(This is my seventh post in a series about the conversations between Moses and God, and how their relationship evolves in the book of Exodus/Shemot. If you would like to read one of my posts about this week’s Torah portion, Tetzaveh, you might try: Tetzaveh: Flower on the Forehead.)

The first time Moses and God have a conversation on Mount Sinai, God tells Moses to return to Egypt, ask the pharaoh to let the Israelites leave, and persuade the Israelites to follow him out of the country. Moses keeps making excuses to get out of this terrifying mission, certain that he cannot persuade anyone of anything. But God gives him one reassurance after another, finally promising to deploy Moses’ long-lost brother, Aaron, as his spokesman (or perhaps interpreter; see my post: Shemot: Not a Man of Words). Then Moses finally, reluctantly, heads back to Egypt.

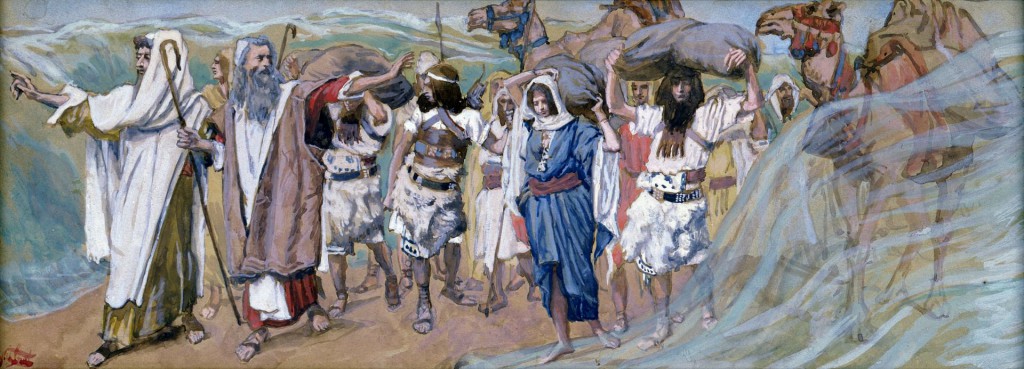

When he leaves Egypt a year or two later, 600,000 Israelites and supporters follow him into the wilderness.1 Although leadership comes more naturally to extraverts, introverts like Moses can become effective leaders with sufficient preparation and self-confidence. As God backs him up in his negotiations with the pharaoh, Moses earns respect from the pharaoh and his court, and his self-confidence increases exponentially.2 His standing also improves with the Israelites; by the time they leave Egypt, the people view both Moses and God (as manifested in a column of cloud and fire) as their leaders.

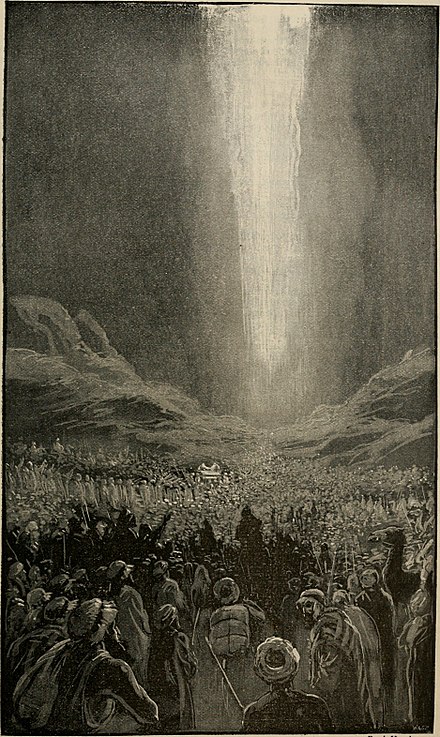

And God was going before them, by day in a column of cloud to lead them on the way, and by night in a column of fire to give light to them for walking day and night. (Exodus 13:21)

A junior leader when the sea splits

The pharaoh has another change of heart, thanks to some heart-hardening from God, and he pursues the Israelites with a squadron of charioteers. God tells Moses to make the Israelites turn around and camp on the shore of the Reed Sea3 so they will appear to be trapped between the Egyptian army and the water. Moses does, even though God neglects to explain the next part of the divine scheme.

And Pharaoh approached, and the Israelites raised their eyes, and hey! Egyptians were setting out after them! They were very afraid. And the Israelites cried out to God. And they said to Moses: “Is it because there are no graves in Egypt, that you took us out to die in the wilderness? What is this you have done to us, to bring us out from Egypt?” (Exodus 14:10-11)

Out of their two leaders, the Israelites address God first, but they blame Moses. The 14th-century commentary Tur HaArokh explained: “When they noted that their prayer had not helped, they became heretical in their attitude, making above-mentioned sarcastic comments to Moses, blaming him for their present predicament.”4

They declare that they were better off being enslaved in Egypt. Moses replies, on his own initiative, that God will do battle for them. But then God tells Moses to order the Israelites to march forward into the sea, adding:

“And you, raise your staff and stretch out your hand over the sea and split it! And the Israelites will come into the middle of the sea on the dry land. And I, I will be here strengthening the Egyptians’ heart, and they will come in after them. Then ikavdah by Pharaoh and by all Pharaoh’s army, by his charioteers and by his horsemen. Then Egypt will know that I am Y-H-V-H …” (Exodus14:16-18)

ikavdah (אִכָּבְדָה) = I will be considered impressive, I will be honored, I will be respected. (From the same root as koved, כֱֺבֶד = weight.)

It is important to God to acquire an impressive reputation in Egypt.5ֶ But it is also important for the Israelites to respect Moses, so God has him initiate the miracle of the parting of the Reed Sea with a dramatic gesture.

The Egyptian charioteers urge the horses onto the dry sea-bed, still chasing the Israelites. But as soon as all the people and their livestock have reached the other side, God lets the water rush back and drown the Egyptians.

And Israel saw the great hand [power] that Y-H-V-H had used against the Egyptians, and the people feared Y-H-V-H, and they had faith in Y-H-V-H and in [God’s] servant Moses. (Exodus 14:31)

In their first conversation on Mount Sinai, God was like a patient parent reassuring an anxious young child. (See my post: Shemot: Moses Gives Up.) In Egypt, God is like a reliable parent to an adolescent uneasy with his place in the world. (See my post: Shemot to Bo: Moses Finds His Voice.) But as the Israelites journey from Egypt to Mount Sinai, God is like a mentor who takes time to make sure a young adult protégé comes to be viewed as a leader And Moses responds by turning to God when he needs advice.

A moment of panic

At Refidim, the Israelites’ last stop on the Sinai Peninsula before Mount Sinai, there is no water. The people are probably carrying some water from the last campsite, but they are anxious—or inclined to grumble.

And the people complained against Moses, and they said: “Give us water, so we may drink!” And Moses said to them: “Why do you complain against me? Why do you test God?” (Exodus 17:2)

Moses has identified so completely with his role as God’s agent that he now considers any quarrel with him a quarrel with God. After all, God makes the decisions; he merely carries them out.

But the people were thirsty for water there, and the people grumbled against Moses, and said: “Why this? To bring us up from Egypt [only] to bring death to me and my children and my livestock by thirst?” And Moses cried out to God, saying: “What can I do to this people? A little more and they will stone me!” (Exodus 17:3-4)

Moses is still insecure about his new role, afraid that at any time the people will turn angry enough to kill him.

And God said to Moses: “Pass before the people, and take with you some of Israel’s elders, and take the staff with which you struck the Nile in your hand, and go.” (Exodus 17:5)

Robert Alter noted: “… passing before the enraged people would be rather like running the gauntlet, and it is this that God compels him to do as the prelude to the demonstration of divine saving power.”6

In this way God nudges Moses to do something courageous. When he does pass in front of the people, they see that he is going somewhere (with witnesses) to find water, and trust him enough to wait for his return.

Calmly God tells Moses the next step:

“Here, I will be standing before you there on the rock at Choreiv. And you must hit the rock, and water with come out of it, and the people will drink.” And Moses did thus, before the eyes of the elders of Israel. (Exodus 17:6)

Choreiv (חֺרֵב) = the alternate name for Mount Sinai, the name used for the “Mountain of God” in the passage about Moses seeing the bush that burned but was not consumed.7 (Ironically, from the root verb charav, חָרַב = dried up, made desolate.)

The Torah does not say that anyone actually sees God standing on a rock at the mountain. Perhaps Moses has developed a sense for the direction from which God’s instructions reach him. The 14th-century commentary Tur HaArokh suggested that Moses saw a vision of an angel on the rock.

And why does God create the miracle at Choreiv instead of at their camp at Refidim? Hirsch speculated in the 19th century that God had planned for water to gush from a rock when they arrived at the mountain, but the Israelites complained about thirst prematurely, before their portable supplies had run out. “The only effect of their untimely murmuring was that even now, while they were in Refidim, God provided them with water from Chorev. The words … seem to indicate that the water flowed from Chorev to the people’s camp in Refidim.”8

A staff initiative

Moses demonstrates his new ability as a leader in one more event before the Israelites pitch camp at the foot of Mount Sinai/Choreiv.

Then Amaleik came and would do battle with Israel at Refidim. And Moses said to Joshua: “Choose men for us and go out, wage battle against Amaleik! Tomorrow I will station myself on the top of the hill, and the staff of God will be in my hand.” (Exodus 17:8-9)

Nobody expects Moses to be a war leader. He is God’s prophet and deputy; when a warlike band of Amalekites appears, Moses appoints Joshua as the military general. Moses also decides to spend the day of the battle on top of a low hill where the Israelite troops can see him holding the staff. God does not need to instruct Moses this time; he has already taken charge.

Malbim, another 19th-century commentator, wrote “Moshe’s special abilities lay in the realm of the supernatural. … On this occasion, by contrast, God hid His face so that they were required to do battle in a natural manner. Therefore Moshe delegated command to Yehoshua, who had been chosen by God to lead the conquest of Canaan, which was to be accomplished through natural wars accompanied by hidden miracles.”9

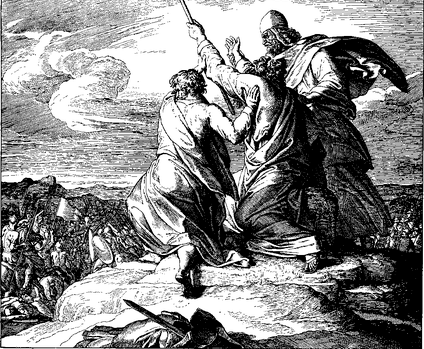

Moses climbs to the top of the nearby hill with his brother Aaron and another trusted assistant, Chur.

And it happened that when Moses raised his hand, Israel prevailed. And when he rested his hand, Amaleik prevailed. Then Moses’ hands were keveidim. So they took a stone and placed it under him, and he sat down on it, and Aaron and Chur supported his hands, one on this side and one on the other side. And his hands were steadfast until the sun came in [went down].” (Exodus 17:12)

keveidim (כְּבֵדִים) = heavy. (From the same root as ikavdah,אִכָּבְדָה,in Exodus 14:18 above = I will be considered impressive, I will be honored, I will be respected.)

According to the 13th-century commentary Chizkuni, Moses’ motivation was “to be able to follow the course of the battle while personally watching, and even more, so that the Israelite fighters could see their leader and be encouraged by this visual contact … Moses’ staff in this instance served as a flag for the Israelites fighting Amalek.”10

And Joshua disabled Amaleik and his people with the edge of the sword. (Exodus 17:13)

Enough Amalekites are killed or wounded so that they give up and run away. The immediate cause of the Israelites’ victory is that they keep swinging at the Amalekites with swords (which they must have taken from Egyptians, along with the gold, silver, and clothing). But they have the confidence to attack instead of retreat only when they see Moses holding up the staff of God.

Moses has had enough mentoring by God, and enough practice being the leader of thousands, that this time he acts on his own initiative and does exactly the right thing to save his people. He has become a worthy co-leader with God.

To be continued …

- Exodus 12:37 says: The Israelites journeyed from Ramses to Sukkot, about 600,000 fighting men on foot, apart from non-walkers. This would mean the total number of Israelites was more than a million, which would take more miracles than the book of Exodus reports to keep alive in the arid wilderness. The next verse, Exodus 12:38, says: And also riffraff went up with them …

- On Moses’ increasing self-confidence, see my post: Shemot to Bo: Moses Finds His Voice. On the courtiers, see Exodus 11:3: The man Moses was very great in the land of Egypt, in the eyes of Pharaoh’s courtiers and in the eyes of the people. The pharaoh reveals his growing respect for Moses in more subtle ways. The first time Moses and Aaron speak to him, he rejects their request out of hand (Exodus 5:1-9). After the second plague, the pharaoh summons Moses and Aaron and says if they will plead with God to remove the frogs, he will let the people go (Exodus 8:4). He keeps making these deals, then backing out on them, but at least he views Moses as someone who has God’s ear and must be negotiated with. When the pharaoh and Moses make another deal after the fourth plague, Moses adds: “Only may Pharaoh not deceive us again …” (Exodus 8:25)—and the pharaoh swallows the insult. During the final plague, death of the firstborn, the pharaoh begs Moses and Aaron not only to take the Israelites out of Egypt with no conditions, but also to bring a blessing upon him (Exodus 12:31-32).

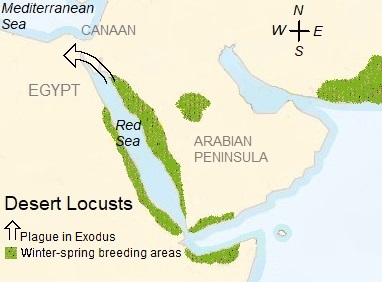

- The Hebrew word for this body of water is yam suf (יַם־סוּף), which means “Sea of Reeds”. It is commonly translated as the Red Sea, since the northern tip of the Red Sea is one possibility for the Israelites’ crossing point.

- Tur HaArokh, by Rabbi Jacob ben Asher, written circa 1280–1340 C.E., translation in www.sefaria.org.

- See Exodus 14:4.

- Robert Alter, The Five Books of Moses: A Translation with Commentary, W.W. Norton & Co., New York, 2004, p. 412.

- Exodus 3:1.

- Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch, The Hirsch Chumash: Sefer Shemos, translation by Daniel Haberman, Feldheim Publishers, Jerusalem, 2005, p. 293.

- Malbim (19th-century rabbi Meir Leibush Weisser), translation in www.sefaria.org; I substituted “God” for “Hashem” for clarity.

- Chizkuni, by Chizkiah ben Manoach, 13th century, translation in www.sefaria.org.