(This is my tenth post in a series about the evolving relationship between Moses and God in the book of Exodus/Shemot. If you would like to read one of my posts about this week’s Torah portion, Pekudei, you might try: Pekudei: Clouds of Glory.)

After Moses has orchestrated four covenants between God and the Israelites (see my post: Yitro & Mishpatim: Four Attempts at a Lasting Covenant), God tells him:

“Go up to me on the mountain and be there, and I will give you the stone tablets and the teaching and the command that I have written to teach them.” (Exodus 24:12)

Moses spends 40 days and 40 nights on top of Mount Sinai, listening to God tell him how to set up a formal religion for the Israelites, from the portable sanctuary-tent to the gold-plated ark to the ordination of Aaron and his four sons as priests.

Only at the end of the 40-day period does God give Moses any stone tablets.

Then [God] gave to Moses, when [God] finished speaking with him on Mount Sinai, the two tablets of the Testimony, tablets of stone engraved by the finger of God. (Exodus 31:18)

Meanwhile, in the camp at the foot of the mountain, the Israelites despair of ever seeing Moses again.

… and the people assembled against Aaron and said to him: “Get up, make us a god who will go before us! Because this Moses, the man who brought us up from the land of Egypt, we do not know what has become of him!” (Exodus 32:1)

Blame game

Moses has no idea that the Israelites are worshipping a golden calf below. After giving Moses the stone tablets, God breaks the news to him.

Then Y-H-V-H said to Moses: “Go, get down! For your people whom you brought up from the land of Egypt have become corrupt! They have quickly turned away from the path that I commanded them; they made themselves a cast-metal calf, and they bowed down to it, and they sacrificed to it, and they said: ‘These are your gods, Israel, who brought you up from the land of Egypt’!” (Exodus 32:7-8)

First God says the calf-worshipers are Moses’ people whom Moses brought up from Egypt. Then God notes that they are calling the Golden Calf their gods who brought them up from Egypt.

Yet God was the one who noticed the suffering of the Israelites, recruited and trained Moses, created the ten miraculous plagues in Egypt, led the Israelites with a column of cloud and fire, split the Reed Sea, and fed them manna in the wilderness. God told Moses:

“And I will bring out my ranks, my people the Israelites, from the land of Egypt …” (Exodus 7:4)

But now God seems to be disowning the people and the whole enterprise.

Rashi1 and earlier commentators claimed that the people whom God calls “your people” are not all the people, but only the non-Israelites who chose to leave Egypt with the Israelites. In this reading, the non-Israelites are Moses’ people because Moses converted them. And the non-Israelite converts are the ones who corrupted the “real” Israelites and persuaded them to demand an idol. (Like most humans, the classic commentators were not exempt from xenophobia.) The Torah itself does say that an erev rav—mixed multitude or riff-raff—joined the Israelites,2 but it never says Moses converted them.

To me it seems more likely that the God character says “your people” as a way to pass the buck for the people’s violation of the divine rules. Alternatively, the God character is pretending to assign the blame to Moses in order to see how he will respond.

Moses tosses the blame back at God. After God tells Moses about the Golden Calf, Moses says:

“Why, Y-H-V-H, should your nose burn against your people, whom you brought out from the land of Egypt with great power and a strong hand?” (Exodus 32:11)

(A burning nose is a biblical idiom for anger.)

Moses is confident enough to pass the buck back to God, and God lets it go and moves on to the important item on God’s agenda: making Moses an offer he can refuse.

Taking a risk with Moses

And Y-H-V-H said to Moses: “I have observed this people, and hey! It is a stiff-necked people. And now, hanichah me, and my nose will burn against them, and I will exterminate them! And I will make you into a great nation.” (Exodus 32:9-10)

hanichah (הַנִּיחָה) = allow, leave alone. (Imperative of the hifil form of nach, נעָה = rest, settle, wait.)

It sounds as if God is ready to give up on the Israelites, eliminate them, and start over with Moses’s descendants, who presumably would someday rule Canaan. But first God wants Moses’ permission.

Is God serious? One possibility is that God is asking Moses as a courtesy, but is determined to exterminate the Israelites no matter what Moses says. This is unlikely, however, since Moses has become a full partner in leadership, and would not agree with God the way a subordinate says yes to curry favor.

Another possibility is that God really is leaving the decision up to Moses. According to the Talmud, “Moses said to himself: If God is telling me to let Him be, it must be because this matter is dependent upon me. Immediately Moses stood and was strengthened in prayer, and asked that God have mercy on the nation of Israel and forgive them for their transgression.”3

But it is hard to believe that God has no strong preference. A few hundred years before, God promised Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob that their descendants would rule the land of Canaan. Recently God created ten miraculous plagues that ruined Egypt. The Israelites have become God’s people as much as Moses has become God’s prophet. It seems unlikely that God would discard them and wait another four hundred years until Moses’s descendants had multiplied enough to occupy Canaan.

A third possibility is that God intends to give the Israelites a sharp lesson without abandoning them altogether—but also wants to find out what Moses would choose. After all, God tests Abraham in the book of Genesis by ordering him to slaughter his son Isaac as an offering, and then calls him off at the last minute.4 Now God seems to be testing Moses.

Then Moses softened the face of Y-H-V-H, his god, and he said: “Why, Y-H-V-H, should your nose burn against your people, whom you brought out from the land of Egypt with great power and a strong hand?” (Exodus 32:11)

In order to “soften the face” of God, i.e. reduce the God character’s anger, Moses reminds God of how much God has invested in the Israelites. Next he gives one of the reasons that God went to all that trouble: to prove to the Egyptians that they had better not mess around with a people God chooses to deliver.

“Why should the Egyptians actually [be able to] say: ‘In evil he brought them out, to kill them in the mountains, and to exterminate them from the face of the earth’? Turn away from your burning nose, and hinacheim about the evil against your people!” (Exodus 32:12)

hinacheim (הִנָּחֵם) = have a change of heart; regret, repent, or find consolation. (From the verb nacham, נָחַם.)

Moses knows God wanted to establish a reputation as more powerful than any Egyptian god because God told Moses to pass on these words to the pharaoh before the plague of hail:

“Indeed, on account of this I let you stand: so that you would see my power, and for the sake of recounting my name throughout all the land!” (Exodus 9:16)

In case all this is not enough to persuade God to refrain from wiping out the Israelites, Moses offers a third argument:

“Remember Abraham, Isaac, and Israel, your servants, whom you yourself swore to when you spoke to them: ‘I will multiply your seed like the stars in the heavens, and all this land that I said, I will give to your seed, they will inherit it forever.” (Exodus 32:13)

Here Moses is insisting that God must keep promises. This argument is not as convincing, since Moses himself belongs to the tribe of Levi and is a “seed” of Abraham, Isaac, and Israel, a.k.a. Jacob. God’s promise could still be fulfilled through Moses’ descendants, although it would take several hundred more years.

But I suspect that the content of Moses’ arguments does not matter. God’s motivation is to test Moses and find out if he will stick up for the Israelites, instead of pursuing his own glory as the founding ancestor of a nation. And Moses passes the test without hesitating for a moment, by arguing against eliminating the Israelites.

Vayinachem, Y-H-V-H, about the evil that [God] had spoken of doing to [God’s] people. (Exodus 32:14)

vayinachem (וַיִּנָּחֶם) = and he had a change of heart; regretted, repented, consoled himself. (Also from the root verb nach.)

From Moses’ point of view, God has a change of heart and therefore rescinds the plan to wipe out the Israelites. The text does not tell us the God character’s point of view. But I think God takes a risk by tempting Moses with an easier path to fame, something he could achieve simply by going home to Midian and having more children. God knows Moses never wanted to be in charge of thousands of frightened, stubborn, and wayward ex-slaves.

Taking a risk with God

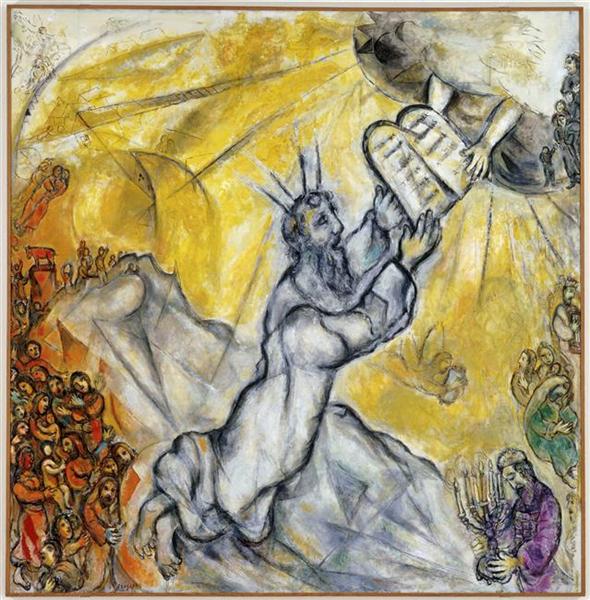

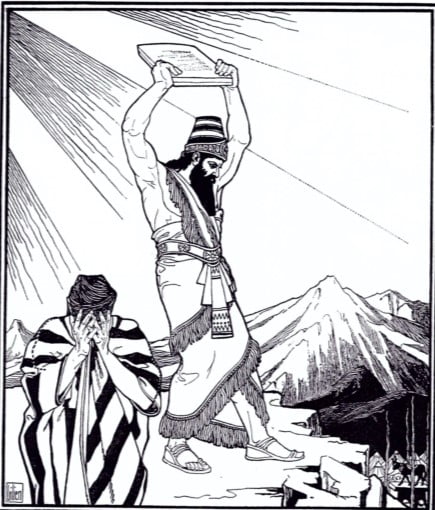

Moses turns around and walks down the mountain, carrying the two stone tablets engraved by God. The text emphasizes the divine origin of the tablets, saying:

And the tablets, they were God’s making. And the writing, it was the writing of God, engraved on the tablets. (Exodus 32:16)

What could be more precious and holy?

Then it happened, as he approached the camp and he saw the calf and the dancing. And Moses’ nose burned, and he threw the tablets from his hands, and he shattered them at the bottom of the mountain. (Exodus 32:19)

The text implies that Moses acts in anger, as God had threatened to do. But much of the commentary assumes that whatever his mood, Moses is not throwing a temper tantrum, but rather acting on a flash of insight.

According to the midrash Shemot Rabbah, “he saw that Israel would not survive, and he joined himself with them and broke the tablets. He said to the Holy One blessed be He: ‘They sinned and I sinned, as I broke the tablets. … if You do not pardon them, do not pardon me …”5

According to 12th-century commentator Ibn Ezra, the stone tablets “served, as it were, as a document of witness. Moses thus tore up the contract.”6 (Ibn Ezra considered the stone tablets a contract document because according to Deuteronomy 5:19, God uttered the “Ten Commandments” and later engraved them on the stone tablets. One of these commandments prohibits making or worshiping idols. In Exodus 24:3, Moses told the people all the rules God had handed down, including the “Ten Commandments”, and the Israelites vowed: “All the words that God has spoken, we will do!” 7)

And according to 19th-century commentator Hirsch, when Moses saw the dancing, “he realized that the pagan error had already borne its usual fruit—the unleashing of sensuality. He then understood that the nation would have to be re-educated … By this act he declared in no uncertain terms that the people in its present state was unworthy of the Torah and not fit to receive it.”8

Whatever Moses’ insight is, he risks retribution from God when he shatters God’s words carved in stone. By taking this risk, he joins his fate to the fate of the people (Shemot Rabbah), shatters the evidence of the covenant so the Israelites are not technically guilty of violating it (Ibn Ezra), and sets himself the task of teaching the Israelites how to behave (Hirsch).

And the risk pays off. God never questions Moses’ dramatic action. The two leaders, Moses and God, work together to punish the Israelites for the Golden Calf.

To be continued …

- Rashi is the acronym of 11th-century Rabbi Shlomoh Yitzchaki.

- Exodus 12:38.

- Talmud Bavli, Berakhot 32a, William Davidson translation, from www.sefaria.org.

- Genesis 22.

- Shemot Rabbah 46:1 (10th-12th century midrash), translation in www.sefaria.org.

- Rabbi Abraham ibn Ezra, translation in www.sefaria.org.

- See my post: Yitro & Mishpatim: Four Attempts at a Lasting Covenant.

- Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch, the Hirsch Chumash: Sefer Shemos, translated by Daniel Haberman, Feldheim Publishers, Jerusalem, 2005, p. 770.

2 thoughts on “Ki Tisa: Taking Risks”