(This is my eleventh post in a series about the conversations between Moses and God, and how their relationship evolves in the book of Exodus/Shemot. If you would like to read one of my posts about this week’s Torah portion, Vayikra, the first in the book of Leviticus/Vayikra, you might try: Vayikra: A Voice Calling.)

On top of Mount Sinai, God gives Moses a pair of stone tablets engraved with laws, and detailed instructions for making a portable tent-sanctuary. At the foot of the mountain, the Israelites despair of seeing Moses again, and start worshiping a Golden Calf. God offers to exterminate the people and start over with Moses’ descendants, but Moses remains loyal to the Israelites. Then Moses goes down and smashes God’s stone tablets without permission, but God takes no action against him. The working relationship between the two leaders, human and divine, seems strong. (See my post: Ki Tisa: Taking Risks.)

Moses, citing an order from God, arranges the massacre of 3,000 Israelites who are presumed to be the worst of the Golden Calf worshipers.1

Then it was the next day, and Moses said to the people: “You, you are guilty of a great guilt! And now, I will go up to Y-H-V-H. Perhaps akhaprah [with God] on behalf of your guilt.” (Exodus 32:30)

akhaprah (אֲכַפְּרָה) = I may make atonement, appease, effect reconciliation.

Moses does not want the surviving Israelites to think they are in the clear, so he reminds them that they, too, bear some guilt, even those who passively stood by while others engaged in calf worship. But he also wants God to forgive the surviving Israelites, so he tries to get God to commit to a general pardon.

Forgive them or erase me

Then Moses returned to Y-H-V-H and said: “Please, this people is guilty of a great guilt; they made themselves a god of gold! And now, if you would lift their guilt— But if not, erase me, please, from the book katavta!” (Exodus 32:31-32)

katavta (כָּתָבְתָּ) = you have written, you have engraved words on.

According to Rashi, “the book you have written” means “the entire book of the Torah” and the reason Moses asked to be erased from it is “that people should not say about me that I was not worthy enough to pray effectively for them.”2

Yet in the Hebrew Bible, the only part of the Torah that God writes directly (instead of dictating to Moses) is whatever God engraves on the two stone tablets (according to Deuteronomy 5:19, the Ten Words or Ten Commandments).

Other commentators have identified “the book you have written” with “the book of life” in Psalm 69.3 Praying for the downfall of his enemies, the psalmist begs God:

“Erase them from the bookof life, and do not inscribe them among the righteous!” (Psalm 69:29)

Many psalms assume that God grants health and long life to the righteous, but Psalm 69 is the only one in which God keeps a (perhaps metaphorical) account book.4

So Moses is asking God to either pardon the Israelites, or give him death. I suspect he hopes that God will quickly opt to preserve the life of God’s favorite prophet, and issue a pardon.

According to Or HaChayim, “… it is one of God’s virtues that He cannot tolerate seeing His righteous people, His ‘friends,’ suffer pain. Accordingly, how could God inflict the pain of destroying His people on Moses? Surely God was perfectly aware of how Moses would grieve over the destruction of his people!”5

Yet God’s reply indicates that he does not fall for Moses’ either-or statement.

And Y-H-V-H said to Moses: “Whoever is guilty against me, I will erase from my book. And now go, lead the people to where I have spoken to you! Hey, my messenger will go before you. But on the day of my accounting, I will call them to account over their guilt.” (Exodus 32:33-34)

God is not about to erase Moses, who is innocent. But God refuses to declare a blanket pardon for the surviving Israelites.

When is the day of God’s accounting? Every day, according to a commentary in Yiddish: “The Holy One said: I will forgive the sin. However, I will make Israel pay for the sin a little at a time. No trouble comes upon Israel that is not related to the Golden Calf. That is to say, the Holy One repays Israel for the sin of the Golden Calf all the time.”6

Or perhaps God’s day of accounting is the day of a plague in the next verse of Exodus:

And Y-H-V-H struck the people with plague over what they did with the calf that Aaron made. (Exodus 32:35) The text does not say how many people die in this plague, but it certainly counts as a punishment.

Let me know your ways

Then Y-H-V-H spoke to Moses: “Go up from here, you and the people whom you brought up from Egypt! … I will not go up in your midst—because you are a stiff-necked people—lest I consume you on the way.” (Exodus 33:1, 3)

Now God says Moses brought up the people from Egypt, making him responsible even though it was God’s idea in the first place, and it never would have happened without God’s persistence and miracles. God also seems to be ordering an immediate departure from Mount Sinai, even though the people have not constructed the tent-sanctuary God requested so that God could “dwell among them” (Exodus 25:8).

Furthermore, God decides not to dwell among the Israelites as they travel, because God is so angry already that when the stubborn Israelites violate the rules again, God will “consume” them. (This God character is located in only one place at a time.)

The Israelites mourn over the news that God will not go with them. But Moses is determined to get God to both pardon them and travel in their midst. He tries a different tactic, saying:

“And now, please, if I have found favor in your eyes, please let me know your ways! Then I will know you—so that I can find favor in your eyes. And see that your people is this people!” (Exodus 33:13)

Moses asks to learn God’s ways so that he can continue to please God in the future. He does not mention that if he knows how to please God, he can bargain more effectively for God’s pardon and presence.

Rabbi Steinsaltz, however, assigned Moses an additional motivation: “Moses requested a deeper relationship with God than he had attained thus far. Until this point, he had mainly received instructions. Now Moses desired the secret knowledge that would enable him to achieve communion with God, as one’s closeness to God is related to the extent of his knowledge of the Divine.”7

Moses follows up his polite request to know God’s ways with an imperative: “See that your people is this people!” God must admit ownership of the Israelites. They would not be in the wilderness of Sinai if it were not for God, and they will feel abandoned if God’s presence is not with them.8

And [God] said: “[If] my panim goes [with you], will I make you rest easy?” (Exodus 33:14)

Moses exclaims:

“If your panim is not going, don’t bring us up from here!” (Exodus 33:15)

panim (פָּנִים) = face; front surface; presence.

He adds a rationale that he hopes will sway God.

“And how is it to be known, then, that I have found favor in your eyes, I and your people? Isn’t it in your going with us? Then we are distinct, I and your people, from all the people that are on the panim of the earth.” (Exodus 33:16)

And Y-H-V-H said to Moses: “Indeed, this word that you have spoken, I will do, since you have found favor in my eyes, and I know you by name.” (Exodus 33:17)

It is not clear which “word” God is promising to do: to go in the midst of the Israelites, or to let Moses know God’s ways. At this point Moses decides to press his request to learn God’s ways.

Then [Moses] said: “Please let me see your kavod!” (Exodus 33:18)

kavod (כָּבוֹד) = impressiveness, honor, splendor, glory.

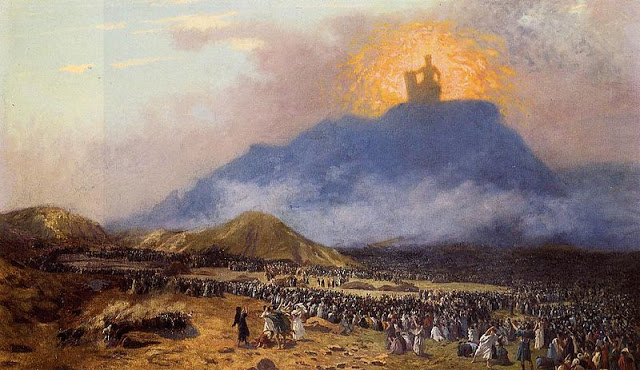

All the Israelites have seen the kavod of God as a fire at the top of Mount Sinai, which looked like a cloud to Moses.9 But Moses is asking to see more. According to Chizkuni, “Moses asked for a visual appearance of God’s essence.”10 But according to Rabbi Hirsch, “The perception he now seeks is on a higher level, that of intuition.”11

And [God] said: “I, I will cause all my goodness to pass in front of your panim, and I will call out the name of Y-H-V-H in front of your panim. But … you will not be able to see my panim, because a human cannot see me and live.” (Exodus 33:19-20)

Here panim means “face”. Moses’ face is where his physical organs for seeing and hearing are located (if we count ears as part of a human face). God’s face is unknowable.

“… as my kavod passes by, I will place you in a crevice of the rock, and screen you with my hand until I have passed by. Then I will take away my hand, and you will see the back side of me. But my panim will not be seen.” (Exodus 33:22-23)

Next God grants an additional favor that Moses has not asked for.

And Y-H-V-H said to Moses: “Carve yourself two stone tablets like the first ones, and I will inscribe on the tablets the words that were on the first tablets, which you smashed.” (Exodus 34:1)

The first time, God provided the completed tablets. Now God tells Moses to carve stone blanks, which God will inscribe. Abarbanel explained: “For it was Moses’ obligation, since he destroyed the first set of tablets … And the reason for the word ‘yourself’ was to warn Moses that he himself, and no other, should carve the tablets.”12

Moses carries two blank stone tablets up Mount Sinai early the next morning. God comes down in a cloud, and as “the back side” of God passes Moses, Moses perceives some of God’s qualities. Either God or Moses calls out:

“Y-H-V-H! Y-H-V-H! Mighty-one, compassionate and gracious, long-nosed [slow to anger], abundant in loyal-kindness and reliability, keeping loyal-kindness to the thousandth [generation], lifting away crookedness and transgression and wrong-doing, and clearing [the guilty]!” (Exodus 34:6-7)

This list is called “The Thirteen Attributes of Mercy”, which are still chanted at services on Jewish holy days. (Most commentators reach thirteen by counting the second “Y-H-V-H” as a different attribute from the first.) Rashbam noted that each of these thirteen “is of relevance when inducing forgiveness and repentance.”13 Since Moses wants God to forgive the Israelites, this insight would be encouraging.

Is the compassionate god in this description the same deity who killed thousands of innocent Egyptians without a second thought in the tenth miraculous plague, the death of the firstborn? Is this the god who would angrily “consume” the stiff-necked Israelites along the way to Canaan?

Perhaps the God character has decided to become more compassionate and kind, and is giving an aspirational self-description. Moses seizes the moment to repeat his request.

And Moses hurried and bowed to the ground and prostrated himself. And he said: “Please, if I have found favor in your eyes, my lord, please may my lord go among us! Indeed, it is a stiff-necked people. So forgive our crookedness and our wrong-doing, and make us your possession!” (Exodus 34:8-9)

Moses identifies himself as one of the Israelites, begging God to forgive and accept “us”.

Commentator Jerome Segal detected an additional strategy in Moses’ plea. What if God’s anger overwhelms God’s compassion? “Thus, it appears that Moses prevailed upon God to be in their midst just so he would be able to argue, should the eventuality arise, that God is too closely identified with the Israelites to destroy them. In short, Moses emerges as a canny strategist, subtly manipulating the powerful but less crafty deity.”14

A year or so later, God is indeed ready to wipe out the Israelites, and Moses persuades God to refrain with an argument along those lines.15

An ambiguous answer

After Moses has asked God again to “go among us” and forgive the Israelites, God says:

“Hey, I myself will be cutting a covenant: in front of all your people I will do wonders that were not created on all the earth or among all the nations. Then they will see, all the people in whose midst you are, the deeds of Y-H-V-H—that it is awesome what I myself do with you.” (Exodus 34:10)

Once again, God calls the Israelites Moses’ people, not God’s own people. And once again, God’s response is favorable but avoids addressing Moses’ request directly. Instead, God tries to resolve the whole issue with a new covenant. The terms are that God will perform more wonders for the Israelites, through Moses. In return, the Israelites will obey the commandments on the stone tablets, along with some other rules that God dictates to Moses on the spot.

Moses has to assume that God has forgiven the Israelites, and that the new covenant means God will dwell among them after all.

Moses and God respect one another, but Moses resorts to wheedling and subterfuge—because God refuses to make definite commitments. Their relationship has become like an unhealthy marriage.

To be continued …

- Exodus 32:25-28. See my post: Ki Tisa: Golden Calf, Stone Commandments.

- Rashi (11th-century Rabbi Shlomoh Yitzchaki), translation in www.sefaria.org.

- E.g. Talmud Bavli, Rosh Hashanah 16b; Rashbam (12th-century Rabbi Shmuel ben Meir), Chizkuni (a 13th century collection), Tur HaArokh (14th century), Or HaChayim (by 18th century rabbi Chayim ibn Attar).

- In Talmud Bavli, Rosh Hashanah 16b, God writes down the names of the righteous in one book and the names of the wicked in another. People whose deeds are partly good and partly bad are listed in a third book until Yom Kippur, ten days later, when God decides which of these intermediate people to record with the righteous in the book of life. To this day, the Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur liturgy includes prayers to be written in God’s “book of life” so we will not die before the next Rosh Hashanah.

- Or HaChayim (18th century), by Rabbi Chayim bin Attar, translation in www.sefaria.org.

- Tze-enah Ure-enah (17th century), translation in www.sefaria.org.

- Rabbi Adin Even-Israel Steinsaltz, The Steinsaltz Tanakh, Koren Publishers, Jerusalem, 2019, quoted in www.sefaria.org.

- This may be a misunderstanding. What if the Israelites only want the manifestation of God as the column of cloud by day and fire by night that led them from Egypt to Mount Sinai? God might consider that a divine messenger. When the Israelites leave Mount Sinai, the column appears again to lead them, and when God is dwelling among them in the tent-sanctuary, cloud and fire appear over its roof.

- Exodus 24:16-17.

- Chizkuni, a 13th-century collection of commentary, translation in www.sefaria.org.

- Rabbi Samon Raphael Hirsch (19th century), The Hirsch Chumash: Sefer Shemos, translated by Daniel Haberman, Feldheim Publishers, Jerusalem, 2005, p. 794.

- Isaac ben Judah Abarbanel (15th century commentator), translation in www.sefaria.org.

- Rashbam (12th-century Rabbi Shmuel ben Meier), translation in www.sefaria.org.

- Jerome M. Segal, Joseph’s Bones, Riverhead Books, New York, 2007, p. 134-135.

- Numbers 14:11-20.

One thought on “Ki Tisa: Seeking a Pardon”