(If you want to read one of my earlier posts on this week’s Torah portion, Ki Teitzei (Deuteronomy 21:10-25:19) you might try: Ki Teitzei: Virtues of a Parapet. Below is the fifth post in my series on why David is God’s favorite king—whether he acts ethically or not.)

The first king of the Israelites is Saul, who was anointed by the prophet Samuel at God’s command. But Saul turns out to be an unsatisfactory king, from Samuel and God’s point of view; he is more concerned about keeping his troops happy than about following God’s rules.1 So God tells Samuel to secretly anoint David as the next king.

And Samuel took a horn of oil and anointed him in the midst of his brothers. And the ruach of God rushed through David from that day and onward. Then Samuel got up and went [back] to Ramah. Then the ruach of God turned away from Saul, and a malignant ruach from God terrified him. (1 Samuel 16:13-14)

ruach (רוּחַ) = wind; spirit, disposition.

The malignant ruach afflicts King Saul with bouts of paranoia, in which he is terrified that David, his loyal army commander, will kill him and seize his throne. While he is in the grip of this spirit, he throws a spear or javelin at David twice. Later, when Saul’s own son and heir, Jonathan, questions his plan to kill David, Saul throws a spear at him, too. The king even orders a whole town of Israelite priests and their families massacred because the high priest helped David to escape.2

David becomes the leader of an outlaw band moving from place to place as King Saul tries to hunt them down. Yet there is no revolution, and no coup. David does not become the king until many years later, after Saul has died in a battle with the Philistines. Why does David wait?

The king’s robe

On one expedition Saul takes 3,000 men to En-Gedi, where he has heard that David and his 600 outlaws are hiding. Saul steps into a cave to defecate in private. He has no idea that the cave is large enough to hide hundreds of men, who are sitting in the recesses of the cave behind him.

Then David’s men said to him: “Here is the day about which God said to you: ‘Hey, I myself give your enemy into your hand!’ And you can do whatever seems good in your eyes to him!” And David got up and stealthily cut off the corner of Saul’s me-il. (1 Samuel 24:5)

me-il (מְעִיל) = a robe worn over the tunic by members of the royal family, high priests, and Samuel (who was a priest before becoming a prophet and judge).

Nowhere in the first book of Samuel does God promise to give an enemy into David’s hand. But David’s men are hoping to motivate him to kill Saul, without saying so directly.

They fail. Instead of stabbing Saul from behind, David merely collects evidence that he could have done so if he had chosen.

And he said to his men: “Far be it from me, by God, if I should do this thing to my lord, to God’s anointed, to stretch out my hand against him! For he is God’s anointed!” (1 Samuel 24:7)

This is an interesting statement by someone who is also God’s anointed. Perhaps David is so awed by his own anointment that he is also awed by Saul’s status. Or perhaps he is planning ahead, setting an example so that when he himself is the king, his subjects will treat his life as sacred, too.

When Saul stands up and walks out, David restrains his men. Then he steps out of the cave and calls after the king. Saul turns around, and David prostrates himself at a distance. He immediately starts talking, probably so that Saul will listen to him instead of calling his soldiers. Partway through his oration, David points out that he could have killed Saul while the king was squatting in the cave.

“But I had compassion on you, and I said: ‘I will not stretch out my hand against my lord, for he is God’s anointed.’ And see too, my father: see the corner of your me-il in my hand! For when I cut off the corner of your me-il I did not kill you! Know and see that there is no evil or rebellion in my hand, and I did not do wrong against you. Yet you are lying in wait to take my life!” (1 Samuel 24:9-12)

By saying he had compassion on Saul, David puts the idea of compassion into Saul’s mind. By prostrating himself to Saul and calling him “my father” (which acknowledges Saul’s position as both his king and his father-in-law3), he subtly invites the king to be solicitous toward his inferior.

Although David promises that he will never make a move against Saul, he implies that God will:

“Let God judge between me and you, and let God take vengeance for me upon you, but my hand will not be against you!” (1 Samuel 24:13)

If David is hinting to God, God does not respond. David elaborates on his theme until Saul finally answers.

“Is this your voice, my son David?” And Saul lifted up his voice and wept. And he said to David: “You are more righteous than I am, because you have repaid me with goodness, and I have repaid you with evil.” (1 Samuel 24:17-18)

David has succeeded in touching Saul’s good (and rational) ruach. His gamble pays off. Instead of ordering his troops to attack the cave, Saul goes home. The king does not go as far as inviting David to resume his old position in court, and David knows better than to ask.

Before long, Saul’s paranoid ruach overcomes his good ruach again, and he sets off with another troop of soldiers to hunt down David in the wilderness.

Since he knows how changeable Saul is, why does David cut off the corner of the royal robe, then step out to speak to Saul? He could have just stayed in hiding.

My guess is that David puts on a show to satisfy his men. Since he is unwilling to kill Saul, he stages a piece of theater for them that makes him look bold and noble.

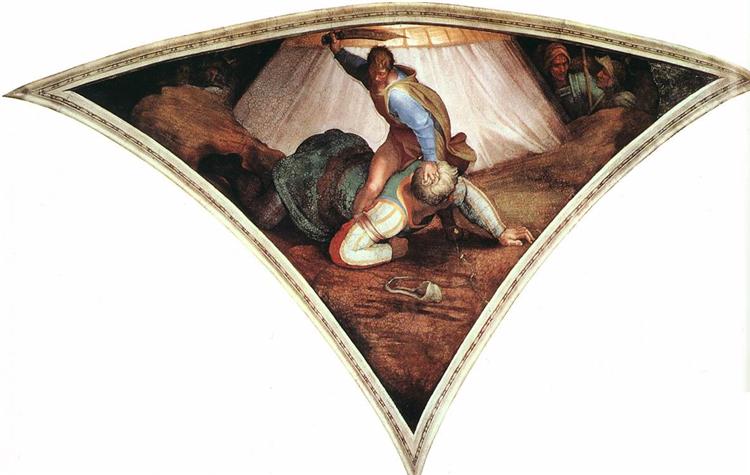

The king’s spear

When David and his outlaws are in the wilderness of Zif, some locals report it to King Saul, who collects 3,000 men and sets out again. At night David looks down at the king’s campsite from a hilltop. Saul and his general, Abner, are asleep in the middle of the camp, surrounded by their sleeping troops. Near Saul’s head is a water jug, and the king’s spear, thrust into the ground. David’s nephew Avishai says:

“Today God has delivered up your enemy into your hand! And now, please let me strike him into the ground with the spear, one time! I will not [need to do it] twice to him!” (1 Samuel 26:8)

Avishai is bragging that he can kill Saul with one blow, so nobody in the camp will hear a cry. He is confident that he is a better spear thrower than the king, who missed David twice and Jonathan once.

But David said to Avishai: “You must not destroy him! Because who stretches out his hand against God’s anointed and is exempt from punishment?” (1 Samuel 26:9)

David’s disappointed nephew is silent. David says:

“… God will smite him instead. Either his day will come and he will die, or he will go down in battle and be snatched away. Far be it from me, by God, to stretch out my hand against God’s anointed! And now, please take the spear that is at his head, and the jug of water, and we will go on our way.” (1 Samuel 26:10)

Once again, David emphasizes the importance of doing no harm to God’s anointed king. Taking a symbol of kingship is different, however, whether it is the king’s spear or a corner of his robe.

Then David steals down and takes the spear and water jug himself, perhaps concerned that his young nephew might kill Saul despite his orders. This is when God enters the picture and demonstrates approval of David’s restraint.

And there was no one who saw, and no one who knew, and no one who was rousing, because all of them were sleeping—because the deep slumber of God had fallen upon them. (1 Samuel 26:12)

When David is safely back on the hilltop, he shouts and wakes up everyone below. He accuses General Abner and his men of failing at their job.

“… You did not keep watch over your lord, over God’s anointed! And now, see: Where are the king’s spear, and the jug of water that was at his head?” (1 Samuel 26:16)

Once again, David refers to “God’s anointed”. This way of describing a king reflects his own attitude toward kingship, but it is also a good seed to plant in the minds of the soldiers for the day when David reveals he, too, is God’s anointed.

And Saul recognized David’s voice, and said: “Is this your voice, my son David?” And David said: “My voice, my lord king.” (1 Samuel 26:17)

This time Saul begs David to come back, and promises that he will never do anything bad to David again. But David merely orders someone to return the king’s spear. His last words to Saul are:

“Today God gave you into my hand, but I was not willing to stretch out my hand against God’s anointed. And hey! As your life has been important today in my eyes, so may my life be important in God’s eyes, and may [God] rescue me from every distress!” (1 Samuel 26:23-24)

Here David is really addressing God. Robert Alter wrote that David “hopes that God will note his own proper conduct and therefore protect him.”5

The king’s death

Tired of being hunted by King Saul, David takes his whole band of outlaws across the border into Philistine territory. While David and his men are in the Philistine village of Ziklag, there is a major battle between the Philistines and the Israelites in the Jezreel Valley in Israelite territory. The Philistines win and occupy the Jezreel, the Israelites who are not killed flee, and Saul and three of his sons, including Jonathan, die on the battlefield. Saul, wounded by arrows, asks his weapons-bearer to finish him off, but the man is feel so awed and fearful that he refuses. David is not the only Israelite who believes a king anointed by God is sacrosanct! So Saul dies by falling on his own sword.6

The second book of Samuel opens with a young man running from the battlefield all the way to Ziklag. He prostrates himself to David, then tells him what happened. His story of how King Saul died is different:

“… he turned around and he saw me and he called out to me, and I said: ‘Here I am’. And he said to me: ‘Who are you?’ And I said to him: ‘I am an Amalekite”. And he said to me: ‘Stand over me, please, and give me the death-blow, because weakness has seized me, though life is still in me.’ Then I stood over him and I gave him the death-blow, since I knew that he could not live long after having fallen. Then I took the circlet that was on his head and the bracelet that was on his arm, and I brought them to my lord here.” (2 Samuel 1:7-10)

According to Robert Alter: “A more likely scenario is that the Amalekite came onto the battlefield immediately after the fighting as a scavenger, found Saul’s corpse before the Philistines did, and removed the regalia. … he sees a great opportunity for himself: he will bring Saul’s regalia to David, claim personally to have finished off the man known to be David’s archenemy and rival, and thereby overcome his marginality as a resident alien … by receiving a benefaction from the new king …”7

But the Amalekite does not know that an anointed king is sacrosanct in David’s eyes. David rips a tear in his clothes in mourning, and demands:

“How were you not afraid to stretch out your hand to destroy God’s anointed!” (2 Samuel 1:14)

Then he has the Amalekite executed.

David could have interpreted his anointment by a prophet in the name of God as permission to supersede the previously anointed king as soon as possible. Instead, he takes the position that anyone who is “God’s anointed” is sacrosanct, and any attempt to kill that person is a crime against God.

During the period when David is an outlaw, he bends a few rules. But he also consults God through oracular devices and does what God says;8 and he maintains that the life of anyone whom God has had anointed is sacred. His attitude toward God keeps him in God’s favor. So God helps him by casting a deep sleep over Saul’s camp while David steals the king’s spear.

Can this warm relationship between David and the God character continue even when David goes to work for the Philistine king who is the chief the enemy of Israel? We shall see in next week’s post, 1 Samuel: David and the King of Gat.

- 1 Samuel 10:19-22, 15:9-11. See my first post in this series: 1 Samuel: Anointment.

- Saul throws spears at David in 1 Samuel 18:9-12, 19:9-11, and at Jonathan in 1 Samuel 20:30-33. (See my third post in this series: 1 Samuel: David the Beloved.) Saul has everyone in the town of Nov massacred in 1 Samuel 22:16-19. (See my fourth post in this series: 1 Samuel: David the Devious.)

- David is married to Saul’s second daughter, Mikhal. She helped him to escape their house when Saul’s men came to kill him, but David never tried to arrange for her to leave and join the outlaws. See my post: 1 Samuel: David the Beloved.

- 1 Samuel 24:20-21.

- Robert Alter, Ancient Israel: The Former Prophets, W.W. Norton &Co., New York, 2013, p. 399.

- 1 Samuel 31:1-7.

- Alter, pp. 426-427.

- See my post: 1 Samuel: David the Devious.