This week’s haftarah is the entire book of Obadiah, which is one chapter long! Obadiah protests that when the Babylonian army destroyed Jerusalem and its temple in 587-586 B.C.E., the small kingdom of Edom took advantage of the chaos to prey on their Israelite neighbors.

Didn’t you come into the gate of my people

on its day of calamity?

Didn’t you, too, look at its misery

on its day of calamity?

And didn’t you reach out for its wealth

on its day of calamity? (Obadiah 1:13)

And didn’t you stand at the crossroads

to cut down its fugitives?

And didn’t you deliver up its survivors

on the day of distress? (Obadiah 1:14)

When the Day of God draws near

against all the nations

As you did, it will be done to you.

Your dealings will come back on your head! (Obadiah 1: 15)

The rest of the book predicts that God will take revenge by utterly destroying the Edomites. I have not written about this haftarah before because revenge fantasies turn me off. But there is more than one way to interpret the Hebrew Bible.

How to interpret the bible

Back in the 1st century C.E., before the Romans destroyed the second temple in Jerusalem, Philo of Alexandria interpreted some passages in Genesis as allegories of Stoic philosophical concepts, identifying the characters with universal human aspects. (For example, Adam is the mind, Eve is the senses, and Noah is the state of tranquility.)

An allegorical tale in the 5th-century Babylonian Talmud tractate Chagigah features four actual Jewish scholars from the first century C.E., each with a different approach to biblical interpretation.1 They all enter pardeis (פַּרְדֵּס, the Persian word for “orchard”, a metaphor for deep Torah study which eventually became the English word “paradise”), but only one of them comes out whole. Rabbi Elisha ben Avuya, a.k.a. Acheir (אַחֵר, “Other”), was a literalist who found contradictions in the bible; Chagigah says he became a heretic. Tanna Shimon Ben Zoma found metaphorical meanings, and tried to reconcile different texts that employed the same uncommon Hebrew words; Chagigah says he lost his mind. Tanna Shimon Ben Azzai was a mystic; Chagigah says he died beholding God’s presence. Only Rabbi Akiva, who used reason to determine which biblical phrases should be taken literally and which metaphorically, left pardeis in the same condition as when he entered.

In the 13th century, the Spanish kabbalist Moshe de León pioneered the use of the word pardeis as an acronym for four types of exegesis, which Jews still use:

Peshat (פְּשַׁט, “stripped down”) is the plain, literal meaning of a text.

Remez (רֶמֶשׂ, “swarming creatures”) expands the literal meaning to cover similar situations, and transforms texts into allegories.

Derash (דְּררַשׁ, “inquiry”) adds to a text by drawing moral lessons from it, and/or inventing additional details to enhance a story’s meaning.

Sod (סוֹד, “secret”) uses words to point at an esoteric mystery that cannot be expressed in words.

Applying PaRDeiS to the haftarah

Before indicating what crimes the Edomites committed against the Israelites in Jerusalem, Obadiah quotes God as telling Edom:

The arrogance of your heart deceived you,

Dwellers in the clefts of the cliffs.

High in your dwellings, saying in your heart:

“Who could pull me down to earth?” (Obadiah 1:3)

If you were lofty as an eagle,

Or if you put your nest between the stars,

From there I will pull you down,

Declares God. (Obadiah 1:4)

A peshat reading of these two verses would point out that the ancient kingdom of Edom (located in the south of what we now call Jordan) was mountainous and rocky, poor for agriculture but easy to hide in and difficult to invade. The plain meaning is that the Edomites mistakenly believe they are invulnerable—even from God.

A Talmudic remez reading is that “the stars” means “the just”.2 Edomites believe they are among the just, but the book of Genesis says they are descended from Esau, Jacob’s undesirable brother. Midrash Tanchuma cited God’s promise to Abraham that his descendants would be like the stars in the heavens, and concluded that Obadiah’s reference to stars “can only mean Israel”.3

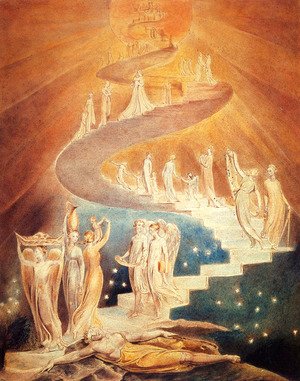

Vayikra Rabbah combined Obadiah 1:4 with Jacob’s dream in Genesis 28:12, then added to the story with the following derash:

“It teaches that the Holy One, blessed be He, showed Jacob the guardian angel of Babylon ascending and descending, of Media ascending and descending, of Greece ascending and descending, and of Edom ascending and descending. The Holy One blessed be He said to Jacob: ‘You, too, will ascend.’ At that moment, Jacob our patriarch grew fearful and said: ‘Perhaps, God forbid, just as there was descent for these, so it will be for me.’ The Holy One, blessed be He, said to him: ‘You, have no fear; if you ascend, there will be no descent for you forever.’ He did not believe, and he did not ascend. … The Holy One blessed be He said to him: ‘Had you believed and ascended, you would never have descended. Now that you did not believe and did not ascend, your descendants will be subjugated by the four kingdoms in this world with land taxes, produce taxes, animal taxes, and head taxes.’”4

My own derash interpretations tend toward drawing moral lessons.5 What strikes me about Obadiah’s two verses on Edom’s arrogance is the idea that arrogant people believe they occupy high positions because they are superior. But their high positions are both barren (rocky) and precarious (cliffs).

The arrogant are afraid of being pulled down to earth. They spend so much time and energy defending their status and egos that they accomplish less than humble, hard-working people—from down-to-earth farmers to the rabbis and other religious leaders who care more about their work than about self-glorification.

But when the arrogant are successful, they question whether anything could pull them down. Obadiah points out that they are wrong. These exalted narcissists are not eagles, but human beings. Even autocrats and superstars are vulnerable, because they live in the complex world of human interactions. Millions of people may look up to them now, but anyone can fall off the cliff. Anyone can be pulled down.

It is better to do good work on the ground than to “put your nest between the stars”.

That is my derash. I am not a mystic, although I know a little about kabbalah, so a sod reading is beyond me; it might as well be between the stars.

- Talmud Bavli, Chagigah 14b.

- Talmud Yerushalmi, Nedarim 3:8:2.

- Midrash Tanchuma, 500-800 C.E., translated in www.sefaria.org, citing Genesis 15:5.

- Vayikra Rabbah 29:2:, circa 500 C.E., translated in www.sefaria.org.

- I reserve fleshing out biblical stories with additional narrative for my Torah monologues.