A woman is ritually impure (tamei)1 after giving birth, and must stay away from anything holy for 40 days (for a boy) or 90 days (for a girl). Anyone with a certain skin condition is ritually impure, and must live outside the camp or town. If mold appears in cloth or leather and cannot be washed out, it is ritually impure, and must be burned.

This week’s Torah portion, Tazria (Leviticus 12:1-13:59) devotes 67 verses to these three situations—and next week’s portion continues the instructions. But do rules about ritual purity from about 2,500 years ago have any relevance in today’s world?

The biblical laws about keeping kosher, which appear in last week’s Torah portion, Shemini, are still observed by many Jews. And a few other ritual purity laws are followed by observant orthodox Jews—for example, the rule that a married woman must submerse in the water of a mikveh after her menstrual period ends. Other purity laws have been impossible to observe since the fall of the second temple in Jerusalem in 70 C.E., when the descendants of priests were left with a few special honors, but no longer conducted sacrificial services or ritual purifications.

Nevertheless, the Torah’s instructions about how priests should diagnose ritually impure conditions and conduct purification rituals can still be interpreted in ways that might speak to us today.

In my post Tazria: Time to Learn, Part 1, I talk about the value of a delay in returning to social life after childbirth. In Tazria & 2 Kings: A Sign of Arrogance, I discuss the connection between skin disease and excessive pride.

And what about the third topic in the portion Tazria, moldy cloth and leather? This passage can also have an alternate meaning, depending on how we translate the Biblical Hebrew words in it that refer to both physical objects and psychological meatphors.

Infected garments—or depressed traitors

The instructions begin with this verse:

If the beged has a mark of tzara-at in it—in a beged of wool or in a beged of linen— (Leviticus 13:47)

beged (בֶּגֶד) = cloth garment—or betrayal. (Identical spelling. The noun beged meaning betrayal comes from the root verb bagad, בָּגַד = deceive, betray, break faith.)

tzara-at (צָרָעַת) = a skin condition characterized by white patches lower than the surrounding skin; patches of mold in cloth, leather, or walls. (A related word, tzira-ah, צִרְעָה = depression, discouragement. Its construct form would be tzira-at, צִרְעָת = depression of, discouragement of. The noun tzira-ah is closely related to tzara-at; a depression in one’s skin becomes a depression in one’s mood.)

What is the best translation of verse 13:47, given the alternative meanings of the words beged and tzara-at?

Most translators pick the meaning that makes sense if you read the passage as a straightforward description of an event, or as a set of instructions for carrying out laws or rituals. I usually do that myself. But sometimes the English word that expresses the most straightforward meaning does not give us any idea of the alternative, metaphorical meaning of the Hebrew word. Then something is lost in translation.

A straightforward translation of Leviticus 13:47 is:

If the garment has a mark of mold in it—in a garment of wool or in a garment of linen—

An alternative translation of Leviticus 13:47 is:

If the betrayal has the mark of depression in it—in a betrayal of wool or in a betrayal of linen—

Someone who betrays another person, God, or an ideal often feels depressed. But what is a betrayal of wool or linen?

In the Torah, wool is the fabric associated with the Israelites, who own flocks of sheep. Linen is an Egyptian import.2 So with a small stretch, the translation of Leviticus 13:47 could become:

If the betrayal has the mark of depression in it—in a betrayal of Israelite ways or in a betrayal of Egyptian ways—

Weaving and leather—or drinking, mixing, and skin

If the next verse did not continue this line of thought, I would ditch the metaphorical translation and restrict myself the plain, straightforward one. But I have nothing interesting to say about the technical details of diagnosing mold in cloth. Fortunately, the next verse is:

—or in the shti or in the eirev of the linen or of the wool; or in or, or in any melekhet of or— (Leviticus 13:48)

shti (שְׁתִי) = warp (in weaving)—or drinking. (Identical spelling.)

eirev (עֵרֶב) = woof (in weaving)—or mixing.3 (Identical spelling.)

or (עוֹר) = leather, skin (including the skin of a living human being).

melekhet (מְלֶאכֶת) = craft, business, mission.

A straightforward translation of Leviticus 13:48 is:

—or in the warp or in the woof of the linen or of the wool; or in leather or in anything crafted of leather—

Here is an alternative translation of Leviticus 13:48 with the same interpretations of linen and wool I used for verse 13:47:

—or in drinking, or in the mixing of Egyptian and Israelite ways; or in skin or in any business of skin—

The Torah forbids mixing linen and wool,4 and biblical prophets warn Israelites against making alliances with Egypt or moving to Egypt.5 An example of mixing Egyptian and Israelite ways could be sex with a sibling, which was a permissible kind of marriage in Egypt, but an abomination in Israel.

The Hebrew Bible talks about three kinds of betrayal: telling lies (especially in court), breaking a vow, and deliberately violating God’s orders. What it does not mention is that if you betray a human being or God, you usually betray yourself as well, by failing to live up to your own standards. One result is likely to be depression. Traitors who feel depressed about their betrayals might indeed start drinking too much. And they might violate their own culture’s mores about sex or other aspects of life because they despair of being upright citizens.

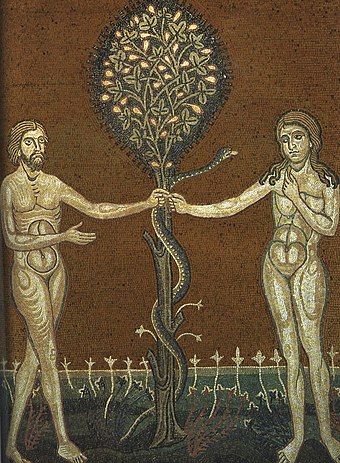

But what about a “business of skin”? The first time the word or (עוֹר) appears in the Torah is when God clothes Adam and Eve in the skins of animals before sending them out of the garden of Eden.

And God, God made for Adam and for his woman fancy garments6 of skin, and [God] clothed them. (Genesis 3:21)

Most commentators conclude that God does not make leather garments for them, but rather gives them bodies covered with skin, like all mammals. Subsequent references to or as skin merely mention skin as opposed to muscle or bone—one more physical body part. Biblical writers and commentators assume it is our physical bodies that give us the most in common with other animals. So “business of skin” could mean “animal concerns” such as food and sex.

Putting verses 13:47 and 13:48 together could yield this slightly imaginative alternative translation:

If betrayal has the mark of depression in it—in betrayal of Israelite ways or in betrayal of Egyptian ways—or in drinking, or in the mixing of Egyptian and Israelite ways; or in animality, or in any animal concerns— (Leviticus 13:47-48)

Expert help

If you notice yourself, or someone you know, behaving like this, what should you do?

The next verse in the portion Tazria gives the first instruction: the mark of tzara-at must be shown to a priest.

And the priest will look at the mark, and isolate the mark seven days. (Leviticus 13:50)

It is easy enough to isolate a cloth garment, or something made of leather. It is harder to isolate a person, but this week’s Torah portion has already described how a priest isolates people who have the skin condition called tzara-at by requiring them to live outside the camp or town. They are considered unfit for society.

On the seventh day, the priest looks at the mark again. According to the plain, straightforward translation:

If the mark has spread in the garment, or in the warp or woof of the cloth, or in the leather or in anything that is made of leather, the mark is a harmful mold; it is ritually impure. (Leviticus 13:51)

According to a metaphorical translation:

If the mark has spread, the betrayal or the drinking or the mixing or the animal behavior, it is a hurtful depression; therefore it is “ritually impure”: a condition that requires strong action.

The action the priest must carry out is to burn up the article that has tzara-at in a fire. Moldy cloth or leather can certainly be burned. But how can one burn depression due to betrayal, and all the hurtful behavior it can cause?

If a modern expert in the role of the ancient priest, perhaps a psychologist, decides the betrayer’s depression is seriously hurtful, the expert might prescribe anti-depressants—but that is not enough to stop the damage. The depressed person also needs to “burn up” their old ways. With ongoing guidance, a traitor could make recompense to the one betrayed, a drinker could quit, a person operating only by animal instinct could become dedicated to rules of reasonable behavior.

The author of this part of the book of Leviticus was probably a Levite who simply wanted a written record of how priests and the general public should interact in specific undesirable situations, such as mold in cloth and leather.

Yet two major 12th-century commentators who usually approached Torah from very different perspectives, Rambam (Rabbi Moses Maimonides) and Ramban (Rabbi Moses Nachmanides) agreed that tzara-at was actually a supernatural warning from God that a person was doing something evil. The problem had to be addressed with repentance and reform.

I suspect these traditional commentators were influenced by the alternative meanings of the words in this passage in Tzaria. Without the dual meanings, the psychology underneath the arcane ritual might get lost in translation.

- Tamei (טָמֵא) = “ritually impure”, i.e. requiring correction through a purification ritual before the person, animal, or object can return to normal life or use.

- Other fabrics available in the Ancient Near East circa 500 B.C.E. include those woven of camel hair or goat hair. Silk from China and cotton from India were not introduced until around 100 B.C.E.

- The noun eirev, which often means “mixed race”, comes from the root verb arav, עָרַב = mix, mingle.

- Leviticus 19:19 (banning any mixture of thread sources), Deuteronomy 22:11 (specifically banning cloth that combines wool and linen).

- For example, Jeremiah 42:7-22 tells the Judahites to stay in their land even under Babylonian rule instead of fleeing to Egypt. Ezekiel 29:6-9 denounces an alliance between Egypt and Israel that failed.

- Genesis 3:21 uses the word is katnot (כָּתְנוֹת) = long decorated garments, possibly tunics; not beged = any garment.

One thought on “Tazria: Mold or Mood?”