The days are short and dark now, for those of us who live north of 45o in the northern hemisphere. But even at night we do not experience true darkness. A single lamp, a single flame, generates a lot of light.

Pitch darkness, the complete absence of light, means blindness at first, then death. Without light, no plants can live, and no living thing can survive. No wonder the first thing God creates in the book of Genesis is light.

And no wonder darkness is such a frightening plague in this week’s Torah portion, Bo (Exodus 10:1-13:16).

The darkness plague

Pharaoh does not let the Israelites leave Egypt until God has afflicted the land with ten miraculous disasters or plagues. The ninth plague is darkness.

Darkness is the only plague that does not bring death or disease to any living thing. Yet three days of utter darkness alarm Pharaoh and all the Egyptians more than anything but the tenth and final plague: death of the firstborn children.

And God said to Moses: “Stretch out your hand toward the heavens, and choshekh will be over the land of Egypt, a choshekh one can touch.” And Moses stretched out his hand toward the heavens, and there was a dark choshekh in all the land of Egypt for three days. No one could see his brother, and no one could get up from his spot for three days. But for all the Israelites, light was in their settlements. (Exodus 10:21-23)

choshekh (חֺשֶׁךְ) = darkness. (Like the word “darkness” in English, the word choshekh is used not only for the absence of physical light, but also for the absence of enlightenment or goodness.)

What is a darkness one can touch?

Medieval commentators wrote that the darkness was thick—a thing with its own palpable substance. Ibn Ezra wrote: “The Egyptians will feel the darkness with their hands.”1 Ramban described the darkness as “a very thick cloud that came down from heaven … which would extinguish every light, just as in all deep caverns.”2

And Rabbeinu Bachya explained: “The darkness was not a kind of solar eclipse. On the contrary, the sun operated completely normally during all these days. In fact, the whole universe operated normally; the palpable darkness was as if each individual Egyptian had been imprisoned all by himself in a black box. … Once this stage had been reached, God intensified this darkness to the extent that it was felt physically, preventing people from being able to move without ‘bumping’ into darkness at every move they tried to make.”3

Faced with this kind of darkness, the Egyptians stopped moving. No one got up for three days. People in the same room might speak to each other, but they could not help each other. So each one suffered alone; “no one could see his brother” (Exodus 10:23). If the plague had continued for a few additional days, all the Egyptians would have died of thirst by darkness.

19th-century rabbi Hirsch pointed out: “This plague was the most sweeping, in that it shackled the whole person, cutting him off from all fellowship and from all possessions, so that he could move neither his hands nor his feet to obtain the necessities of life.”4

As usual, Pharaoh asks Moses to beg his God to end the plague.

Then Pharaoh summoned Moses … (Exodus 10:24)

How does he summon anyone, when neither he nor any of his servants can “get up from his spot”? Perhaps the person who wrote down that verse did not think through the implications of the miraculous darkness. Or perhaps Moses has not left the palace courtyard since raising his hand to summon the darkness, and he can hear Pharaoh calling to him. Being an Israelite, Moses could still see and move, so he walks over to where Pharaoh sits. And he finds out whether Pharaoh is at last willing to let the Israelites go.

Darkness as metaphor

The Hebrew word choshekh, like the English word “darkness”, is used as a metaphor for gloominess, death, ignorance, or evil.

Since darkness means the absence of visible light, it also means ignorance, the absence of enlightenment.

Inform us of what we can say to [God]!

We cannot lay a case before him from a position of choshekh. (Job 37:19)

And in both Biblical Hebrew and English, light is associated with goodness, while darkness is associated with evil.

They forsake the paths of the upright

To go in the ways of choshekh. (Proverbs 2:13)

Pharaoh’s darkness

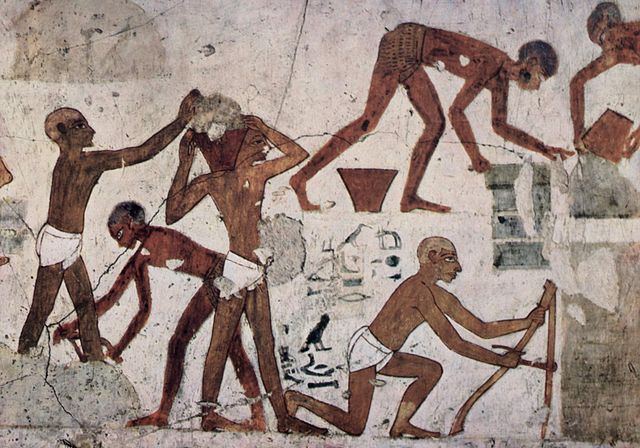

When Pharaoh’s father was on the throne (in Exodus 1:8-2:22), he conscripted all the Israelite men to do corvée labor on royal building projects.5 Corvée labor was common in the Ancient Near East, as common as governments conscripting their citizens into military service in modern times. But in the book of Exodus, the Israelites’ term of service never ends, under either the first pharaoh or his successor. Then God gets involved.

And the Israelites groaned under the servitude and they cried out. And their plea for rescue from the servitude went up to God. And God listened to their moaning … (Exodus 2:23-24)

The solution God devises is to send Moses to act as a prophet, and the plagues to force the new pharaoh to recognize the power of God and let the Israelites leave Egypt.

With each plague, Moses asks Pharaoh to let the Israelites go for at three-day walk into the wilderness to worship their God. Each time, Pharaoh refuses to give them even a few days off. They might as well be slaves.

If being in the dark is being unenlightened, blind to reality, Pharaoh always lives in darkness. He believes he can mistreat the Israelites without any personal consequences. He believes that their God, who keeps afflicting Egypt with disastrous miracles, cannot really destroy him or his kingdom.

Earlier in this week’s Torah portion, after Moses warns the court about the eighth plague, locust swarms, Pharaoh’s courtiers urge their king to give up.

And Pharaoh’s courtiers said to him: “How long will this be a trap for us? Let the men go so they can serve Y-H-V-H, their god! Don’t you realize yet that Egypt is lost?” (Exodus 10:7)

But Pharaoh still tries to bargain. He asks Moses which Israelites would go to worship Y-H-V-H, and Moses replies:

“With our young and with our old we will go, with our sons and with our daughters we will go, with our flocks and with our herds we will go, because it is our festival for God.” (Exodus 10:9)

Pharoah insists that he will let only the men go, so he and Moses are at an impasse again, and God sends the plague of darkness.

If darkness is a metaphor for evil, Pharaoh fits the bill. Not only does he refuse to give the Israelites even a few days off from work, he also increases their workload so it is impossible for them to meet their quotas.8 This gives his overseers a reason to whip them at any time.

Moses warns Pharaoh about each plague, but Pharaoh refuses, again and again, to let the Israelites go. This harms the native Egyptians, who suffer from thirst, vermin, agricultural collapse, and multiple diseases.

During the plague of darkness, Pharaoh summons Moses and says:

“Go, serve Y-H-V-H! Only your flocks and your herds must be left behind. Even your little ones may go with you!” (Exodus 10:24)

Pharaoh is still bargaining, but he has made a concession. Although he knows the Israelites will not come back, he is now willing to give up his free labor force—as long as they leave their livestock behind. Of course, he knows that the animals are the Israelites’ wealth and means of livelihood. And he probably doubts that they will get very far through the desert without at least the milk from their cattle, sheep, and goats.

But Pharaoh may also be considering the welfare of the native Egyptians for the first time. All of their livestock died during the fifth plague, cattle disease.5 The eighth plague, locust swarms, consumed the last green leaves in Egypt,6 so the Israelite livestock have nothing to eat (except for any hay the Egyptians might have stockpiled inside barns). But at least the Egyptians could eat the Israelites’ animals. The meat would keep them alive for a while, until Pharaoh came up with another plan.

Moses, however, refuses to make any concession to Pharaoh. He replies:

“You, even you, must place slaughter offerings and rising offerings in our hands, and we will make them for Y-H-V-H, our God. And also our property must go with us; not a hoof can remain behind …” (Exodus 10:25-26)

Then God steps in—or perhaps what steps in is Pharaoh’s pride and the power of habit.

Then Y-H-V-H strengthened Pharaoh’s mind, and he did not consent to let them go. (Exodus 10:27)

Three days of blindness and immobility are not enough to make Pharaoh completely change his mind. With the help of a little mind-hardening from God, Pharaoh holds out until his own firstborn son dies in the tenth plague, the one that God has planned all along as the finale.7

Does Pharaoh deserve the death of his firstborn son? Yes, the classic commentary answered, because Pharaoh is evil. (His son, and the other Egyptian firstborn and their parents, may be innocent. But the tales in the Torah focus on individual characters, using the reset of the people as background.)

Metaphorically speaking, Pharaoh always sits in darkness. No wonder he qualifies his permission to let the Israelites go, even after the life-threatening plague of darkness. No wonder God can easily harden his attitude so he refuses to let the Israelites take their livestock with them.

Darkness itself blinds and paralyzes him, but Pharaoh does not change his attitude. After all, he has lived in darkness his whole life.

One of the participants in a class I am teaching on Exodus pointed out that if you state a position once and get negative feedback, it is not too hard to change your mind. But if you stick with your unpopular opinion, it gets harder to change every time it is questioned. You find yourself fiercely defending your position to others—and refusing to reexamine it yourself.

Pharaoh’s mind keeps hardening because he is human. God’s assistance in hardening it is the human nature we are endowed with.

May we all pay attention to what we are doing, and seek enlightenment lest we slip into utter darkness.

- Abraham Ibn Ezra, 12th century, translation in www.sefaria.org.

- Ramban (Rabbi Moshe Nachman), 13th century, translation in www.sefaria.org.

- Rabbeinu Bachya ben Asher ibn Chalavah, 1255-1340, translation in www.sefaria.org.

- Rabbi Shimshon Rafael Hirsch, 19th century, The Hirsch Chumash: Sefer Shemot, translated by Daniel Haberman, Feldheim Publishers, Jerusalem, p. 144.

- The pharaoh in Exodus 1:8-2:22 also attempted to reduce the population of Israelites in Egypt by commanding the murder of male Israelite infants.

- Exodus 10:15.

- See God’s speech to Moses in Exodus 4:21-22.

- Exodus 1:8-22.