(This is the third post in a series about the interactions between Moses and God on Mount Sinai, a.k.a. Choreiv, and how their relationship evolves. If you would like to read one of my posts about this week’s Torah portion, Beshallach, you might try: Beshallach: See, Fear, Trust, Sing.)

Moses is shepherding the flock of his Midianite father-in-law when he approaches the “mountain of God”, called Choreiv or Sinai, and turns aside to examine a fire in a thornbush that does not burn the branches. God speaks out of the fire, ordering him to lead the Israelites from Egypt to the land of Canaan. But although Moses feels empathy for the oppressed Israelites, he does not want the job. Either fear or deep humility drives him to find one objection after another.

Who am I?

His first excuse for not going to Egypt, which I discussed in last week’s post, Shemot: Empathy, Fear, and Humility, is: “Who am I that I should go to Pharaoh and that I should bring out the Israelites from Egypt?” (Exodus 3:11)

And God replies: “But I will be with you.” (Exodus 3:12) Moses is not encouraged, but he does not argue with God. He moves on to his next question.

Who are you?

Then Moses said to the elohim: “Hey, I come to the Israelites and I say to them: ‘The elohim of your father sent me to you.’ And they say to me: ‘What is his name?’ What should I say to them?” (Exodus 3:13)

elohim (אֱלֺהִים) = god, gods, God. (A general term, not a name of God.)

Many commentators have offered insights about Moses’ request for God’s name, insights based on the assumption that Moses already knows all the names of God that have already been mentioned in the book of Genesis, and so do the Israelites in Egypt.1 But why should we make this assumption? Moses grew up in an Egyptian household. He did not even go out to look at the Israelite men doing forced labor until he was an adult, and he fled to Midian shortly after that. There is no reason to think he learned any names of God from the Israelites—or that the book of Genesis had been written yet.

The only name of God that Moses might know is God’s four-letter personal name, Y-H-V-H. Some modern commentators theorize that Y-H-V-H was originally the name of a Midianite god.2 If so, the author(s) of this story in Exodus could have drawn from a tradition that Moses’ father-in-law, a Midianite priest, taught him the God-name Y-H-V-H.

But even so, Moses would not expect that a Midianite god-name could help him gain the trust of the Israelites in Egypt.

Moses’ request for a name of God to tell the Israelites seems more like an extension of Moses’ first objection: he is not qualified for the job in Egypt, he is out of his depth. He knows the names of a number of Egyptian gods, but he does not know the name of the God speaking to him now from out of the fire in the bush. How can he be the prophet of a God he does not even know?

Another reason for Moses’ request for a name is that he is afraid the Israelites will not believe he is the agent of their God. What could he possibly say or do that would make them trust him?

But Moses, who has already hidden his face from God out of fear, hides his real question behind a more polite one: Suppose he goes to Egypt and the Israelites ask for God’s name. What should he say?

An unhelpful reply

And Elohim said to Moses: “Ehyeh what ehyeh.” And [God] said: “Thus you must say to the Israelites: Ehyeh sent me to you.” (Exodus 3:14)

ehyeh (אֶהְיֶה) = I will be, I will become, I have not finished being, I have not finished becoming. (The root verb hayah, הָיָה = was, became. The prefix e-, אֶ indicates both the first person singular and the imperfect form of the verb. Biblical Hebrew often uses the imperfect as a future tense, but it can also mean the action has not been completed.)

Commentators have a field day with this verse. But its theological implications do nothing for Moses’ dilemma. I can imagine him shuddering at the thought of what would happen to a stranger who showed up in Egypt and tried to explain “Ehyeh what ehyeh” to the Israelites.

Perhaps God hopes Moses will ponder “Ehyeh what ehyeh” in the future and learn something about the nature of God. But clearly he needs a different answer to his question about what name to give if the Israelites ask him to identify the God who sent him.

Then Elohim said further to Moses: “Thus you will say to the Israelites: ‘Y-H-V-H, the elohim of your fathers, the elohim of Abraham, the elohim of Isaac, and the elohim of Jacob, sent me to you.’ This is my name forever, and this is how I will be remembered from generation to generation.” (Exodus 3:15)

Y-H-V-H (י־ה־ו־ה) = the four-letter personal name of God (also called the tetragrammaton), spelled without hyphens in the Hebrew bible and Jewish prayers. For less sacred uses, Jews insert typographic marks such as hyphens, or replace the tetragrammaton with a synonym. (For possible etymologies of Y-H-V-H,see my post: Beshallakh & Shemot: Knowing the Name.)

The book of Exodus does not say whether the name Y-H-V-H was passed down among the Israelites during the 200 or more years they live in Egypt. Nor does it say whether the Israelites still tell stories about Abraham, Isaac, and/or Jacob. But even if they were familiar with the tetragrammaton and the three patriarchs, would knowing these names help Moses with his mission?

The God speaking out of the fire in the bush seems to think so, because God continues:

“Go and gather the elders of Israel, and you must say to them: “Y-H-V-H, the God of your fathers, appeared—the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob—saying: ‘I have definitely noticed you and what is being done to you in Egypt. And I said I will bring you up from the misery of Egypt to the land of the Canaanites …’ And they will listen to your voice. Then you will come, you and the elders of Israel, to the king of Egypt … and you will say to him: ‘Y-H-V-H, the God of the Hebrews, has met us. So now please let us go on a journey of three days into the wilderness, and we will make slaughter-sacrifices to Y-H-V-H, our elohim.’” (Exodus 3:16-18)

Then God predicts that the pharaoh will not let the Israelites leave until after God has stricken Egypt with “wonders”, and that when they do leave, the Egyptian people will send them off with silver, gold, and clothing.

Moses is not convinced. He is too fearful, and maybe also too humble, to believe God will make everything come out all right.

Trust in miracles

And Moses replied, and he said: “But they, ya-aminu not in me, and they will not pay attention to my voice. Indeed, they will say: ‘Y-H-V-H has not appeared to you!’” (Exodus 4:1)

ya-aminu (יַאֲמִינוּ) =they will trust, they will believe.

Perhaps Moses does not expect any sympathy from the Israelites because he remembers when he returned to the scene of his sole crime (the murder of an Egyptian man who was beating an Israelite), and saw two Israelite men fighting. He asked one Israelite why he was striking the other, and the Israelite replied:

“Who appointed you as an officer and judge over us? Are you going to kill me, as you killed the Egyptian?” (Exodus 2:14)

How can Moses protest that the Israelites will not believe him when God has just said “And they will listen to your voice”? Listening implies a willingness to believe what is said. The 16th-century commentator Sforno wrote that Moses was not referring to his first speech to the Israelites, but to later events.

“Once the people will see that Pharaoh will refuse to let them go, they will lose faith in me and will not listen to my promises … for they know that when God says something it will be so. They will not be able to account for my failure except by claiming that I am an impostor.” (Sforno)3

The God character in this story is patient, and responds with a new approach. According to 14th-century commentary by Rabbeinu Bachya: “This is why God had to equip Moses with the ability to perform certain miracles to help convince the people that he was no charlatan.”4

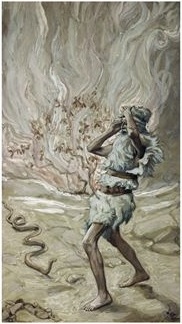

Then Y-H-V-H said to him: “What is this in your hand?” He said: “A staff.” And [God] said: “Throw it to the ground!” And he threw it to the ground, and it became a snake. And Moses fled from its face. Then Y-H-V-H said to Moses: “Reach out your hand and grasp it by its tail!” And he reached out his hand and got a firm hold on it, and it became a staff in his fist. [God said] “So that ya-aminu that Y-H-V-H, the elohim of their fathers, the elohim of Abraham, the elohim of Isaac, and the elohim of Jacob, appeared to you.” (Exodus 4:2-5)

Here God gives Moses exactly what he asked for. Demonstrating this miracle is indeed likely to make the Israelites trust him and believe that their own god sent him.

And Moses, who has been consistently fearful from God’s first words to him until he flees from the snake that used to be his own staff, now summons his courage and grabs the snake firmly. At that moment, at least, he trusts God to protect him.

Why does God pick this particular miracle? 12th-century commentator Abraham ibn Ezra wrote that God started with Moses’ staff for practical reasons. “God gave Moses a sign via an object that was always with him, the staff, Moses’ walking stick, as is the custom with elders. Moses would not appear as a shepherd before Pharaoh.”5

Why does God make the staff turn into a snake? 19th-century rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch wrote that the transformation of staff to snake and snake to staff will demonstrate to the Israelites that God has the power to overturn both human authority and hostile forces (two different descriptions of the pharaoh).

“You have been sent by the one sole God Who, if He so desires, can cause the very thing on which man relies for support, and which serves him as an instrument of his authority, to turn against him. Conversely, if He so desires, God can take a hostile force that is feared and shunned by man and place it into his hand as an accommodating support and tractable tool.” (Hirsch)6

Another line of commentary claimed that both the staff-snake miracle and the following miracle demonstrate that God is in charge of life and death.

And Y-H-V-H said further to him: “Please place your hand in your bosom!” And he placed his hand in his bosom [the front fold of his robe], and he took it out, and hey! His hand had tzara-at like snow! Then [God] said: “Return your hand to your bosom!” And he returned his hand to his bosom. Then he took it out of his bosom, and hey! It was restored as his flesh. (Exodus 4:6-7)

tzara-at (צָרַעַת) = a skin disease characterized by dead-white patches of skin.

16th-century rabbi Ovadiah Sforno, following 14th-century Rabbeinu Bachya, explained both miracles this way: “Here is a staff which is an inert object, and the hand which is something very much alive. I will demonstrate that I can kill that which is alive and bring to life that which is dead. I will make your hand useless and your staff will suddenly come alive.”7

Commentators have also pointed out that the second miracle points at Moses’ inappropriate speech even more than the first, since the Talmud considered tzara-at a divine punishment for evil speech.8

And Hirsch added: “For it demonstrates that not only the staff, but also the hand that holds and guides the staff, is subject to God’s control. … even if man seeks to withdraw into himself and rely only on himself, he cannot be sure of himself. If God wishes, He can plant discord even within man’s inner self.”9

After providing Moses with these two miracles for demonstration purposes, God says that if the Israelites do not believe him after the first sign, they will believe him after the second. But if even that does not work,

… and they do not listen to your voice, then you must take some water of the Nile, and you must pour it out on the dry land, and the water that you take from the Nile will become blood on the dry land. (Exodus 4:9)

Moses does not ask for a fourth miracle to demonstrate his bona fides. Instead he moves on to another excuse to stay home in Midian, another reason why he is not the right person for God’s mission.

To be continued …

- For example, Ramban (Nachmanides), Or HaChayim, and Samson Raphael Hirsch wrote that Moses was really asking which attribute of God would rescue the Israelites from Egypt, because that would be important information for the Israelites.

- E.g. Israel Knohl, https://www.thetorah.com/article/yhwh-the-original-arabic-meaning-of-the-name.

- Rabbi Ovadiah Sforno, translated in www.sefaria.org.

- Rabbeinu Bachya (Rabbi Bachya ben Asher), translated in www.sefaria.org.

- Abraham ben Meir ibn Ezra, translated in www.sefaria.org.

- Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch, The Hirsch Chumash: Sefer Shemos, translation by Daniel Haberman, Feldheim Publishers, Jerusalem, 2005, p. 50.

- Sforno, ibid.

- E.g. Rashi and 14th-century rabbi Jacob ben Asher in Tur HaArokh.

- Hirsch, p. 51.

4 thoughts on “Shemot: Names and Miracles”