The covenant between the people of Israel and the God of the Torah has often been compared to a wedding, perhaps ever since the prophecy of the 6th century BCE: As the bridegroom rejoices over the bride, so shall your God rejoice over you. (Isaiah 62:5) According to the Torah, God and the Israelites make their covenant (a contract like a marriage) at Mount Sinai. The Talmud tractate Kiddushin states that the three elements of a wedding are money (the dowry), a written contract (the ketubah), and intercourse. So far in the book of Exodus/Shemot, God has given the Israelites a dowry: their freedom from Egypt, plus the gold and silver that the Egyptians handed over to the Israelites in response to God’s miraculous plagues. In this week’s Torah portion, Ki Tissa (“When you lift”), when Moses comes down from a 40-day meeting with God on Mount Sinai, he brings the other two elements of the wedding: a marriage contract engraved on two stone tablets (presumably the Ten Commandments), and instructions for building a sanctuary so God will “dwell among them”.

Alas, while Moses was away, the bride was unfaithful. The Israelites, terrified that Moses would never return, got Aaron to make a golden calf to lead them. Moses returns to find the people cavorting in front of an idol. Clearly, the Israelites do not yet have enough faith and fortitude for this marriage. So Moses quickly smashes the two stone tablets of the contract, and postpones the building of the sanctuary for cohabitation.

Before the wedding can resume, the bride must have a change of heart. So God and Moses arrange for the Israelites to see their separation from God’s presence.

And Moses, he shall take the tent and pitch it for himself outside the camp, far away from the camp, and he shall call it the Tent of Meeting. Then it will be that anyone seeking God must go to the Tent of Meeting, which will be outside the camp. (Exodus/Shemot 33:7)

In the next two books of the Torah, we learn that anyone who contracts the skin disease tzara-at is ritually impure, and must live outside the camp until he or she is cured. Here in the portion Ki Tissa, the whole camp is ritually impure after the golden calf worship, unfit for worshiping God. Therefore the place where God can be encountered must be far away from the camp—until the whole camp is cured. Only then does the Tent of Meeting move from outside the camp to inside the new sanctuary in the heart of the camp.

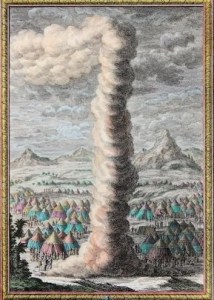

During the period when God does not dwell in the camp, any individual who wants to communicate with God must go to the Tent of Meeting, which will be outside the camp. The Torah does not say whether Moses acts as an intermediary, or God answers the seekers who walk out to the Tent of Meeting directly. But the Torah does describe the experience of the people who wait in the camp while Moses goes to meet God.

Then it was, that when Moses was going out to the Tent, all the people stood up, and each one stationed himself at the petach of his tent, and they gazed after Moses until he came to the Tent. And it was, that when Moses came to the Tent, the pillar of the cloud descended, and it stood at the petach of the Tent, and It spoke with Moses. And all the people saw the pillar of the cloud standing at the petach of the Tent, and all the people stood, and each one prostrated himself at the petach of his [own] tent. (Exodus 33:8-10)

petach = opening, entrance, doorway

How do the people feel when they gaze after Moses, and see him speaking with the pillar of cloud ? How do they feel, knowing that they have jilted God?

The Talmud offers two different theories. In one, the people resent Moses so much, they accuse him of profiting at their expense. In the other, they admire Moses for his confidence that God will speak to him. Either way, they are painfully aware that Moses’ relationship with God is unbroken, while they are suffering through a separation. I think that their jealousy of Moses contains more longing than resentment, since they stand up respectfully when he leaves for the Tent of Meeting, and they prostrate themselves, bowing to God, when they see the pillar of cloud. These are the Israelites who survived the killings Moses and God carried out after the Golden Calf worship, presumably the ones who did not incite idol worship, but did look the other way. Now, after the death of their neighbors and the separation of God’s presence from the camp, the survivors are humble.

The repetition of the Hebrew word petach indicates to me that this period between the destruction of the golden calf and the building of the sanctuary is is a time of openings and doorways. When Moses speaks with God at the entrance of the tent outside the camp, each Israelite stands alone in the entrance of his (and perhaps her) own tent. Each one longs for God from a distance. I can imagine an Israelite bowing down toward the distant God that he or she betrayed. A person’s tent is his dwelling-place, like his body, or his mind. Bowing to God leaves the doorway open; it makes an opening for change.

I have been feeling distant from God lately. I try to pray, since my prayers of gratitude used to make an opening for joy to enter my own “tent”. But these days, the prayers feel formulaic. I am not aware of doing anything to jilt God, but nevertheless I feel a separation. I wish I could see a Moses going out to the Tent of Meeting. Maybe the sight would inspire me. Or maybe then I’d know where to seek God.

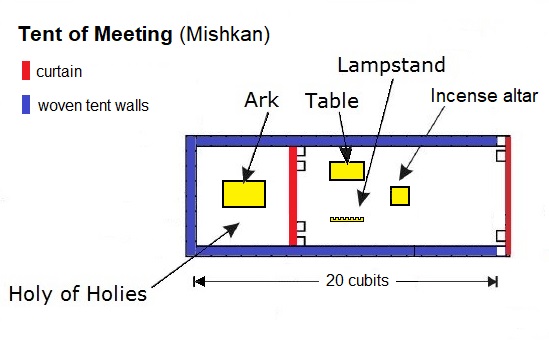

The book of Exodus ends when the people have made everything to build a mishkan, a dwelling-place, for God, and Moses puts all the pieces together. Then God comes into the camp and dwells in their midst. In other words, the wedding resumes, and the covenant is cut or signed between the Israelites and God. Will something similar happen to each of us today, when we yearn for God? Will our longing make an opening? If we work hard to make God’s dwelling-place, will God become manifest to us?

And can we do it individually? Or do we need a whole community, a whole camp, to bring God into our midst?