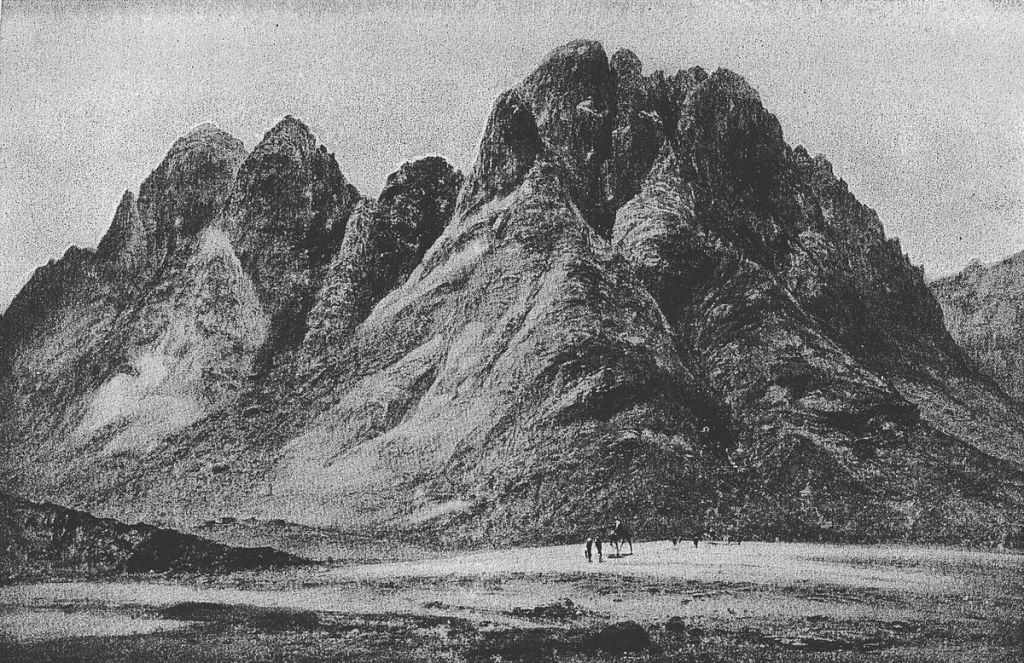

Moses, the Israelites, and some menials who joined them in the exodus from Egypt , are camping in the wilderness of Sinai when visitors arrive at the beginning of this week’s Torah portion, Yitro.

And Yitro, priest of Midian, father-in-law of Moses, heard all that God had done for Moses and for his people, Israel: that God had brought Israel out from Egypt. So Yitro, father-in-law of Moses, took Tzipporah, wife of Moses, after shilucheyha, and her two sons … (Exodus/Shemot 18:1-3)

shilucheyha (שִׁלּוּחֶיהָ) = she had been sent: sent away, dismissed, or divorced. (A pual form of the root verb shalach (שָׁלַח) = send, let go.)

After Moses received orders from God at the burning bush, he took his wife and sons on the first leg of his journey back to Egypt. They spent the night at a lodging place where God came to kill Moses, and Tzipporah saved his life by circumcising one of their sons and smearing the blood on her husband, calling him a “bridegroom of blood”.1 (See my post Va-eira & Shemot: Uncircumcised, Part 2.)

Tzipporah’s decisive action indicates she would be a good person to have by his side in a dangerous situation.2 Yet something about that dramatic ritual made Moses change his mind about bringing his wife to Egypt. Maybe he did not even believe her account of what happened while he was unconscious. So he sent Tzipporah back to her father’s house after she saved his life, and before he met his brother Aaron on the road.3

Was it merely a separation, or a divorce? Was he protecting or rejecting her?

Sending away versus casting out

The pual form4 of the verb shalach appears only 15 times in the Hebrew Bible, usually referring to when a man was sent somewhere. The only other occurrence of this verb in reference to a woman is in second Isaiah:

Where is this scroll of divorce

Of your mother, whom I shilucheyha? (Isaiah 50:1)

Deuteronomy uses the related piel verb form shillach in three laws about sending away wives.

If a man wants a female war captive, he must take her home and let her mourn unmolested for one month before he takes her as a wife. “Then if you no longer want her, veshillachtah her soul, and you must certainly not sell her for silver; you must not treat her brutally, since you overpowered her.” (Deuteronomy 21:14)

veshillachtah (וְשִׁלַּחְתָּה) = then you must set her free, let her go.

If a man tries to return his bride the next morning by claiming falsely that she was not a virgin, “… then she will be his wife; he will not be able to shallechah all his days.” (Deuteronomy 22:19)

shallechah (שַׁלְּחָהּ) = send her away.

And if a man rapes a virgin who is not engaged, he must pay her father and accept her as his wife. “… since he overpowered her, he will not be able to shallechah all his days.” (Deuteronomy 22:29)

In all three of these laws, the verb shillach is used to mean divorce.

Separating

Nowhere else in the Hebrew Bible does a man send his own wife back to her father’s house temporarily, without divorcing her. Yet most commentary before the 20th century assumed Moses did this, either so that Tzipporah and their children would not suffer,5 or so that he could “devote himself entirely to the fulfillment of his mission”.6

One piece of evidence for this interpretation is that when Yitro brings Tzipporah back to Moses, she is still called eishet Moshe (אֵשֶׁת מֺשֶׁה) = wife of Moses, and Yitro is still called chotein Moshe (חֺתֵן מֺשֶׁה) = father-in-law of Moses.

The Hebrew Bible uses only two types of words for divorce: variants of shillach (שִׁלַּח) = send away, set free, let go; and variants of goreish (גֺּרֵשׁ) = cast out, driven out. In other biblical books a divorcee is called a gerushah (גְרוּשָׁה), a female who has been cast out.7 But Tzipporah is not called a gerushah. Moses did not “cast out” Tzipporah; he “sent her away”.

Divorcing

And Moses went out to invite his father-in-law, and he bowed down to him, and he kissed him, and they inquired about one another’s welfare, and they came into the tent. (Exodus 18:7)

Moses greets Yitro warmly, but he does not even acknowledge the presence of Tzipporah and their two sons. Although there are no instances in the Hebrew Bible of a man kissing his wife or ex-wife in public, men do kiss their kinsmen in front of other people.8 Yet the Torah does not say Moses greets his own sons in any way. He does not even perform the basic courtesy of inviting them to dismount and rest.

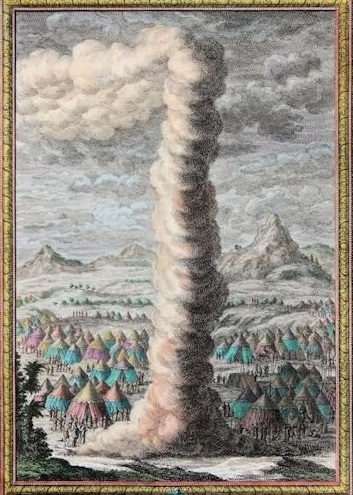

Inside the tent, Moses tells his father-in-law the details of God’s miracles in Egypt and afterward. Yitro makes a burnt offering to Moses’ God, and feasts with Moses, Aaron, and the elders of Israel. No provision for Tzipporah, Gershom, or Eliezer is mentioned. The next day, Yitro gives Moses advice on how to delegate the legal cases his people bring to him.

And Moses sent off his father-in-law, and he went to his own land. (Exodus 18:27)

Do Tzipporah, Geirshom, and Eliezer go home again with Yitro, ignored and rejected? Or do they stay with Moses and the Israelites, ignored and rejected?

The Kushite wife

The name “Tzipporah” never appears again in the Hebrew Bible. A wife of Moses is mentioned only once more, when Miriam and Aaron complain about Moses “on account of the Kushite wife that he took; for he had taken a Kushite wife”. (Numbers/Bemidbar 12:1) Elsewhere in the bible, a Kushite is a dark-skinned person from Kush, which may be either Nubia (south of Egypt) or part of southern Midianite territory (near the Gulf of Aqaba). The commentary is divided on whether this wife is Tzipporah or another woman. One tradition is that Miriam and Aaron complain because Moses is denying his wife sexual relations.9

Certainly Moses does not share his tent with a wife. His tent becomes the Tent of Meeting (with God), and only Moses and his apprentice Joshua sleep there.

Moses’ sons, Geirshom and Eliezer, have no role in the rest of the story of Moses’ life. Joshua inherits Moses’ position as political leader of the Israelites, and Aaron’s son Elazar becomes the high priest. Geirshom and Eliezer are not mentioned again until the first book of Chronicles, which includes them in genealogical lists of Levites in charge of the temple treasuries.10

So I believe that Yitro does leave his daughter and grandsons behind when he says farewell to Moses and goes home. Moses lets Tzipporah and their two sons travel with the Israelites, but he has little or no contact with his erstwhile family. Although they travel with the Israelites, perhaps pitching their tent with the other foreigners on the edges of the camps, Moses maintains his separation from them.

And I think that when Miriam and Aaron speak against Moses “on account of his Kushite wife” in the book of Numbers, they are referring to his neglect of Tzipporah. (I plan to explore this idea further when we reach Beha-alotkha in the Jewish cycle of Torah portions at the end of May 2018).

After Moses separates from Tzipporah on the road to Egypt, we never see him interacting with a wife or child again. If he is married to anyone, he is married to God. If he has any children, they are the thousands of children of Israel that he has become responsible for. He misses out on the long companionship of marriage partners.

So does Tzipporah. Her heroic act in the bridegroom of blood scene is ignored, forgotten. She is treated like excess baggage, passed back and forth between Yitro and Moses. Her name means “bird”, but she is never allowed to fly.

May we have compassion for all caged birds—and for all great leaders.

- Exodus 4:24-26.

- Pamela Tarkin Reis, Reading the Lines, Hendrickson Publishers, Peabody, MA, 2002, pp. 101-102.

- Rashi (11th-century Rabbi Shlomo Yitzchaki) follows the Mekhilta by adding dialogue in which Aaron advises Moses not to bring his wife and sons into Egypt. But the Torah says only that Aaron met Moses at the mountain of God and kissed him; Moses told Aaron what God wanted them to do; and the two brothers went into Egypt and assembled the elders of Israel. There is no mention of Tzipporah or Moses’ sons. (Exodus 4:27-29)

- The pual stem of a verb is passive form of the piel stem, which is usually an intensive.

- Rashi, based on the Mekhilta.

- Samson Raphael Hirsch (19th-century rabbi), The Hirsch Chumash: SeferShemos, translated by Daniel Haberman, Feldheim Publishers, Jerusalem, 2005, p. 301.

- Leviticus 21:7, 21:14, 22:13; Numbers 30:10.

- Jacob kisses his cousin Rachel in front of strangers when he first meets her at the well in Genesis 29:2, 29:10-12. Lavan kisses his daughters and grandsons farewell in front of his men and Jacob’s servants in Genesis 32:1. Esau and Jacob, long-lost brothers, kiss and embrace in front of Esau’s 400 men and Jacob’s retinue in Genesis 33:4.

- Including Exodus Rabbah 46:3, Deuteronomy Rabbah 11:10, Midrash Tachuma Tzav 13, Rashi (11th-century rabbi Shlomo Yitchaki).

- 1 Chronicles 23:15-17 and 26:24-25.