(This is the fourth post in a series about the conversations between Moses and Gold on Mount Sinai (a.k.a. Choreiv), and how their relationship evolves. If you would like to read one of my posts about this week’s Torah portion, Yitro, you might try: Yitro: Rejected Wife.)

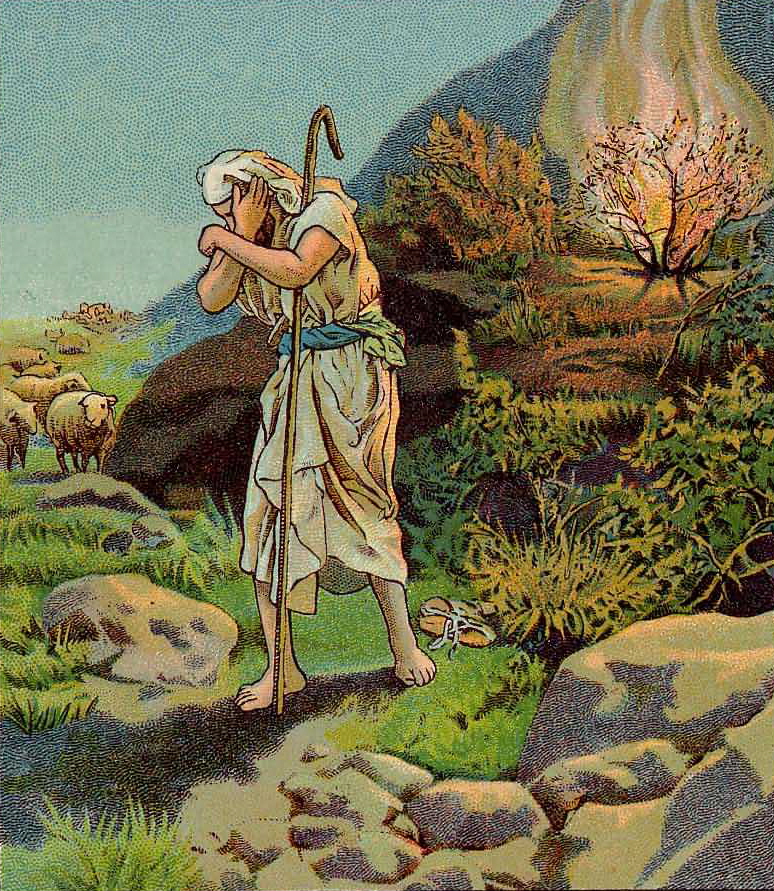

Speaking out of the fire in the thornbush, God tells Moses the plan for bringing the Israelites out of Egypt and into Canaan, and concludes:

“And now, come! And I will send you to Pharaoh, and you will bring out my people, the Israelites, from Egypt.” (Exodus 3:10)

Moses immediately begins trying to excuse himself from the mission. But God has an answer to each of his first three objections. God even equips Moses with two miraculous signs he can demonstrate to the Israelites so they will believe their god sent him. (See my posts: Shemot: Empathy, Fear, and Humility and Shemot: Names and Miracles.)

But Moses makes a fourth objection: he can hardly speak at all. His implication is that someone who cannot make himself understood to either the Israelites or Pharaoh would be a poor agent for God.

And Moses said to Y-H-V-H: “Please excuse me, my lord; I am not a man of words, neither in the past, nor the day before yesterday, nor at the time when you speak to your servant [now]—because I am heavy of mouth and heavy of tongue.” (Exodus 4:10)

(The Hebrew word for “heavy”, kavod, כָּבוֹד, can also mean impressive, magnificent, or glorious, but only the primary meaning, “heavy”, fits this verse. Less literal English translations of Exodus 4:10 change the metaphor from “heavy” to “slow”.)

What does Moses mean when he says he is heavy of mouth and tongue, and therefore not a man of words? One opinion is that Moses has a speech defect, while another line of commentary says he has no trouble with pronunciation, but he cannot find the right words.

Defective pronunciation?

The speech defect camp includes Rashi (11th-century rabbi Shlomoh Yitzchaki), who wrote that Moses is a stammerer; and 12th-century rabbi Abraham ibn Ezra, who argued that Moses could not pronounce any of the labials (consonants pronounced with the lips, such as בּ (b) and פּ (p)), and also had trouble with some of the linguals (consonants pronounced with the tongue, such as ד (d), and ל (l)).

The classic midrash invented an episode in Moses’ childhood to account for a speech defect. When Moses was weaned, he was adopted as a son by the pharaoh’s daughter.1 In one version of the midrash, “Pharaoh would kiss him and hug him, and he would take Pharaoh’s crown and place it on his head, as he was destined to do when he grew older. … The magicians of Egypt were sitting there, and said: ‘We are afraid of this one who takes your crown and places it on his head, lest he be the one regarding whom we said that he is destined to wrest your kingdom from you.’ Some of them said to behead him, some said to burn him.” (Shemot Rabbah)2

In another version, “While growing up in Pharaoh’s palace Moses once took the king’s crown and threw it on the ground. The king wanted to execute him on account of this misdemeanor.” (Rabbeinu Bachya’s paraphrase of Pesikta Zutrata)3

In both versions of the midrash, little Moses was presented with a bowl containing a lump of gold and a burning coal. The court agrees that if he reached for the gold, he was smart enough to depose the pharaoh when he grew up, and he would be executed. But if he reached for the coal, he would be allowed to live.

“Immediately, they brought it before him and he extended his hand to take the gold. [The angel] Gabriel came and pushed his hand. He seized the coal and placed his hand with the coal into his mouth, and his tongue was burned.” (Shemot Rabbah)4

And God said to him: “Who placed a mouth in the human being? Or who makes [someone] mute or deaf or clear-sighted or blind? Is it not I, God? So now go! And I myself will be with your mouth, and I will instruct you regarding what you will speak.” (Exodus 4:11-12)

The first part of God’s rebuttal supports the speech defect theory; it implies that God is responsible for all the physical characteristics a person is born with, including birth defects. But then why does God promise to “instruct” Moses regarding what to say?

Ibn Ezra wrote: “God told Moses that He would teach him to speak with words that do not contain letters that he had difficulty enunciating.”5 Other commentators wrote that whenever Moses was speaking as God’s agent, God would intervene so that Moses’ lips and tongue would operate perfectly.

According to the 14th-century commentary Tur HaArokh, God “simply told him to go and fulfill his mission, and that He would come to his aid whenever required. Whatever he would be saying to Pharaoh would come out of his mouth clear …”6

19th-century Rabbi S.R. Hirsch added: “In fact, a stammerer is he most fitting one to carry out this mission. Every word that he will utter will itself be a sign. If a man who ordinarily stammers is able to speak fluently when he speaks at God’s command, his every word bears the stamp of credibility.”7

Why doesn’t God eliminate Moses’ speech defect altogether? Because Moses does not ask him to, according to the commentators who favor the speech defect theory. And why doesn’t Moses pray to God to remove his speech defect?

“Seeing that Moses, basically, did not wish to assume the burden of leadership at all, he did not pray to God to heal his speech defect. He contented himself with saying that someone with a blemish such as he suffered from was not likely to be the most suitable candidate for the task proposed by God. God, for His part, did not want to heal his speech defect precisely because he had not prayed to Him to do this.” (Tur HaArokh) 8

At a loss for words?

Other commentary rejects the theory that Moses has a speech defect, and interprets his statement that he is “not a man of words” as an argument that he is not a persuasive speaker. Being “heavy of mouth and heavy of tongue” is then a metaphor for a general delay in finding the right words to say. A 2nd-century C.E. commentary simply states that Moses is not eloquent.9

A millennium later, Rashbam and Chizkuni10 claimed that Moses fled from Egypt before he had completed his education, and has not spoken the Egyptian language since, so therefore he is not fluent in the language spoken by the Egyptian aristocracy.11

Yet Moses grew up with an Egyptian princess as his adoptive mother; he must have been exposed to upper-class Egyptian for years. I suspect Moses is more likely to worry that he will be unable to speak in Hebrew to the Israelites living in Egypt. After all, when he was weaned (at around age three in that culture) the pharaoh’s daughter adopted him, and he left his Israelite birth parents. Only when Moses became an adult did he go to see the people of his birth.

… and Moses grew up. And he went out to his kinsmen, and he saw their forced labor. And he saw an Egyptian man striking a Hebrew man, one of his kinsmen. And he turned this way and that way, and he saw that there was no man, and he struck down the Egyptian and buried him in the sand. (Exodus 2:11-12)

If Moses had not led a sheltered and insulated life in the palace, he would know that the Israelites doing forced labor on the pharaoh’s building projects were often beaten12—and he would know that killing one overseer would not rescue any Israelite from future beatings.

Instead, Moses might well think he can rescue the victim and eliminate the oppressor himself, as long as he kills the overseer in secret.13 But his secret is revealed, and the pharaoh, Moses’ adoptive grandfather, orders him killed. Apparently the society Moses has grown up in has no qualms about summary executions.

Tammi J. Schneider noted in a 2025 article: “Moses does not, however, have a conversation with the Egyptian about his actions before he kills him. Moses is a bit of a hothead. The next day, when Moses finds two Hebrews fighting, he does speak briefly with the offender. The text is silent as to what language they speak, but there is no suggestion that Moses has difficulty doing so … The interaction leads Moses to flee, again with no suggestion that he discussed his plan or actions with anyone; he just acts on his own impulses …

In Midian, he impulsively, without any conversation, drives off the shepherds who are preventing the seven daughters of Reuel from watering their flocks … This pattern suggests that Moses’ problem is not a speech impediment, but an impulse to act before speaking.”14 Perhaps when Moses is speaking to God on Mount Sinai, he says he is “not a man of words” because he knows he is an impulsive hothead. But there is another possible reason why he does not stop to speak before he acts.

No time for an introvert

While extraverts can think while they speak, introverts need time to figure out what they will say before they start speaking. I am an introvert, and I often want to contribute to a conversation among several people, but by the time I have composed my comment, the conversation has already moved on to another topic. Introverts can only speak well spontaneously about our own areas of expertise. The other situation in which we can speak quickly is when we happen to have rehearsed a remark ahead of time just in case the topic came up.

Many introverts do not trust themselves to come up with the right words before someone else jumps in (with either speech or action). What if Moses is an introvert, but he feels compelled to do something about the abusive overseer before any witness arrives at the scene?

He acts without speaking then. When he goes out to the worksite again the next day, he says to an Israelite who hits another Israelite: “Why do you hit your fellow?” (Exodus 2:13)

(His question is only three words long in Hebrew: “Lamah takeh rei-ekha?” (לָמָּה תַכֶּה רֵעֶךָ).)

Because the stakes are lower, Moses is willing to risk blurting something with no time to think. The guilty Israelite (an obvious extravert) taunts him by saying: “Who made you the man who is an officer and a judge over us? Are you saying you’ll kill me like you killed the Egyptian?” (Exodus 2:14) Moses turns away in silence, unable to formulate a quick rejoinder.

One advantage introverts have over extraverts is that we can happily spend long periods of time alone. When Moses flees Egypt, he does not take any servants with him, but walks alone across the wilderness of the Sinai Peninsula and into Midianite territory.

When he stops at a well there, seven sisters arrive and begin to water their flock, and then some male shepherds show up and rudely drive them away from the well. I think Moses wants to stop the men immediately, but he cannot think of what to say. So he just jumps up and drives them away. The father of the young women takes in Moses and gives him one of his daughters in marriage.

And Moses the introvert is content to shepherd his Midianite father-in-law’s flock alone in the wilderness. Once he takes the flock all the way to Mount Sinai, and God speaks to him out of a fire in a bush.

Naturally Moses is reluctant to abandon his peaceful life and afraid to return to Egypt—especially on a mission that will require him to speak to a lot of strangers about critical matters. So he tries to convince God that he is not the right man for the job. But he does not dare keep God waiting while he formulates excuses.

No wonder the four objections Moses the introvert makes are disorganized and indirect.

First Moses asks: “Who am I that I should go to Pharaoh and that I should bring out the Israelites from Egypt?” (Exodus 3:11) He pauses, perhaps searching for more words, and God promises to be with him so he will succeed.

Moses asks a second question: “And they say to me: ‘What is his name?’ What should I say to them?” (Exodus 3:13) He probably means that he does not even know the name the Israelites in Egypt use for their god. But God dips into theology and gives him two divine names related to the verb “to be” or “to become”. Then Moses manages to give the reason why he asked for a name: “But they will not trust me, and they will not pay attention to my voice.” (Exodus 4:1) In response, God patiently gives Moses two minor miracles he can perform again in Egypt.

But Moses is still afraid of returning to Egypt, and afraid that he will not be able to handle the job. So he grasps at a fourth excuse, reminding God that he is not a man of words.

If Moses had had enough time to plan his speech to God, he could have made a more coherent and convincing argument. He might have said (without pausing to let God interrupt): “But if I went, nobody would believe me! The Israelites wouldn’t believe me and follow me because I don’t speak Hebrew! And the new pharaoh wouldn’t believe me and let the Israelites go because the old pharaoh laid a murder charge on me and I ran away! So please send someone else!”

However, even if God had given Moses lots of time to figure out what to say, and he had then presented God with the argument above, it would not have let him off the hook. God would still have promised him success, still have given him two small miracles to induce the Israelites to believe him, and still have promised to feed him the right words.

And Moses, still not reassured, would still have resorted to begging God to send someone else.

To be continued …

- Exodus 2:1-10.

- Shemot Rabbah 1:26, translation in www.sefaria.org.

- 14th-century rabbi Bachya ben Asher (“Rabbeinu Bachya”) paraphrasing 11th-century Tobias ben Eliezer’s Pesikta Zutrata; translation of Bachya in www.sefaria.org.

- Shemot Rabbah, ibid.

- Abraham ben Meir ibn Ezra, translation in www.sefaria.org.

- Tur HaArokh, by Rabbi Jacob ben Asher (c. 1269 – c. 1343), translation in www.sefaria.org.

- Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch, The Hirsch Chumash: Sefer Shemos, translation by Daniel Haberman, Feldheim Publishers, Jerusalem, 2005, p. 53.

- Tur HaArokh, ibid.

- Seder Olam Rabbah 5:2, 2nd century C.E.

- Rashbam (12th-century rabbi Shmuel ben Meir) and Chizkuni (a 13th century collection of commentary).

- Da-at Zekinim, a 12th-13th century collection of commentary, upped the ante by claiming that the pharaoh and his advisors spoke 70 languages, and would ridicule Moses if he could not answer them in the same tongues.

- Exodus 1:11-14, 3:7-9.

- In Exodus 2:12, Moses glances around first, then kills the Egyptian without a witness, then buries the body in the sand.

7 thoughts on “Shemot: Not a Man of Words”