“You said to me: ‘No, for a king must be king over us!’ But Y-H-V-H, your God, is your king!” (1 Samuel 12:12)

A king makes the rules and wields absolute power over his people, the prophet Samuel warns in this week’s haftarah1 reading (1 Samuel 11:14-12:22). Like other biblical prophets, Samuel insists that this role belongs only to God. Yet the Israelites demand a human king.

The government of the Israelites is decentralized and minimal until Saul becomes king in the first book of Samuel. Prophets communicate God’s laws and decrees to the people. In each town and village, respected elders meet to judge cases and interpret the laws. The general community enforces its elders’ rulings. And when an enemy threatens more than one town, the elders of the region call for a war leader to command their fighting men until the threat is over.

Occasionally a notable Israelite holds two of these positions, but never three. Moses and Samuel serve as both the prophet and the appeals judge for the Israelites,2 but neither is a war leader. Joshua is a judge and war leader, but not a prophet.3 In the book of Judges, Gideon and Yiftach are war leaders who become local judges.4

But after the Israelites ask Samuel to appoint a king, everything changes.

Samuel’s first warning

The initial reason for their request is that Samuel is preparing for retirement as the circuit judge. He appoints his two sons as judges in Beer-sheva, a town about 59 miles (95 km) south of his own home base in Ramah.

But his sons did not walk in his ways, and they were bent on following profit, and they took bribes and bent justice. So all the elders of Israel gathered together and came to Samuel at Ramah. And they said to him: “Hey! You have grown old, and your sons have not walked in your ways. Now appoint a king for us, leshaftanu, like all the nations!” (1 Samuel 8:3-5)

leshaftanu (לְשָׁפְטַנוּ) = to judge us, to govern us. (From the verb shafat, שָׁפַת.)

In other words, the elders of all the Israelite towns and villages demand a king to replace Samuel and his sons as the court of appeals. They overlook the facts that kings are also succeeded by their sons, and that kings govern through more than judging cases.

Rabbi Steinsaltz explained: “… the rule of judges is unstable and national leadership has begun in Israel … The elders did not wish to dismiss Samuel from his position, but they wanted to regularize and facilitate the continuation of a central authority. They turned to the prophet because he had the power to decide on behalf of all Israel.”5

And the matter was bad in Samuel’s eyes … and Samuel prayed to God. And God said: ‘Listen to the voice of the people … However, you must definitely warn them; and you must tell them the procedures of the king who will be king over them.” (1 Samuel 8:6-9)

The kings of other countries in the Ancient Near East, especially Egypt and Assyria, issued new laws as well as administrative decrees. They served as appeals judges, and they also enforced their own rulings. They conducted all foreign policy, including war. They funded their personal and administrative costs through taxes, and imposed corvée labor6 and military service on their people.

So Samuel tells the Israelites:

“This will be the procedure of the king who will be king over you: he will take your sons for himself, and put them in his chariots and on his horses … and to plow his plowing and to harvest his harvest, and to make his battle weapons and his chariot weapons. And he will take away your daughters for ointment-makers, and cooks, and bakers. And he will take away your fields and your vineyards and your olive groves, the best ones, and give them to his courtiers.” (1 Samuel 8:11-14)

Samuel adds that a king will also take slaves owned by the Israelites for himself, and tithe everyone’s produce and livestock.

But the people refused to pay attention to Samuel’s voice, and they said: “No! Rather, let a king be over us, and we, we too, will be like all the nations! Ushefatanu, our king, and he will go out in front of us and fight our battles!” (1 Samuel 8:19-20)

ushefatanu (וּשְׁפָטָנוּ) = and he will judge us, and he will govern us. (Also from the verb shafat.)

The people are so swept up in the idea of having their own king, one man to serve as both judge and war leader for all the tribes, that Samuel’s warning makes no impression on them. They probably cannot imagine their own king commandeering their sons and daughters, farms, slaves, and livestock. They would only have experienced these losses when a foreign king conquered part of their territory. So Samuel resigns himself to finding a king for the Israelites.

Samuel makes Saul the first king

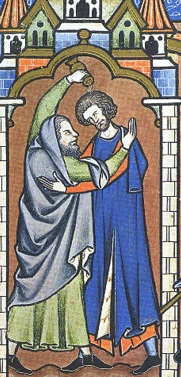

In another town on Samuel’s circuit as an appeals judge, God identifies the future king of Israel: Saul, a tall, handsome young man who has never done anything. And Samuel anoints him.7

Samuel gathers the Israelites at Mitzpah, and casts lots, knowing that God will make the lot indicate Saul. But when it does, Saul “has hidden himself among the baggage” (1 Samuel 10:22), and the elders have to haul him out to be presented.

Not everyone is enthusiastic about the new king. But when the king of Ammon threatens a town in Gilead, God inspires Saul to unite the tribes and defeat the Ammonite army. In this week’s haftarah reading, after the victory, Samuel assembles the Israelites at Gilgal for a ceremony confirming Saul’s kingship. Now all the Israelites are enthusiastic about King Saul—except for Samuel.

In this week’s haftarah, Samuel first asks the crowd whether he has ever abused his position as a circuit judge.

And they said: “You have not defrauded us, and you have not oppressed us, and you have not taken anything from anyone’s hand!” (1 Samuel 12:4)

The implication is that they do not need a king as a judge.

Next Samuel argues that the Israelites do not need a permanent war leader. In the past, he says, when Israelites needed to be rescued from enemies, God inspired someone to step forward as a temporary war leader.

“And he rescued you from your enemies all around, and you lived in security. But you saw that Nachash, king of the Ammonites, was coming against you. And you said to me: ‘No! For a king must be king over us!’ Yet God is your king. But now here is the king whom you have chosen, whom you have requested. And here, God has set a king over you!” (1 Samuel 12:11-13)

The kings of the Israelites

Later, Samuel replaces King Saul with King David, who is succeeded by his son Solomon. After King Solomon dies, the Kingdom of Israel splits into two kingdoms because Solomon’s son and successor, Rehoboam, imposes harsher corvée labor than his father.8

Yet according to the Hebrew Bible, none of the kings of the northern kingdom of Israel and the southern kingdom of Judah make the Israelites quite “like all the nations”. Although Israelite kings do issue decrees, judge cases, conduct wars and other foreign affairs, and impose taxes and obligatory labor, they do not wield absolute power. Unlike neighboring kings, they are not considered divine, and they are forbidden to interfere with the priests—or to ignore the laws in the Torah.9

The “No Kings” protests on June 14, 2025, made me wonder what Samuel would think of President Donald Trump.

(The inspiration for the “No Kings” protests included Trump’s own comment “Long live the king!” on a social media platform in February, and his deluge of executive orders that exceeded previous restraints on presidential power. The date for “No Kings” coincided with a military parade Trump had arranged. The slogan “No Kings” was also reminder of the American Revolution and the Constitutional Convention, both dedicated to the ideal of democratic self-governance.)

On laws and decrees. Samuel believed that God was the people’s true king, and that any government could not transgress God’s laws recorded in the Torah. In the United States, the constitution fills a similar function—although unlike the Torah, it can be amended. (Samuel would probably disapprove of the freedom of religion clause in the first amendment to the U.S. constitution. But he never questions freedom of speech, or the right of people to assemble and petition him.)

No one had real power to make new rules until there were kings, who issued unilateral decrees. Samuel warned that kings ruling by decree could seize family members and personal property.

The American constitution established an elected legislative branch to write new laws as needed, and an elected president to administer those laws. But in the 20th century, as Congress became increasingly impotent, presidents issued executive orders that did not just administer programs, but also initiated or effectively eliminated programs. This “imperial presidency” has reached its peak (so far) in the first part of Trump’s second term as president. I suspect Samuel would disapprove of any head of state ruling by unilateral decree, even if courtiers or lawyers justified the decrees by referring to laws written for other purposes.

On judges. In ancient Israelite territory, judges interpreted the written laws and determined whether they have been transgressed. Local judges, i.e. a court of elders in a village or town, referred difficult cases to appeals judges like Samuel. Samuel would have approved of the separate judicial branch in the U.S. constitution—especially the right of the Supreme Court to overthrow laws it deemed unconstitutional.

On enforcement. Samuel preferred the self-policing communities of the Israelites before they had a king. He did not specifically address the question of who would enforce a king’s decrees, but he denounced the seizures of human beings and personal property that he said were the typical results of those decrees.

In the United States today, municipalities, counties, and states provide police to enforce the law, but technically there is no federal police. The national guard of each state serves as a militia in the event of an emergency, and Trump recently mobilized California’s national guard over the governor’s protests. He has also expanded the policing authority of ICE, the U.S. Immigration and Customs Authority. Samuel would have denounced both moves as the unethical actions of a king.

On war and foreign policy. Samuel advocated for the old Israelite custom that in the event of a war, the elders of collaborating towns would call for a volunteer general, and the communities would muster their own soldiers. Samuel warned against setting up a permanent war leader, and he accused kings of drafting soldiers. He would have denounced the clause in Article 2 of the U.S. constitution, which makes the president the commander in chief of all the armed forces.

He would have had a more favorable opinion of the clauses in Article 1 of the constitution that assign Congress the right to declare war and to regulate commerce with foreign nations.

But the delay in declaring war became unwieldy in the mid-20th century, and presidents began issuing executive orders to engage in military actions—wars in all but name. This year, President Trump has executed a military action against Iran, as well as ordering tariffs on goods from foreign nations. Samuel would consider these the actions of a king.

The only kings today are constitutional monarchs with ceremonial roles, so “king” has become a friendlier word. People who have the powers of Ancient Near Eastern kings are called autocrats instead. Some autocrats begin their careers with an election. But then they take the law into their own hands, like the ancient kings, and deprive people of their customary rights and freedoms. Voters do not always know who will turn out to be an autocrat.

At this point, Samuel would probably consider President Trump a king.

- The haftarah is the weekly reading from the Prophets that accompanies the Torah portion. This week’s Torah portion is Korach in the book of Numbers.

- Samuel is a circuit-court judge who travels from town to town judging cases that the elders cannot resolve (1 Samuel 7:15-17). However, Deuteronomy 17:8-9 decrees that in the future, when a town’s elders cannot reach a verdict, they must take the case to the priests or appointed judge at the yet-to-be-built temple. This temple is built by King Solomon in 1 Kings.

- The high priest uses lots and magical devices to interpret God’s desires in the book of Joshua.

- Judges 6-8, 11.

- Rabbi Adin Even-Israel Steinsaltz, Introductions to Tanakh, I Samuel, reprinted in www.sefaria.org.

- Corvée labor is unpaid, forced labor imposed by the government on some of its residents for a fixed period of time. The pharaohs in the book of Exodus imposed a corvée on the Israelites then extended the time period indefinitely.

- 1 Samuel 9:1-21.

- 1 Kings 12:1-20.

- Deuteronomy 17:19-20.

One thought on “Haftarat Korach—1 Samuel: No Kings?”