Jacob was born hanging onto the heel of his twin brother, Esau.

After that his brother emerged, and his hand was grasping the akeiv of his brother; so they called his name Ya-akov. (Genesis 23:26)

akeiv (עָקֵב) = heel.

Ya-akov (יַעֲקֺב) = “Jacob” in English. (From ya-ekov, יַעְקֺב = he grasps by the heel; he cheats.)

The book of Genesis implies that from the beginning, Ya-akov wanted to be the firstborn son. In the Torah portion Toledot he tried to replace his brother twice, first by trading a bowl of stew for Esau’s inheritance as the firstborn, and then by impersonating Esau to steal their blind father Isaac’s blessing.

And Isaac loved Esau, because [Esau brought] hunted-game for his mouth. But Rebecca loved Ya-akov. (Genesis 25:28)

Their mother, Rebecca, arranged Jacob’s impersonation. Then when Esau vowed to kill his brother for cheating him twice, she arranged for Ya-akov to flee to her brother’s house in Padan-Aram. Twenty years later, Jacob returned with a large family of his own. On the eve of his reunion with Esau in last week’s Torah portion, Vayishlach (Genesis 32:4-36:43), Ya-akov receives a second name.

Vayishlach: A new name

And Ya-akov was left alone. And a man wrestled with him until dawn rose. (Genesis 32:25)

The Hebrew Bible often calls a divine messenger (or angel) a “man” at first. Other theories are that Jacob’s wrestling partner is a demon, or his own alter ego or subconscious.1 They wrestle all night, and neither prevails. Then the mysterious “man” dislocates Jacob’s hip and said:

“Let me go, because dawn has risen!” But Ya-akov said: “I will not let you go unless you bless me.” Then [the “man”] said to him: “What is your name?” And he said: “Ya-akov.” (Genesis 32:27-28)

Twenty years before, when Jacob impersonated Esau to steal their father’s blessing, Isaac had asked him to identify himself. At that time, Jacob had answered: “I am Esau.” (Genesis 27:19) But when Jacob asks the unnamed wrestler to bless him, he answers: “Ya-akov.” (Genesis 32:28)

And [the “man”] said: “It will no longer be said that Ya-akov is your name, but instead Yisrael, because sarita with God and with men and you have prevailed.” (Genesis 32:29)

Yisrael (יִשְׂרָאֵל) = “Israel” in English. (Possibly yisar, יִשַׂר = he strives, contends, perseveres + Eil, אֵל = God, a god. This combination could mean either “God strives” or “He strives with God”.)

sarita (שָׂרִיתָ) = you strove, you persevered.

A much shorter, dryer story about Jacob’s new name appears later in the portion Vayishlach:

And God appeared to Ya-akov again when he came from Padan-Aram, and [God] blessed him. And God said to him: “Your name is Ya-akov. Your name will not be called Ya-akov again, because your name will be Yisrael.” (Genesis 35:9-10)

Modern scholars attribute the two versions of the naming story to two different sources; the story about wrestling probably comes from a non-P author, while the less colorful renaming by God comes from a P author.2 Both versions give Ya-akov the additional name Yisrael, so this is not a case of two traditions using two different names.

In subsequent biblical books, Yisrael is also the name of a people, Jacob’s descendants. And in biblical poetry, some couplets call the people both Ya-akov and Yisrael, treating the two names as mere synonyms.3

In the rest of the book of Genesis, Jacob son of Isaac is referred to as Ya-akov most often, but occasionally the text calls him Yisrael. Does the switch to Jacob’s new name mean anything?

Vayishlach: Equanimity?

The first time the narrative uses the name Yisrael is right after the household stops on the road so Jacob’s favorite wife, Rachel, can give birth. She dies right after Jacob’s twelfth and final son, Benjamin, is born.

Ya-akov set up a standing-stone over her grave … And Yisrael moved on and pitched his tent beyond the tower of Eider. (Genesis 35:20-21)

Ya-akov grieves over the death of his favorite wife. But Yisrael moves on; he is responsible for getting his flocks to good pastureland.

And it happened when Yisrael was residing in that land: Reuben went and lay with Bilhah, his father’s concubine. And Yisrael paid attention. (Genesis 35:22)

Yisrael pays attention, but he does not act. He does not even bring up the episode until he is on his deathbed. The old Ya-akov might have been overcome with outrage that his eldest son usurped him, taking possession of a woman who belongs to him. But the new Yisrael is either too tired to react, or willing to accept whatever happens.

Vayeishev: Playing favorites

This week’s Torah portion, Vayeishev (Genesis 37:1-40:23), begins with Jacob under his old name.

And Ya-akov settled in the land of his father’s sojournings, the land of Canaan. And these are the histories of Ya-akov: Joseph, seventeen years old, shepherded a flock along with his brothers, and he was a youth with the sons of Bilhah and the sons of Zilpah, wives4 of his father. And Joseph brought bad gossip to their father. (Genesis 37:1-2)

Joseph is Rachel’s first son, so Jacob loves him more than the sons of his other three wives.

And Yisrael loved Joseph more than all his sons, since he was a son of old age to him. And he made him a fancy tunic. And his brothers saw that it was he whom their father loved more than his brothers, so they hated him, and they could not speak to him in peace. (Genesis 37:3-4)

Transparent favoritism is not surprising from someone who grew up with parents who favored one son over the other. But why did the author or redactor attribute this favoritism to Yisrael rather than to Ya-akov? After all the striving that Jacob did while wrestling with God’s messenger (and/or himself), we might expect Yisrael to choose peace in the family, and treat his sons more fairly, perhaps giving each one a different gift.5

Shortly after that, all ten of Joseph’s older brothers take the family flocks to Shekhem, a journey of about 60 miles (about 100 kilometers) from their home in Hebron.

And Yisrael said to Joseph: “Aren’t your brothers shepherding in Shekhem? Go, and I will send you to them!” (Genesis 37:13)

Rashbam wrote: “The wording reflects Ya-akov’s surprise that Joseph’s brothers chose to tend their sheep in a dangerous location such as Shekhem, where they had killed the local inhabitants not so long ago.”6

At least Joseph’s brothers are ten strong young men traveling together. But why does Yisrael risk sending the teenage Joseph to Shekhem alone? What if someone who remembered the massacre identifies him as a member of the notorious family of killers?

Maybe Jacob is in denial, having forgotten the atrocities his older sons committed in Shekhem. In that case, the name Yisrael here might indicate Jacob’s old age and his desire for peace, but not increased wisdom.

And [Joseph] said to him: “Here I am.” And [Jacob] said to him: “Please go and look into the well-being of your brothers and the well-being of the flocks, and bring back word to me.” (Genesis 37: 14)

Jacob deliberately sends out his favorite son to report on his brothers. Yet he does not seem to worry about the safety of the seventeen-year-old boy when he is far from home, surrounded by brothers who hate him (and may well assume he intends to bring back to their father more “bad gossip” about them).

Classic commentators7 maintained that Jacob assumed his older sons would never attack Joseph. Yet Jacob himself once had to flee to another country because his own brother had vowed to kill him. Perhaps in old age, Jacob was losing his ability to connect the past with the present.

On the other hand, Yisrael might realize that he has pampered Joseph too long. He might even realize that giving only Joseph an expensive gift had contributed to his favorite son’s feeling of entitlement, which then led to Joseph telling his jealous brothers his two dreams in which they bowed down to him.8 Perhaps Yisrael, the man who wrestled with himself, sees Joseph’s psychological problem and takes the risk of sending him to Shekhem so he can learn self-reliance and grow up. He might even comfort himself with the thought that surely God would look after Joseph, and he would come home as a wiser young man.

Vayeishev: Mourning

Joseph finds no one in the vicinity of Shekhem except a man who tells him his brothers traveled on to Dotan. When he arrives in Dotan, his brothers seize him, throw him in an empty cistern, threaten to kill him, and finally sell him as a slave to a caravan bound for Egypt. Then they come up with a plan for fooling their father.

And they took Joseph’s tunic, and they slaughtered a hairy goat and dipped the tunic in the blood … and they brought it to their father and said: “We found this. Please recognize whether it is your son’s tunic or not.” (Genesis 37:31-32)

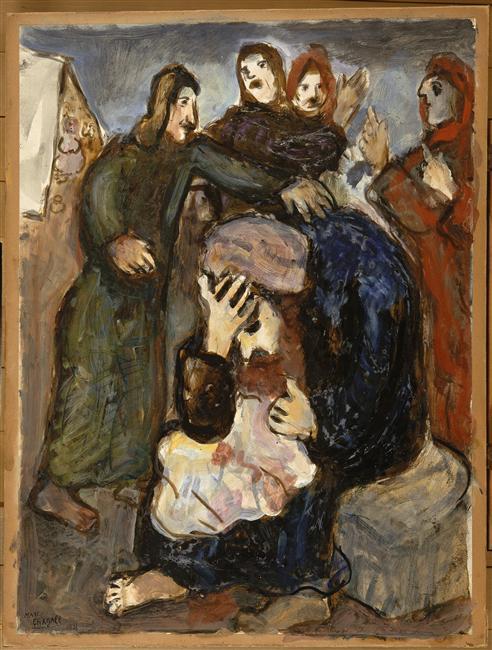

Jacob falls for the deception; he assumes Joseph was eaten by a wild beast. He grieves as Ya-akov.

And Ya-akov tore his clothes, and he put sackcloth around his hips, and he mourned over his son a long time. And all his sons and all his daughters rose to comfort him, but he refused to be comforted. And he said: “If [only] I would go down to my son mourning, to Sheol!” And his father wept for him. (Genesis 37:34-35)

Jacob is entitled to grieve a long time over the death of his favorite son. But Ya-akov’s reaction is almost selfishly extravagant, consistent with his self-absorption while he was growing up: he rejects his children and grandchildren, and declares that he wants to die. His alter ego, Yisrael, does not have a chance to emerge.

The Torah does not refer to Jacob as Yisrael again until next week’s Torah portion, Mikeitz. Stay tuned for my next post, Mikeitz: Yisrael versus Ya-akov, Part 2.

- See my post Toledot & Vayishlach: Wrestlers.

- The documentary hypothesis discerns four traditions braided into the Pentateuch, named J, E, P, and D by Julius Wellhausen in the 19th century. In the 21st century the scholarly consensus is that there were more than four writers, and the story lines previously identified as J and E should all be called “non-P”. “P” is the “priestly” tradition, which was more interested in priestcraft than in narrative.

- Robert Alter, The Five Books of Moses, W.W. Norton & Co., New York, 2004, p. 181.

- Genesis always calls Leah and Rachel Jacob’s wives. Bilhah and Zilpah are their slaves, but after they become Jacob’s concubines, they are sometimes called his wives.

- This is what Jacob’s grandfather Abraham did in Genesis 25:5-6.

- Rashbam (12th-century Rabbi Shmuel ben Meier) translated in www.sefaria.org. In Genesis 34:1-31, Jacob’s older sons tricked all the men of the town of Shekhem into circumcising themselves, then slaughtered them and took their women and children as booty.

- Including Radak (Rabbi David Kimchi, ca. 1200), Chizkuni (editor Chizkiah ben Manoach, 13th century), and Or HaChayim (Rabbi Chayim ibn Attar, 18th century).

- See my post: Vayeishev: Favoritism.

One thought on “Vayishlach & Vayeishev: Yisrael Versus Ya-akov, Part 1”