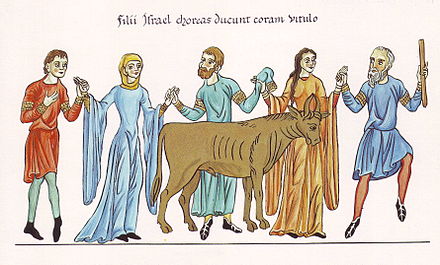

At the foot of Mount Sinai, the Israelites are worshiping the Golden Calf; at the summit, God is giving Moses a pair of stone tablets. It is a fateful day in this week’s Torah portion, Ki Tisa (Exodus 30:11-34:35).

Then [God] gave to Moses, once [God] finished speaking with him on Mount Sinai, the two tablets of the eidut, tablets of stone written by the finger of God. (Exodus 31:15)

eidut (עֵדֻת) = affidavit, pronouncement, testimony.

Why does God give Moses two engraved stone tablets to carry down from Mount Sinai?

To provide a written record of the laws?

In an earlier Torah portion, Mishpatim, God tells Moses:

“Come up to me on the mountain and be there, and I will give you tablets of stone and the instruction and the command that I have written to instruct them.” (Exodus 24:12)

What instruction and command? The book of Exodus never says what God wrote on the tablets. But in the book of Deuteronomy, Moses recites the “Ten Commandments”, then says:

These words God spoke to your whole assembly at the mountain, from the midst of the fire, the cloud, and the fog, in a great voice; and did not add more. And [God] wrote them on two tablets of stone, and gave them to me. (Deuteronomy 5:19)

However, these tablets are not the only written record of the Ten Commandments. They first appear in the book of Exodus, during God’s revelation at Mount Sinai.1 After the fireworks of the revelation are over, God adds 24 verses of rules for the people, from Exodus 20:19 in the Torah portion Yitro through Exodus 23:33 in the portion Mishpatim.

And Moses came and reported to the people all the words of God and all the laws, and all the people answered with one voice, and they said: “All the things that God has spoken, we will do!” And Moses wrote down all the words of God. (Exodus 24:3-4)

The next morning Moses sets up an altar, makes animal sacrifices, and splashes some of the blood on the altar.

Then he took the record of the covenant and he read it into the ears of the people, and they said: “All that God has spoken we will do and we will pay attention!” Then Moses took the blood and splashed it on the people, and said: “Hey! [This is] the blood of the covenant that God cut with you concerning all these words!” (Exodus 24:7-8)

So Moses writes a scroll containing the Ten Commandments and the many additional laws God communicated to him, and this scroll counts as a record of the covenant. The two stone tablets are not necessary for that purpose.

To test Moses?

The Torah portion Mishpatim ends with Moses climbing to the top of Mount Sinai alone. Moses spends forty days and forty nights in the cloud at the summit of Mount Sinai, listening to more instructions from God. This time the instructions are for making a portable tent-sanctuary, making vestments for priests, and ordaining the new priests.

Then God tells Moses that the people waiting at the foot of the mountain have made an idol.

And God spoke to Moses: “Go down! Because your people whom you brought up from the land of Egypt have ruined [everything]! They have been quick to turn aside from the way that I commanded them. They made themselves a cast image of a calf, and they prostrated themselves to it and they made slaughter sacrifices to it, and they said ‘This is your god, Israel, who brought you up from the land of Egypt’!” (Exodus 32:8)

After delivering the awful news, God tests Moses by making him an offer he can refuse:

“And now leave me alone, and my anger will flare up against them and I will consume them; and I will make you into a great nation.” (Exodus 32:10)

I think the God is implying: “If you leave me alone, then my anger will flare up against them and I will consume them.” It is a backhanded invitation to speak up.

Why does God add that if God “consumes” the Israelites, then Moses’ descendants will become a great nation instead? I suspect it is a temptation that God hopes Moses will reject. Moses passes the test; he argues that it would be a bad idea to destroy the Israelites, and God immediately backs off.

However, I think this is only the first part of God’s test of Moses. The second part is more subtle. By giving Moses the two stone tablets, God is handing over the responsibility for the covenant—the one that the people have just violated by making a golden idol.2 Since Moses wants the Israelites to become the people God will “make into a great nation”, let him address their flagrant violation of God’s law. God will stand by and watch what Moses does with the stone tablets.

Theoretically, Moses could leave the tablets at the top of Mount Sinai, go down and straighten out the Israelites, then fetch the tablets and present them to the people as a reward and confirmation that they are now on the right track. He rejects this option, probably because he knows he needs a strong visual aid to make the people pay attention to him.

He also needs to reinforce the idea that rewards and punishments come from God. Five times during the journey from Egypt to Mount Sinai, the Israelites blamed Moses for bringing them into the desert, and expected him, not God, to provide them with food and water.3 Each time Moses pointed out that God was the one in charge.

So Moses carries God’s two stone tablets down the mountain.

And it happened as he came close to the camp, and he saw the calf and circle-dancing; then Moses’ anger flared up; and he threw the tablets down from his hand, and he shattered them under the mountain. (Exodus 32:19)

Moses already knows about the Golden Calf. What enrages him now is the sight of the people drinking, singing, and dancing—enjoying themselves, now that they finally have a god they can understand, a god that inhabits a gold statue.

This kind of idol was standard in Egypt. Moses has been trying to get his people to accept a god who manifests only as cloud and fire. He would be angry, but not surprised, that the Israelites feel happy and relieved now that they have an idol. (He does not know that his own brother, Aaron, confirmed that the God who brought them out of Egypt inhabits the Golden Calf.)4

I doubt Moses is so completely overcome by his anger that he hurls down the tablets without thinking. After all, he had enough presence of mind to argue with God when he was surprised and frightened by his first overwhelming encounter at the burning bush. Surely he has enough presence of mind now, in a situation he is partially prepared for, to make a deliberate decision to smash the stones.

He may even worry that they will bounce instead of shatter, and fail to achieve the effects he desires: demonstrating that the people broke their covenant with God, inducing guilt, and setting an example regarding idols.

Demonstrating that they broke the covenant

None of the literate Israelites have time to read what is carved on the stones before Moses smashes them. But Moses waits until he is close enough so everyone can see that he is holding two thin, smooth stone tablets with writing carved into them. The Israelites would conclude that God must have given him the tablets at the top of the mountain. In the Ancient Near East, as in the modern world, both parties to a covenant get a written copy. So they would also assume, correctly, that the tablets are related to the covenant they made with God 40 days before.

In other words, the people would know that the stones were “two tablets of the eidut”, of God’s affidavit, pronouncement, or testimony. According to 12th-century commentator Ibn Ezra,

“He therefore broke the tablets which were in his hands and served, as it were, as a document of witness. Moses thus tore up the contract. As Scripture states, he did this in the sight of all of Israel.”5

Inducing guilt

The second effect Moses’ demonstration achieves is to make the Israelites realize they disobeyed God and did the wrong thing. According to 15th-century commentator Abravanel,

“Had Israel not seen the Tablets intact, the awesome work of the Lord, they would not have been moved by the fragments, since the soul is more impressed by what it sees, than by what it hears. He therefore brought them down from the mountain to show them to the people, and then break them before their very eyes.”6

The Israelites, like most humans, have a stronger and more visceral response to what they see than to any words they hear. The first time in Exodus that the people trust God (at least temporarily) is when they see the Egyptian charioteers drown in the Reed Sea.7 That is also the first time they rejoice, singing and dancing. The next time they rejoice, again with dancing, is in front of the Golden Calf.

But when they see the stone tablets carved with some words from God, and then see Moses shatter them, they know in their guts that they were wrong.

Setting an example regarding idols

The third effect Moses achieves by smashing the stone tablets is to set an example regarding idols. An idol, in the Hebrew Bible, is a physical object that is treated like a god. The Golden Calf is an idol. But the two stone tablets also have the potential to become an idol. What if the Israelites are so desperate for a concrete god that they adopt the tablets in place of the calf? What if they prostrate themselves before the tablets, make sacrifices to the tablets, and carouse in front of the tablets with the same unchecked ecstasy?

21st-century commentator Zornberg concluded:

“Moses, therefore, smashes the tablets, not in pique, but in a tragic realization that a people so hungry for absolute possession may make a fetish of the tablets as well.”8 When Moses hurls down the stone tablets, they do not bounce, like magical objects. They break, like slate tiles. The people see that the tablets are only stones. God does not inhabit them.

Change is hard. Human beings enjoy a little variety, but a change in employment or a change in address is hard to get used to even when it is an improvement. The Israelites were underdogs doing forced labor in Egypt. Now they have been changed into an independent people traveling toward a new home in Canaan. These changes alone require new habits of thought. But these people must also adopt a new religion.

The Israelites in Egypt still acknowledged the God of their ancestors Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. But now their God is demanding an active—and exclusive—form of religion. Instead of obeying their Egyptian overseers, they must obey an invisible God who manifests sometimes as cloud and fire, but speaks only to Moses. They must follow this God’s rules and do whatever God says. They promise twice that they will do it. But the new covenant is hard to obey.

I have managed big changes in my own life through a combination of stubborn determination to do the right thing and harnessing as much rational thought as I can. But I have advantages the Israelites did not have. I suffered only minor childhood trauma, I have lived safely in the American middle class, and I have an analytical personality and brain.

I want to feel sympathy, not anger, toward people whose choices seem blatantly wrong to me. But what if someday there is a moment when I could jolt people out of their habits of thought by smashing a potential metaphorical idol? If it ever happens, I hope I will recognize it.

- See my posts Yitro & Va-etchanan: Whose Words?, Part 1 and Part 2.

- The prohibition against making any idols or images of a god appears not only in the “Ten Commandments”, but also in Exodus 20:20, at the beginning of God’s long list of rules following the revelation, the list Moses has written down and read out loud to the people twice.

- Exodus 14:11-12, 15:22-24, 16:2-3, 16:6-8, 17:2-4.

- Exodus 32:4-5.

- Abraham ben Meir ibn Ezra, translation in www.sefaria.org.

- Don Isaac ben Judah Abravanel, translated by Aryeh Newman, in Nehama Leibowitz, Studies in Shemot, Part II, Maor Wallach Press, 1996, p. 610.

- Exodus 14:30-31, 15:19-21.

- Avivah Gottlieb Zornberg, The Particulars of Rapture, Doubleday, New York, 2001, p. 424.