segulah out of all the peoples—for all the earth is mine.” (Exodus 19:3-5)

segulah (סְגֻלָּה) = personal treasure, cherished possession.

This is the first time the Torah says God has a segulah. Three later references in the Hebrew Bible say both that the Israelites are God’s segulah and that God “chose” them.4 A standard idea in the Ancient Near East was that each god had his or her own chosen people. The God character in Exodus claims power over all the peoples on earth, but makes the offer of becoming God’s segulah only to the Israelites.

Here God may be using the word segulah to introduce the idea of a covenant or treaty. Being God’s personal treasured possession is conditional upon the people’s behavior: they must earn that status by paying attention to God’s instructions and keeping God’s yet-to-be-revealed covenant with them.

The God character in the Torah definitely plays favorites. Just as God did favors for Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, and Joseph in the book of Genesis, God does favors for Moses in the book of Exodus. So far in this book, God has been patient not only with Moses, but also with the Israelites—even though they keep wanting to go back to Egypt.5

God finishes by saying:

“‘And you, tiheyu to me a kingdom of priests, and a holy nation!’ These are the words that you must speak to the Children of Israel.” (Exodus 19:6)

tiheyu (תִּהְיוּ) = you (plural) will be, will become, would become, should become, must become.

In Exodus 28:1-2, during Moses’ first 40-day stint on top of Mount Sinai, God tells him that Aaron and his sons will be the priests of the new Israelite religion. It is unlikely that God first plans a religion in which everyone (or at least every man) is a priest, and then switches to the hereditary priesthood plan in less than two months. During that period, all the Israelites agree to the covenant with God three times, and do not disobey any of God’s laws.

On the last day of Moses’ 40-day stint, the Israelites commit a major violation by demanding an idol to follow. But Aaron is the one who makes them a golden calf. So God would have no reason to install Aaron and his sons as the priests instead of letting every Israelite be a priest.

Perhaps ‘And you, tiheyu to me a kingdom of priests, and a holy nation!’ is a goal for the distant future, rather than an immediate divine plan. The sentence could be translated: “And you, you should become to me a kingdom of priests, and a holy nation.”

Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks wrote that God’s pronouncement means:

“The Israelites were called on to be a nation of servant-leaders. They were the people called on, by virtue of the covenant, to accept responsibility not only for themselves and their families, but for the moral-spiritual state of the nation as a whole.”6

One of the duties of the priests, we learn in Leviticus 10:10-11, is to teach the people about God’s rules. In a kingdom of priests, presumably, everyone would remind everyone else about the right thing to do.

Up and down again

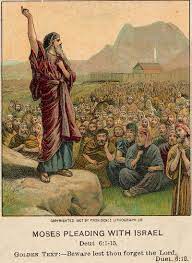

And Moses came and summoned the elders of the people, and he set before them all these words that God had commanded him. And all the people answered as one, and they said: “Everything that God has spoken, we will do!” Then Moses brought the words of the people back to God. (Exodus 19:7-8)

The implication is that Moses climbed back to the top of the mountain to give God the people’s reply. Rashi repeated a common objection in the classic commentary when he wrote:

“But was it really necessary for Moses to deliver the reply to God? God is Omniscient! — But the explanation is that Scripture intends to teach you good manners from the example of Moses …”7

Although later theologians decided that God is omniscient, the God character in the Torah does not know ahead of time what human beings will do.8 This God also loses track of what the Israelites are doing; they suffer because of forced corvée labor for many years before God hears their moaning and recruits Moses to lead them out of Egypt.9 Moses knows how long it took for God to notice the cries of the Israelites. Perhaps now he reports the Israelites’ reply in case God missed it in a moment of distraction.

Moses might also think that climbing Mount Sinai again is more likely to get God’s attention than standing at the bottom and silently praying.

When Moses reaches the top of the mountain again, God speaks first.

And God said to Moses: “Hey, I myself am coming to you in a dark cloud, so that the people will listen when I speak with you, and also they will trust you forever.” Then Moses told the words of the people to God. (Exodus 19:9)

Rabbi Rami Shapiro explained:

“God isn’t saying that He will speak directly to the people that they may know He is God, He is saying that He wants the people to see that He is speaking to Moses so that they will believe that when Moses says such and such is the word of God, they will trust him. There is no reason to think that the people will even overhear what God is saying to Moses; all they will hear is that something is being spoken. Which is exactly what happens …”10

After Moses has reported how the people promised to do everything God said, God gives Moses orders to prepare the Israelites for a revelation (including a dark cloud) in three days. God tells him to make the people holy (without describing the method), to have everyone wash their clothes, to set a boundary around the mountain, and to warn the people that anyone who crosses that line, or even touches it, will be put to death.

Then Moses went down from the mountain to the people, and he made the people holy, and they washed their clothes. And he said to the people: “Be ready for the third day. Don’t go near a woman!” (Exodus 19:14-15)

Once again, Moses is taking initiative. Why does he add this injunction?

According to Leviticus 15:16-18, an emission of semen makes a man ritually impure, and anything it touches also becomes impure. If a man and a woman have sex, they must both bathe and wait until evening before they are ritually pure and able to participate in religious rites. Someone can be ritually pure without being holy, i.e. set aside for God, but a person cannot be holy without being ritually pure.

In a patriarchal society, Moses is addressing only the (heterosexual) men. He orders them to go without sex for two days before the day of God’s revelation. The classic commentators assumed that Moses somehow already knew the laws about ritual purity that God gave later, in Leviticus, and they explained that Moses thought a man’s semen might stay alive inside his wife for three days.11

This seems far-fetched. I prefer Rabbi Steinsaltz’s explanation that Moses was telling the men: “Refrain from sexual relations during these three days in order to focus your minds and prepare for the encounter.”12

At Mount Sinai, God is the boss, and Moses is the middle manager who relays God’s words to the people and the people’s words to God. But God is not a micro-manager, and welcomes it when Moses takes the initiative—as he does when he climbs the mountain to speak with God, and when he adds the order to refrain from sexual intercourse for three days.

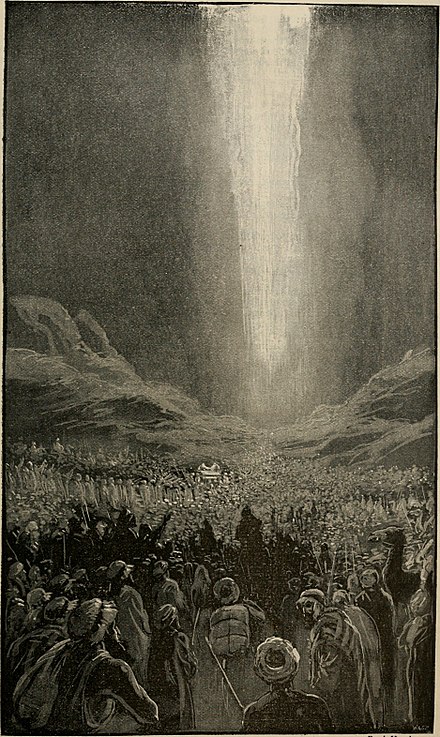

And it happened on the third day, when it became morning. And there were thunder-sounds and lightning-flashes, and a heavy cloud on the mountain, and a very loud sound of a shofar [ram’s horn], and all the people who were in the camp trembled. (Exodus 19:16)

The revelation of God has begun.

To be continued …

- Or HaChayim, by Chayim ibn Attar, translation in www.sefaria.org.

- In Exodus 5:22-23, after his first audience with the new pharaoh, when the Israelites were given more labor instead of the holiday that Moses and Aaron had requested. See my post: Shemot to Bo: Moses Finds His Voice.

- The ethnic group known to the Egyptians in the book of Exodus as Hebrews is usually called the “children of Israel” (i.e. Israelites) in the Hebrew Bible, but occasionally called the “house of Jacob”. Exodus 1:1-6 explains that these people are the descendants of Jacob in the book of Genesis, to whom God gave a second name, Israel.

- Deuteronomy 7:6 and 14:2, and Psalm 135:4, announce both that the Israelites are God’s segulah and that God chose them, using the verb bahar (בָהַר) = “chose” or “chosen”.

- So far, they complain about leaving Egypt and/or say they want to return there in Exodus 14:11-12, 16:3, and 17:3. Their backsliding will continue.

- Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks, Covenant & Conversation, “A Nation of Leaders: Yitro 5781”, 2022.

- Rashi (11th century Rabbi Shlomo ben Yitzchak), translation in www.sefaria.org.

- But God does predict what the pharaoh in Exodus will do, and hardens the pharaoh’s heart at key points to make sure it happens.

- Exodus 2:23-25.

- Rabbi Rami Shapiro, teaching@topica.email-publisher.com, May 25, 2004, Shavuot.

- E.g. Avot deRabbi Natan, Talmud Bavli Niddah 42a and Shabbat 86a, Rashi.

- Rabbi Adin Even-Israel Steinsaltz, The Steinsaltz Tanakh, Koren Publishers, Jerusalem, 2019, quoted in www.sefaria.org.