Abraham and God debate the fate of Sodom in this week’s Torah portion, Vayeira (Genesis 18:1-22:24).

The portion is called Vayeira, (וַיֵרָא) “And he appeared”, because in the first sentence God appears to Abraham—as three men.

Abraham provides lavish hospitality, as he would for any humans trekking across the sparsely populated hills to his campsite at Mamre (near present-day Hebron). Then one of the “men” tells Abraham his wife Sarah (who is 89 years old) will have a son. And without transition, the text reports God speaking first to Abraham, then to Sarah.1 Often in the Hebrew Bible a man turns out to be a divine messenger or angel, and the transition between the messenger speaking and God speaking is seamless.

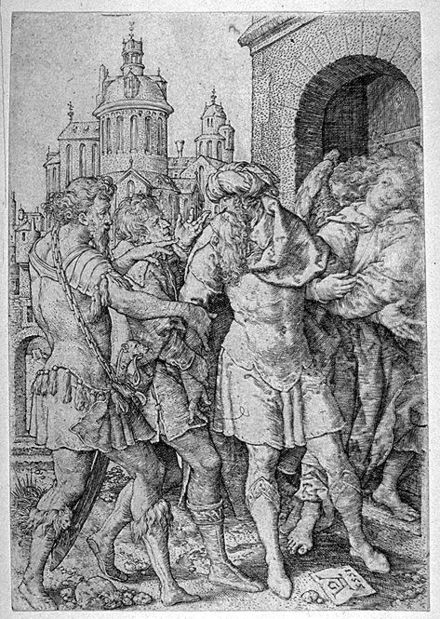

Then the men got up from there, and they looked down at Sodom. And Abraham was walking with them to send them off. (Genesis 18:16)

The “men” and Abraham walk to a hilltop from which they could look down at the Dead Sea and the towns of Sodom and Gomorrah near its shore.

Next comes a Shakespearean aside, in which God’s thoughts are expressed in words.

And God said: Will I hide from Abraham what I am doing? (Genesis 18:17)

Whenever the Hebrew Bible reports a character’s silent thoughts, the text uses the verb “said” (amar, אָמָר), but the context makes it clear that the character is saying something silently to himself or herself. Here, God continues thinking:

For Abraham will certainly become a nation great and numerous, and all the nations of the earth will be blessed through him. (Genesis 18:18)

The God character is recalling the promise at the beginning of last week’s Torah portion, Lekh Lekha. There, God told Abraham to leave his home and go “to the land that I will show you”, which turned out to be Canaan.

“And I will make you a great nation, and I will bless you, and I will make your name great. … And all the clans of the earth will seek to be blessed through you.” (Genesis 12:2-3)

Abraham did indeed leave home and go to Canaan. But the future that God promised can only happen if Abraham teaches his people the right behavior. God thinks:

ForI have become acquainted with him so that he will give orders to his sons and his household after him; then they will keep the way of God to do tzedakah umishpat, so that God will bring upon Abraham what [God] spoke concerning him. (Genesis 18:19)

tzedakah (צְדָקָה) = righteousness, acts of justice. (From the root tzedek, צֶדֶק = right, just.)

umishpat (וּמִשְׁפָּט) = and mishpat (מִשְׁפָּט) = legal decision, legal claim, law.

One way to translate tzedakah umishpatis: “what is right and lawful”. The way Abraham will become a great nation that is a source of blessing, God thinks, is by teaching the way of God—what is right and lawful—to his household, so they will pass on the information to the generations after him.

Why God is teaching Abraham

Naturally God wants Abraham to convey the correct information about the way of God. Now God is wondering whether it would be helpful to tell Abraham what is about happen in Sodom.

We know God switches from thinking to speaking out loud—or at least speaking so that Abraham can hear—because he responds to what God says next.

Then God said: “The outcry of Sodom and Gomorrah is great, because their abundant guilt is very heavy! Indeed I will go down, and I will see: Are they doing like the outcry coming to me? [If so,] Annihilation! And if not, I will know.” The men turned their faces away from there and they went to Sodom, while Abraham was still standing before God. (Genesis 18:20-22)

The God character in the Torah sees and hears a lot from the heavens above, but not everything, so sometimes God or a divine messenger comes down to the earth for more information.2 Abraham now knows that if Sodom is as guilty as God has heard, God will annihilate it. Why does God give him that information ahead of time? Perhaps God is testing Abraham, prompting him to think through what is right and lawful in a particular situation. If Abraham asks God a question about the divine plan for Sodom, they can discuss it—a subtle form of teaching.

Is Abraham teaching God?

Then Abraham came forward and said: “Would you sweep away the tzadik along with the wicked one?” (Genesis 18:23)

tzadik (צַדִּיק) = righteous, innocent. (Also from the root tzedek. The Hebrew Bible applies this adjective to men, nations, and God.)

Abraham probably knows already what God is about to find out: that rape and murder are rampant in Sodom. After all, his own nephew, Lot, lives in that city. And Lot knows that travelers are not safe in the town square after dark. Later in the Torah portion, after Lot has brought the two divine messengers who look just like men into his own house to spend the night, the other men in Sodom come to his door and order him to bring the strangers out to be raped. And Lot knows they will not take no for an answer.4

But so far, Lot has done nothing immoral himself, though he has tolerated the immorality around him. And as far as Abraham knows, there might be other innocent men in Sodom.

Abraham asks God:

“What if there are fifty tzadikim inside the city? Would you sweep away, and not pardon the place, for the sake of the fifty tzadikim who are in it? Far be it from you to do this thing, to bring death to the tzadik along with the wicked! Then the tzadik would be like the wicked. Far be it from you! The judge of all the earth should do justice!” (Genesis 18:24-25)

tzadikim (צַדִּיקִם) = plural of tzadik.

According to the commentary Or HaChayim, when Abraham said then the tzadik would be like the wicked, he meant that “if God applied the same yardstick to all creatures alike, the righteous would be deprived of every incentive to be righteous.”5 So the tzadikim in Sodom would give up and join their neighbors in doing evil.

However, not every man thinks raping and murdering other men would be fun if he could get away with it. So I think Abraham means that if God annihilates the whole city, God would be treating the tzadik just like the wicked man—which would be unjust.

And God said: “If I find in Sodom fifty tzadikim in the midst of the city, then I will pardon the whole place5 for their sake.” (Genesis 18:26)

Why does the God character agree immediately with Abraham’s request?

One answer is that God intended from the beginning to spare Sodom if there were enough tzadikim in the city; that is why God sent the two messengers down to find out how bad things really were. Abraham is merely suggesting a number.

Abraham answered, and said: “Hey, please, I am willing to speak to my lord, and I am dust and ashes. Perhaps the fifty tzadikim lack five. Will you ruin the whole city on account of the five?” And [God] said: “I will not ruin if I find forty-five there.” (Genesis 18:27-28)

Abraham’s reference to himself as dust and ashes is probably an expression of humility, intended to salve God’s pride. After all, Abraham is attempting to teach a being who could kill him in an instant.

Abraham asks if God would annihilate the whole city if there are forty tzadikim, then thirty, then twenty. Each time God promises to refrain from destroying Sodom for the sake of that number of tzadikim. Then Abraham says:

“Please don’t be angry, my lord, and I will speak just once more. Perhaps ten will be found there.” And [God] said: “I will not ruin, for the sake of the ten.” And God left, as [God] had finished speaking to Abraham. And Abraham returned to his [own] place. (Genesis 18:33)

Why does Abraham stop with ten? Perhaps he just assumes that there must be more than ten tzadikim in Sodom.

But according to S.R. Hirsch, God agreed to save Sodom not in order to keep the ten innocent men alive, but because a society that tolerated a certain number of righteous people was not totally evil, and so might someday reform. The number matters; “Only in the case of a medium number—where the righteous are too many to be inconsequential and too few to be intimidating—does the fact that the righteous are allowed to exist and are tolerated have full significance.”6

This explanation makes the God character more optimistic and forgiving than in the many Torah passages where God sends plagues to punish the Israelites for infractions in which not everyone participated, and arranges mass slaughters of non-combatants in war. Perhaps the God character does not fully absorb Abraham’s lesson.

What do God and Abraham teach?

The God character, by agreeing with each of Abraham’s proposals, teaches him that questioning God is acceptable and worthwhile.

According to Jonathan Sacks,7 “Abraham had to have the courage to challenge God if his descendants were to challenge human rulers, as Moses and the Prophets did. … This is a critical turning point in human history: the birth of the world’s first religion of protest—the emergence of a faith that challenges the world instead of accepting it. … meaning: be a leader. Walk ahead. Take personal responsibility. Take moral responsibility. Take collective responsibility.”

But Abraham also teaches God something, when he says: Far be it from you to do this thing, to bring death to the tzadik along with the wicked! … The judge of all the earth should do justice!”

According to Jerome Segal,8 “In arguing that justice requires that the innocent be treated differently from the guilty, Abraham is not only asserting a moral principle but also asserting that it is binding upon God. Thus, the independence of the moral order is again affirmed. Morality does not depend on God for its reality. It stands apart as something to which God must conform.”

Thus God teaches Abraham what is right and just, and Abraham teaches God what is just and right. It takes both of them to advance the cause of morality.

Now it is our turn to consult our inner voices of conscience and reason and advance the cause further.

- Genesis 18:9-15. See my post: Vayeira: On Speaking Terms.

- The first example in Genesis of God coming down to the earth for more information is in the story about the Tower of Babel: And God went down to look at the city and the tower that the humans had built. (Genesis 11:5)

- Genesis 13:5-13.

- Genesis 19:1-8.

- Chayim ibn Attar, Or HaChayim, 18th century, translated in www.sefaria.org.

- Rashi (11th-century rabbi Shlomoh Yitzchaki) wrote that the whole place means Sodom and its satellite towns, such as Gomorrah.

- Samson Raphael Hirsch, The Hirsch Chumash: Sefer Bereshis, translated by Daniel Haberman, Feldheim Publishers, Jerusalem, 2002, p. 428 and 429.

- Jonathan Sacks, Covenant & Conversation, “Answering the Call: Vayera 5781”.

- Jerome M. Segal, Joseph’s Bones, Riverhead Books, Penguin Group, New York, 2007, p. 63.

One thought on “Vayeira: Who Is the Teacher?”