Simchat Torah (“Joy of the Torah”) is the day when, besides dancing with the Torah scroll, Jews read the end of Deuteronomy/Devarim, then roll the Torah scroll all the way back to the beginning and start reading Genesis/Bereishit. The annual cycle of Torah portions begins again!1

Then for Shabbat this Saturday morning we read from the first Torah portion in Genesis. In this blog post, let’s look at the darkness at the beginning of the book.

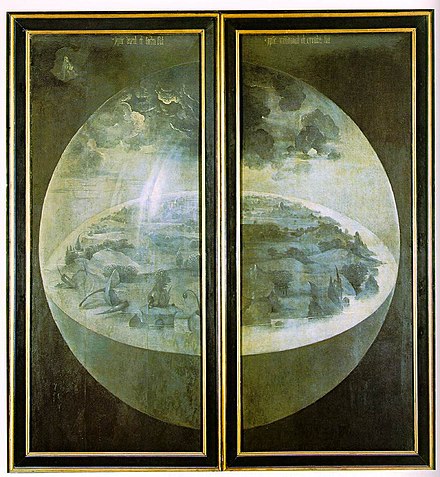

Darkness before light

The book of Genesis begins with a grand poetic work describing six days of creation and a seventh day of rest. It opens by stating the subject of the composition:

At the beginning God created the heavens and ha-aretz. (Genesis/Bereishit 1:1)

ha-aretz (הָאָרֶץ) = the earth, the land, the ground; the world.

In Genesis 1:1 it means “the earth”, since the heavens and the earth together make the created world. In the next verse, we learn that God does not create the world ex nihilo, out of nothing. What already existed before God begins to speak was dark, shapeless, and watery.

And ha-aretz had been2 undifferentiated unreality, and darkness over the face of tehom; and the breath of God hovered over the surface of the water. (Genesis 1:2)

In this verse, the best translation for ha-aretz is “world”, since it refers to what existed before there was a solid mass of earth (or, in today’s terms, a planet). “Undifferentiated unreality” is one translation for tohu vavohu (תֺטוּ וָבֺהטוּ). The “breath” of God is one translation for God’s ruach (רוּחַ). (See my post Bereishit: Before the Beginning for alternate translations of tohu vavohu and ruach.)

The Hebrew word for darkness is choshekh (חֺשֶׁךְ), which captures both the literal usage and many of the same metaphorical usages as in English. But the darkness is over the surface of something else: tehom.

tehom (תְהוֹם) = a source of deep water, i.e. an underground spring; the subterranean water beneath the earth.

In the second verse of Genesis, tehom probably means infinitely deep water, since the breathof God hovers “over the surface of the water”.

(As in much literature from the Ancient Near East, the Hebrew Bible pictures the universe as having four layers. The bottom is tehom, the water below, which extends downward infinitely, but is capped at the top by a layer of solid earth (with some rivers, lakes, and so forth). Above the earth is air and sky, the lower part of the heavens. The upper part of the heavens consists of more water: the water above, which extends upward infinitely.)

Both darkness and God’s “breath” are described as being over, or above, the tehom. So even though everything is undifferentiated unreality before God begins to create, there is in fact one distinction before creation: above and below. Either God is one of the things in the undifferentiated unreality above the tehom, or God is another category altogether, and only God’s hovering breath is there above the tehom.

Having established the situation before God begins to create, the text continues:

And God said: “Light, be!” And light was. And God saw the light, that it was good. And God separated the light from the darkness. And God called the light day, and the darkness night. And it was evening and it was morning, one day. (Genesis 1:3-5)

The separation of light from darkness creates the first day, consisting of a period of light (newly created) and a period of darkness (already there before God spoke).

So what does “darkness”, choshekh, mean in the first five verses of Genesis?

Is darkness visible?

Does “darkness” mean the absence of light, or is it something that is present, the way light is present? The clause “… and darkness was over the face of tehom …” implies that there was something above the surface of the water. If darkness meant the mere absence of light, the Torah could have said “… and nothing was over the face of tehom …”.

Furthermore, the curious sentence “And God separated the light from the darkness” implies that when light popped into being, it was mixed together with darkness at first. Then God began creating the orderly world by separating these two opposites, in time if not in space. The next verse says: “God called the light day, and the darkness night”.3

When God creates the plague of darkness in the book of Exodus, darkness seems like a visible and tangible substance.

And God said to Moses: “Stretch out your hand up to the heavens, and darkness will be over the land of Egypt, and [the Egyptians] will feel darkness!” And Moses stretched his hand up to the heavens, and gloomy darkness was in all the land of Egypt three days. A man could not see his brother, a man could not get up from his spot, for three days. But for all the Israelites, light was in their dwelling-places. (Exodus/Shemot 10:21-23)

The poetic image is of a darkness so dense that it presses against the skin. But then it becomes clear that the Egyptians are totally blind for three days, while the Israelites can still see light.

One tradition in Jewish commentary is that darkness did exist before God spoke light into being, but the darkness was invisible. (This begs the question of whether something can be invisible if there is nobody to see it.) The writer known as Pseudo-Philo, who lived circa 70-150 C.E., imagined King David singing: “Darkness and silence were before the world was made, and silence spoke and the darkness became visible.”4

This implies that God was the primordial silence, and darkness was the primordial light. First God changed, by speaking. Then God’s first words, “Light, be!” changed darkness into light, making it visible.

In the 12th or 13th century, Radak wrote that the darkness before God spoke was actually a type of fire, but it was invisible because it could not produce light. He added that this invisible fire is still present at night. “If this primordial fire would give off light, we would be able to see at nighttime. The night would appear to us as if it were aflame.”5

Is darkness bad?

And God saw the light, that it was good … (Genesis 1:4)

Does that mean merely that God identifies light as good? Or does it mean that darkness is bad by contrast?

The implication that light is good and darkness is bad appears as early as Second Isaiah, written in the 6th century B.C.E.:

Forming light and creating darkness, making peace and creating evil—I, God, am doing all these. (Isaiah 45:7)

But many commentators have objected to the idea that God creates, or created, evil. They take the view that there is only one God and God is good, so therefore evil must come from a different source. But what is the source? One common answer to the “Problem of Evil” is that God gave human beings free will, and therefore we sometimes choose to commit evil acts. But this does not explain another category of evil: the natural causes of diseases and disasters that make innocent people suffer.

One solution to the problem is that our world is “the best of all possible worlds”, the explanation of Gottfried Leibniz in his 1710 book known as the Theodicy. But the first chapter of Genesis indicates a different solution. Israel Knohl wrote:

“In my view, the Priestly description of Creation is an effort to solve this fundamental dilemma. The primeval elements tohu [undifferentiation], choshekh [darkness], and tehom [water below] all belong to the evil sphere. The three elements comprising the preexistent cosmic substance are the roots (put another way, the substance) of the evil in the world. At the conclusion of the Priestly account of Creation, it is written: ‘And God saw all that He had made, and found it very good’ (Gen. 1:31). All that God had made was very good. Evil was not made by God. It predated the Creation in Genesis 1!”6

But S.R. Hirsch pointed out that if we assume that God did not create darkness, we end up limiting God’s abilities:

“If matter had antedated Creation, then the Creator of the universe would have been able to fashion from the material given Him not a world that was absolutely good, but only the best world possible within the limitations of the material. In that case, all evil—natural and moral—would be due to the inherent faultiness of the material, and not even God would be able to save the world from evil, natural or moral.”8

Since Hirsch could not accept the idea that God is not omnipotent, he insisted that God created everything that ever was, including the darkness that existed before God created light. Then he maintained that God is omnibenevolent, and this is not merely the best of all possible worlds, but the only ultimately good world.

“This world—with all its seeming flaws—corresponds with the wise plan of the creator; He could have created a different world, has such a world corresponded with His Will. … Both, the world and man, will reach the highest ideal of the good, for which both were created. They will achieve this level of good because God, Who has placed this goal before them, has created them both for this goal, in accordance with His free and unlimited Will.”9

Assigning a goal to not just human beings, but the whole natural world, strains credulity. Is it worth denying the plain meaning of Genesis 1:2—that chaotic undifferentiation, darkness, and the mysterious deeps existed before God started creating the world—in order to defend the post-biblical belief that God is omnipotent, omniscient, and omnibenevolent?

The beginning of Genesis does not say that God created darkness. Nor does it say that darkness is evil. Darkness is just there, like God’s hovering breath. Evil does not come into the picture until after God has created humankind.

After all, we humans decide what we classify as evil.

- Some congregations read an entire Torah portion each week, while others read a third of the Torah portion on that week. (One year it is the first third, the next year it is the middle third, and the third year it is the last third.) By either system, Jewish congregations finish Deuteronomy and start Genesis again on Simchat Torah.

- In Genesis 1:2, the noun ha-aretz comes before the verb, haitah (הָיְתתָה), which is in the perfect form. This syntax is used in Biblical Hebrew to indicate the past perfect, so the correct translation is “And the earth had been …” (Richard Elliott Friedman, Commentary on the Torah, HarperCollins Publishers, New York, 2001, p. 6)

- God does not create the sun until the fourth day. However, on the fourth day God says that the purpose of the sun, moon, and stars is: “to separate the day from the night”(Genesis 1:14).

- Pseudo-Philo, Book of Biblical Antiquities, translated by Howard Jacobson, Outside the Bible, Jewish Publication Society, 2013, p. 601.

- Radak (Rabbi David Kimchi, 1160-1235), translated in www.sefaria.org.

- Israel Knohl, The Divine Symphony: The Bible’s Many Voices, The Jewish Publication Society, Philadelphia, 2003, p. 12.

- See my post Psalm 73: When Good Things Happen.

- Samson Raphael Hirsch, The Hirsch Chumash: Sefer Bereshis, English translation by Daniel Haberman, Feldheim Publishers, Jerusalem, 2002, p. 1.

- Ibid, p. 2.