What are the worst curses you can imagine?

A slew of curses that will result if the people do not obey God appear in this week’s Torah portion, Ki Tavo (Deuteronomy 26:1-29:8). This section begins:

But it will be, if you do not heed the voice of God, your God, by observing and doing all [God’s] commands and decrees which I command you today, then all these curses will come upon you and overtake you. (Deuteronomy 28:15)

The first curses in this section of the Torah portion use general language, such as:

Cursed will you be in your comings, and cursed will you be in your goings. (Deuteronomy 28:19)

But then the Torah moves to curses about specific areas of life, including the curse of failure in whatever you try to accomplish.

God will send against you the malediction, the vexation, and the reproach, against every undertaking of your hand that you do, until you are annihilated and you perish quickly because of your evil deeds when you abandoned me. (Deuteronomy 28:20)

This sentence ends in the first person, with God reacting personally to being disobeyed, feeling abandoned.

But it opens in the third person, stating that God will reproach the disobedient Israelites by thwarting every effort they make to thrive. 19th-century rabbi Hirsch explained: “Consequent to the sin, inner serenity disappears and is replaced by inner disquiet, and by a constant feeling of reproach, self-reproach, the consciousness that one deserves God’s censure. … Inner disquiet and a constant mood of self-reproach will prevent the success of your labors.”1

This is an apt psychological explanation for why some people cannot bring their undertakings to completion. But what about the threat of being annihilated and perishing quickly? Many people live with guilt and self-reproach for decades, depressed but not annihilated.

Next the Torah describes how the disobedient Israelites will be cursed by diseases, drought, and defeat in battle—all potentially deadly. Then we return to the failure of people’s enterprises.

And God will strike you with shiga-on and with blindness and with confusion of mind. And you will grope around at midday the way the blind grope around in their [own] darkness, and your ways will not prosper; and indeed you will be exploited and robbed all the time, and there will be no rescuer. (Deuteronomy 28:28-29)

shiga-on (שִׁהָּעוֹן) = madness, insanity. (From the root verb shaga, שָׁגַע = acted insane.)

Since blindness is listed between insanity and confusion, it probably means the inability to foresee or understand anything, rather than a literal lack of vision.

Hirsch explained: “You will not have a clear perception of things and of the circumstances; hence, nothing that you do will achieve the desired end. Others, first and foremost the neighboring nations, will take advantage of your perplexity so as to rob you of your rights.”2

Three milestones

The portion Ki Tavo then lists three deeds that require a major investment of a man’s time and money in order to reap a deeply satisfying reward. For all three, the disobedient Israelites will never get the reward.

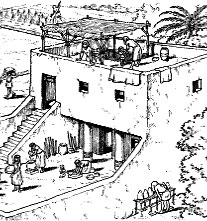

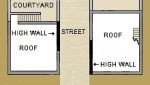

A woman you will betroth, and another man will use her for sex. A house you will build, and you will not live in it. A vineyard you will plant, and you will not use it. (Deuteronomy 28:30)

Arranging a marriage in the Torah included negotiations with the woman’s family and the payment of a bride-price; the reward was not only a sex partner, but a companion, a worker, and a mother of one’s children. Building a house was also a big enterprise with a long-term reward. And grape vines, like fruit trees, had to be cultivated for three years without a harvest; only in the fourth year could they be picked for food, wine, and profitable trade.

The Torah portion Shoftim, earlier in Deuteronomy, treats the same three things as milestones in a man’s life. Officials who are recruiting troops are supposed to say:

“Who is the man that has built a new house and has not dedicated it? Let him go and return to his house, lest he die in the battle, and another man dedicate it. And who is the man that has planted a vineyard and has not used it? Let him go and return to his house, lest he die in the battle, and another man harvest it. And who is the man that has betrothed a woman and has not taken her [in marriage]? Let him go and return to his house, lest he die in the battle, and another man take her.” (Deuteronomy 20:5-7)3

No man wants to die before marrying, moving into his own house, and harvesting from his own grapevines (or fruit trees). If the Israelites are behaving well, following God’s directions, men can be excused from military service in order to enjoy reaching these milestones. Other men can go off to invade towns outside Israel’s borders, and God will give them success in battle.4

But if Israelites are behaving badly, flouting God’s directions, then they will be invaded by outsiders who seize their fiancées, their houses, and their vineyards.

Last week’s Torah portion, Ki Teitzei, expands on one of these military exemptions:

When a man takes a new wife, he must not go out with the troops, and he must not cross over to them for any matter. He will be exempt for his household one year and give joy to his wife whom he has taken. (Deuteronomy 24:5)

We can imagine the recruits crossing the town square to stand on one side, while the men who are staying home remain on the other side. This verse also informs us that the exemption from military service lasts for a year, and that a man must “give joy” to his new wife.

A wife in ancient Israel was not just a baby-making, bread-kneading, thread-spinning machine. She was supposed to be able to enjoy sex with her husband, and to be content with her new life in his household.

The Talmud adds that the exemptions for a new house and a newly mature vineyard also last for a full year.

“Since the wife needs twelve months, also all of them need twelve months.” (Talmud Yerushalmi, Sotah 8:8:2)5

“Those who are exempt for these reasons do not even provide water and food to the soldiers, and they do not repair the roads.” (Talmud Bavli, Sotah 43a)5

Thwarted by enemies

But when the Israelites disobey God, no one will get a year off for settling into a new marriage, a new house, or a new addition to their livelihood. Instead, God will let outsiders invade Israel and win. This week’s Torah portion continues:

Your ox will be slaughtered in front of your eyes, and you will not eat from it. Your donkey will be stolen in front of you, and it will not return to you. Your flock will be given to your enemies, and there will be no rescuer for you. Your sons and your daughters will be given to another people, and your eyes will be seeing and longing over them every day, but there will be no strength in your hand. The fruit of your land, and everything you toiled for, will be consumed by a people you do not know, and you will only be exploited and crushed all the time. (Deuteronomy 28:31-33)

The laws laid down by God through Moses mandate returning stray animals to their owners,6 provide redemption for children sold as slaves, and even make the sale of land temporary.7 But invaders from other countries would disregard the local laws, and act only for their own benefit. Ironically, God will let the invaders succeed because the Israelites have been disregarding laws and acting only for their own benefit!

The curses that result from invasion by enemies are communal punishments, occurring when the people as a whole disobey God’s laws. Ethical and law-abiding individuals or families do not get special treatment when enemies invade.

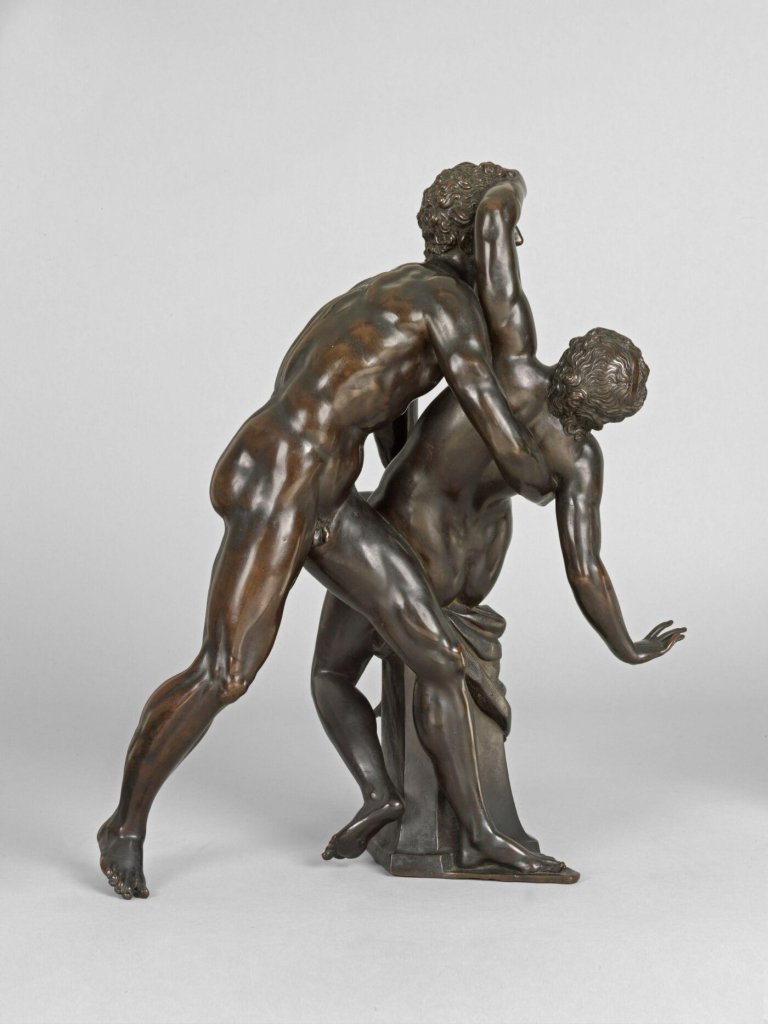

Insanity

And you will be meshuga from the sight that you see with your eyes. (Deuteronomy 28:34)

meshuga (מְשֻׁגָּ֑ע) = insane, crazy, raving. (Also from the root verb shaga, שָׁגַע, otherwise used only in the hitpael form: hishtaga-a, הִשְׁתַּגַּעַ = behaved like an insane person, or mishtaga-a, מִשְׁתַּגַּעַ = was behaving like an insane person.)

Ha-Emek Davar, a collection of 12th and 13th-century commentary, explained: “You will be amazed that you have become like this. That a few bandits have done so much damage, and your strength cannot save you, even though really it should have been strong enough against them. From this you will become insane and go out of your minds.”8

If the conquerors were merely a group of bandits, the Israelites might be driven mad by an inability to understand why they had not been able to defeat them. Only a few Israelites would attribute their unlikely failure to defend their land to a divine curse. If the conquerors were a large army, more Israelites might realize that God was no longer on their side, and remember that they needed God’s help. Either way, the Israelites could only explain their defeat if they acknowledged that they had done wrong and disobeyed their God.

It is human nature to cling to the belief that you are right and righteous, and to resist admitting that your actions have been unethical.

In a world-view with a God who administers rewards and punishments for collective behavior, the only responses to the total frustration of our plans and dreams are to admit our own bad behavior, to blame only the people around us, or to plunge into the mental blindness of believing that everything you are suffering is all for the best.

Without a God-centered world-view, there is a fourth option: to believe that tragedies sometimes happen when no one is at fault. This belief is easy to maintain when inexplicable tragedies are happening to people you don’t know. But it could lead to a mental breakdown when tragedies happen to you.

No wonder we feel cursed when undertakings we have nurtured for years are suddenly annihilated. Admitting collective guilt, blaming others, believing it’s all for the best, shrugging it off as bad luck, and going a little crazy are all possible responses. If, God forbid, it happened to you, what would your response be?

- Samson Raphael Hirsch, The Hirsch Chumash: Sefer Devarim, translated from German by Daniel Haberman, Feldheim Publishers, Jerusalem, 2009, p. 667.

- Ibid., p. 670.

- See my post Shoftim: More Important than War, Part 1.

- Deuteronomy 20:1.

- Translations of both Talmud Yerushalmi and Talmud Bavli are from www.sefaria.org.

- Deuteronomy 22:1-3.

- Deuteronomy 25:25-46.

- Ha-Emek Davar, commentary by the 12th to 13th-century Tosafists, translated in www.sefaria.org.