Before giving Moshe (“Moses” in English) the first pair of stone tablets at the summit of Mount Sinai, God gives him instructions for founding a new religion, featuring priests and a portable tent-sanctuary. The instructions begin with this week’s Torah portion, Terumah (Exodus/Shemot 25:1-2:19), which opens:

And God spoke to Moshe, saying: “Speak to the Israelites, and they must take for me a terumah; from every man whose heart urges him on, you will take my terumah.” (Exodus 25:1-2)

terumah (תְּרוּמָה) = voluntary contribution lifted up and offered to God. (From the root verb rum, רוּם = to be high, to be exalted.)

In other words, God is inviting people to make gifts because they want to. A list of materials to contribute follows, but no contributions are mandated. Furthermore, according to Chayim ibn Attar: “… a person should not make a contribution until he was in the proper frame of mind. … The Torah also may wish to teach that the term ‘my gift,’ cannot be used except when the donor has donated it willingly, generously, with all his heart.”1

Proposed gifts

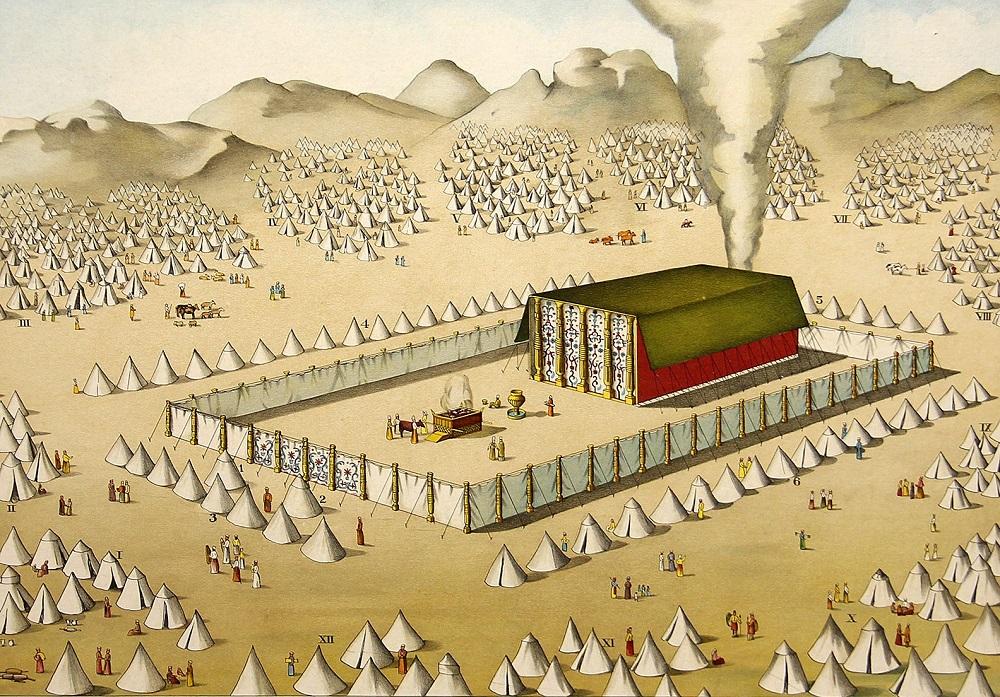

All the materials that God requests (or proposes) will be used to fashion a portable sanctuary and its implements, and to make vestments for the priests of the new religion. Gold, silver, and four kinds of yarn (blue, red-violet, and scarlet wool, and bleached linen) are needed for both the sanctuary and the vestments. Acacia wood is needed for the framework of the sanctuary and its courtyard, and for the walls of the sanctuary (which will be covered with fabric inside and out). Goat’s hair yarn and two kinds of leather are needed for the three roof coverings to be draped over a wood framework. Copper (or brass or bronze) is needed for the altar and the wash-basin outside the sanctuary, and for clasps and sockets in the areas that do not require silver. Precious stones will be sewn onto the high priest’s vestments, incense spices are needed for one of the high priest’s duties, and olive oil is needed for inaugurating priests.

Why do the Israelites have all these materials? Harold Kushner pointed out: “The gold, silver, and jewels that the Israelites would give were taken from the Egyptians when they left Egypt. They were not to be used for personal benefit but for something holy and transcendant.”2

The Israelites also “borrowed” clothing from their Egyptian neighbors, which might have contained the woolen yarn colored with expensive dyes, and the linen threads. The Israelite women already had copper mirrors, and presumably copper pans, spices, and olive oil that they packed them for the journey.

Yet no matter where the materials came from, they are all made from things that God (as the creator of nature) originally provided. Considering this, many Israelites might feel moved to give something back to God. And the act of giving is in itself beneficial. Jonathan Sacks wrote: “To be in a situation where you can only receive, not give, is to lack human dignity.”3

A small space

After listing the materials to be donated, God tells Moshe:

“Then let them make me a holy-place, and veshakhanti among them. Like all that I myself show you, the pattern of the mishkan and the pattern of all its furnishings, thus you should make it.” (Exodus 25:8-9)

veshakhanti (וְשָׁכַנְתִּי) = and I will dwell, and I will settle. (From the verb shakhan, שָׁכַן = dwell, settle, stay, inhabit.)

mishkan (מִשְׁכָּן) = dwelling place, home. (From the root verb shakhan. Out of 137 occurrences of the word mishkan in the Hebrew Bible, only 12 refer to human rather than divine dwelling places.4 The mishkan of God is often called a “tabernacle” in English.)

If they build it, God will come. But how could God live in a structure that will be, according to God’s subsequent instructions, only 10 x 20 cubits (about 15 x 30 feet or 4½ x 9 meters)?

Many classic commentators pointed out that God is too vast to fit inside. They cited biblical passages such as: “Behold, the heavens and the heaven of heavens cannot contain You” (I Kings 8:27); “Do I not fill heaven and earth?” (Jeremiah 23:24); and “The heavens are My throne, and the earth is My footstool” (Isaiah 66:1).

In the 14th century Bachya ben Asher explained that only God’s kavod (כָּבוֹד = glory, magnificence, impressiveness) would dwell inside the mishkan. God’s kavod previously appeared as a pillar of cloud and fire, then as the cloud and fire on Mount Sinai. Now it would manifest above the ark in the back chamber of the sanctuary, called the Holy of Holies.

Other commentators have noted that God says: “make me a holy-place, and I will dwell among them”—not “inside it”.

For example, in the 19th century Malbim wrote: “He commanded that each individual should build him a sanctuary in the recesses of his heart, that he should prepare himself to be a dwelling place for the Lord … as well as an altar on which to offer up every portion of his soul to the Lord …”5

This has become a popular interpretation in modern times. But it begs the question of why God asks the Israelites to build a structure made out of wood, metal, fabric, and leather.

Insecurity

When God dictated a long list of laws to Moshe right after the revelation to all the Israelites at Mount Sinai, one of the first things God said was:

An altar of earth you may make for me, and you should slaughter upon it your complete-burned offerings and your wholeness offerings, your sheep and your cattle. In every place where I cause my name to be remembered, I will come to you and I will bless you. (Exodus 20:21)

Since God is everywhere, and can come to people anywhere, why do the Israelites now need to build an elaborate temporary structure for God to dwell in?

One proposed reason why God calls for a mishkan is that it will help to convince the Israelites that God is with them. Just before Moshe comes back down the mountain with the instructions for making the mishkan, the Israelites in the camp are ordering Aharon (“Aaron” in English) to make them “a god that will go before us” (Exodus 32:1). As I wrote in my post Beha-alotkha & Ki Tisa: Calf Replacement, once the people believe they will never see Moshe again, they cannot bear to go on without at least an idol. So Aharon makes the golden calf.

Does God know ahead of time that the Israelites will want a concrete symbol of the divine? Or, as much classic commentary claims, are the passages in the book of Exodus out of order regarding the timing of events? Either way, the people are insecure, prone to feeling abandoned, and God orders the building of the mishkan.

Cassuto wrote: “… the children of Israel, after they had been privileged to witness the Revelation of God on Mount Sinai, were about to journey from there and thus draw away from the site of the theophany. … it seemed to them as though the link had been broken, unless there were in their midst a tangible symbol of God’s presence among them.”6

We learn in the book of Numbers that when the Israelites do finally march north from Mount Sinai, God’s manifestation as cloud by day and fire by night returns to guide them and signal when they should break camp.7 But the people do not know ahead of time that this will happen. And they need something concrete to reassure them right away.

Making something

Commentators through the centuries have proposed additional reasons why God wants the Israelites to build a mishkan. One of my favorites appears in Bamidbar Rabbah:

“You find that all the days that they were engaged in the labor of the Tabernacle, they were not complaining. When they completed the labor of the Tabernacle, the Holy One blessed be He was shouting: Woe, let them not return to complaining like they used to complain.”8

Personally, I find that there is nothing like doing creative, self-directed work to take my mind off my worries. And the Israelites get something close to that.

In the Torah portion Ki Tisa, before God gives Moshe the first pair of stone tablets, God appoints a master craftsman and his assistant (Betzaleil and Ohaliav) from among the Israelites, and hints that other skilled people will work under their supervision.9 When Moshe passes on God’s instructions to the people in the portion Vayakheil, he says outright:

And everyone wise of mind among you should come and make everything that God has commanded. (Exodus 35:10)

Then both men and women donate materials, and both men and women use their skills to make the pieces of the mishkan and the priests’ vestments. And during that whole year, nobody rebels, grumbles, or complains.

Changing

Could the experience of working together to create all these things for God permanently change the Israelites’ attitude? Jonathan Sacks thought so when he wrote: “The Tabernacle did not last forever, but the lesson it taught did. It is not what God does for us that transforms us, but what we do for God. … It is what we do, not what is done to us, that makes us free. That is a lesson as true today as it was then.”10

Sacks explained: “When a central power—even when this is God Himself—does everything on behalf of the people, they remain in a state of arrested development. They complain instead of acting. They give way easily to despair. When the leader, in this case Moses, is missing, they do foolish things, none more so than making a Golden Calf. There is only one solution: to make the people co-architects of their own destiny, to get them to build something together, to shape them into a team and show them that they are not helpless, that they are responsible and capable of collaborative action.”11

Yet making the mishkan and the priests’ vestments does not lead to a permanent change in the Israelites’ self-confidence or attitude toward God. Perhaps the problem is that they do all the craftsmanship in their camp at the foot of Mount Sinai, where they have water, daily manna, grazing for their livestock, and no enemies. Once the Israelites leave Mount Sinai, the complaints and rebellions start up again—mostly because the men (former slaves who have fought in only one clash)12 have no confidence in their ability to conquer Canaan by force of arms. Nobody is training them for war, and they cannot believe that God will provide enough magical help to make them win. Only after the Israelites have spent 40 years in the wilderness does the next generation march in and begin the conquest.

What if you had never had a chance to take initiative, to make decisions about your life, or to use your own talents—and then suddenly, like the Israelites, you were invited to contribute to a major creative project?

I lived under my mother’s thumb until I was 17 and I escaped to college. Like the Israelites eating manna and camping below Mount Sinai, I was not completely independent; my parents still paid for my expenses. But I lived in a dorm, I chose my own friends and my own classes, I did my own work, and I earned appreciation and respect. When my mother tried to take over my life again, I rebelled. I made mistakes, but I managed to become an adult.

The Israelites in the book of Exodus have one glorious year as volunteers making the mishkan. But once they finish, they have to go back to being dependent and following orders. No more contributions of their own are accepted. And they do not view God or Moshe as benign parents in the book of Numbers, because they are marching toward what they assume is pointless death at the hands of the Canaanites. Naturally they lapse back into complaining. Yet somehow, they raise their own children to be more confident in God and more confident in themselves. That is the way they achieve a permanent change.

- Rabbi Chayim ibn Attar, Or HaChayim, 18th century, translated in www.sefaria.org.

- Rabbi Harold Kushner, editor of d’rash commentary, Etz Hayim, The Rabbinical Assembly of The United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism, 2001, p. 486. See Exodus 3:21-22, 11:2-3, and 12:35-36.

- Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks, Essays on Ethics, A Weekly Reading of the Jewish Bible: “The Labor of Gratitude: Terumah”, reprinted in www.sefaria.org.

- Numbers 24:5; Isaiah 22:16, 54:2; Jeremiah 19:18; Ezekiel 25:4; Habakuk 1:6; Psalms 49:12, 87:2; Job 18:21, 21:28, and 39:6; and Songs 1:8.

- Malbim (acronym of 19th-century rabbi Meir Leibush Weisser), quoted by Nehama Leibowitz, Studies in Shemot, translated by Aryeh Newman, The Joint Authority for Jewish and Zionist Education, Jerusalem, 1996, p. 483.

- 20th century rabbi Umberto Cassuto (a.k.a. Moshe David Cassuto) quoted by Leibowitz, ibid., p. 484.

- Numbers 9:15-23.

- Bamidbar Rabbah, 11th or 12th century, translation in Rabbi Chayim ibn Attar, Or HaChayim, 18th century, translation in www.sefaria.org.

- Exodus 31:1-13.

- Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks, 21st century, Covenant & Conversation, “Building Builders: Terumah”.

- Sacks, Covenant & Conversation, “The Home We Build Together: Terumah 5781” (2021).

- With the men of Amaleik in Exodus 17:8-13.