This week’s Torah portion, Vayechi (Genesis 47:28-50:26), begins:

And Jacob lived in the land of Egypt seventeen years; and the years of Jacob, the years of his life, were 147 years. The time for Israel to die approached, and he called for his son, for Joseph … (Genesis/Bereishit 47:28-29)

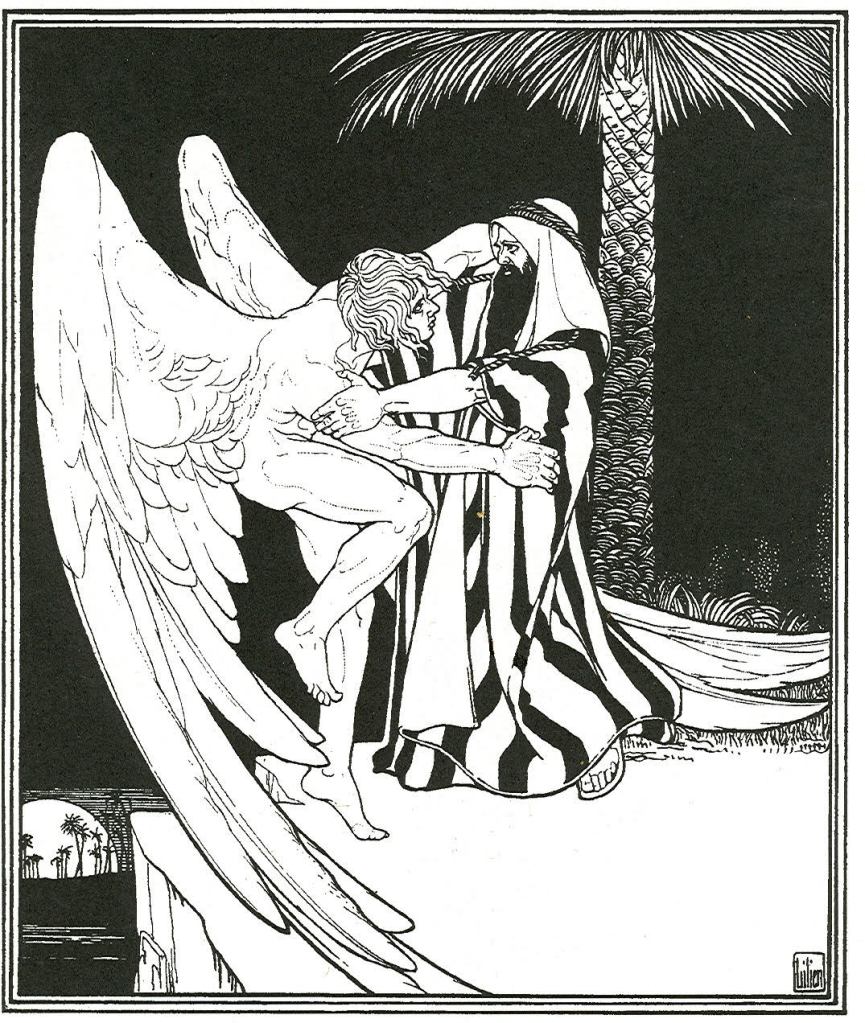

Jacob acquired a second name, Israel, in an earlier portion of the book of Genesis, Vayishlach, when he wrestled with a mysterious “man” all night before his reunion with Esau, the brother whom Jacob had cheated twenty years before.

Becoming Israel

In Vayishlach, Esau was approaching with 400 men, and Jacob was terrified that his brother would attack his camp for revenge. He prayed, he sent generous gifts ahead on the road, and he moved his whole household and all his possessions across the Yabok River. Then Jacob spent the night on the other side.

And Jacob was left alone. And a man wrestled with him until dawn rose. And he saw that he had not prevailed against [Jacob], so he touched the socket of his yareikh, and the socket of Jacob’s yareikh was dislocated when he wrestled with him. (Genesis 32:25-26)

yareikh (יָרֵךְ) = loin, i.e. hip, buttocks, upper thigh, or genitals (depending on the context).

One cannot actually touch the socket inside a human hip—unless, perhaps, one is a supernatural creature. Even with the pain of a dislocated hip, Jacob hangs onto his opponent. The mysterious wrestler is the first to speak.

Then he said: “Let me go, because dawn is rising.”

But [Jacob] said: “I will not let you go unless you bless me!”

And he said to [Jacob]: “What is your name?”

And he said: “Jacob.”

Then he said: “It will no longer be said that Jacob is your name, but Yisrael. Because sarita with God and with men, and you have prevailed.”

And Jacob inquired and said: “Please tell your name.”

And he said: “What is this, that you ask for my name!” (Genesis 32:27-29)

Yisrael (יִשְׂרָאֵל) = “Israel” in English. Possibly he strives with God, he contends with God. (Yisar,יִשַׂר = he strives with, he contends with + Eil, אֵל = God, a god.) On the other hand, the subject usually follows the verb in Biblical Hebrew, so Yisrael could mean “God contends”.)

sarita (שָׂרִיתָ) = you have striven with, you have contended. (From the same root as yisar.)

Gradually the “man” who wrestles with Jacob is revealed as a divine messenger. “Jacob was left alone”—away from any other human beings. “A man wrestled with him”—messengers from God often look like men at first, and can do physical things in our world.1 “You have striven with God and with men”—striving with God’s messenger is the equivalent of striving with God. And protesting that “you ask for my name!”—God’s messengers do not reveal their names in the Torah.2

The two wrestlers in this passage also serve as a metaphor for a narrow human frame of reference wrestling with a broad divine frame of reference—both within Jacob’s psyche. The divine perspective touches an intimate spot, and Jacob emerges from the experience with a new name, and a limp to remind him of what happened.

And the sun rose for him as he passed Penueil, and he, he was limping on his yareikh. (Genesis 32:32)

After this story, the Torah continues to use the name Jacob, but sometimes switches to Jacob’s new name, Israel. Why does it switch from “Jacob” to “Israel” at the beginning of this week’s portion, Vayechi?

Requesting an oath

The time for Israel to die approached, and he called for his son, for Joseph, and he said to him: “If, please, I have found favor in your eyes, please place your hand under my thigh. And do with me loyal-kindness and faithfulness: do not, please, bury me in Egypt! [When] I lie down with my fathers, then carry me out of Egypt and bury me in their burial site!” (Genesis 47:29-30)

This is Jacob/Israel’s first deathbed speech. As the self-centered Jacob, he might want to be buried in Bethlehem beside Rachel, the wife who died in childbirth, the wife he loved and mourned for the rest of his life. Or he might even want his sons to bury him in Egypt, where his entire surviving family has emigrated. His beloved son Joseph is a viceroy, so he could buy a deluxe burial site there.

But Jacob does not mention either possibility. As Israel, he knows it will be best for his future descendants if he is buried in the cave of Machpelah, which his grandfather Abraham purchased for a family burial site. This is where Abraham and Sarah, Isaac and Rebecca, and (we learn later in this Torah portion) Jacob’s first wife, Leah, are buried. Reinforcing the importance of that site, the only land in Canaan that his family inherits through the generations, will help Israel’s descendants in Egypt remember that someday they must return to Canaan to fulfill God’s prophecies.

Israel begins his speech to Joseph with extreme formality and politeness, addressing him in his role as the viceroy. The consensus among commentators is that the pharaoh does not want his invaluable viceroy to leave Egypt for even a short visit to Canaan, his homeland. What if Joseph did not return? So Israel decides to give Pharaoh an extra reason to let Joseph go to Machpelah. If Joseph has sworn the most solemn oath possible, how could Pharoah make his viceroy dishonor himself by violating it?

Precedent for the oath

So Israel requests the kind of oath that Abraham made his steward swear regarding a bride for his son Isaac. Jacob/Israel knows he will be powerless over his own burial; Abraham, at age 137, was afraid he would not live long enough to make sure his son married one of his relatives from Aram instead of a Canaanite. In both cases, the aged father relies on the most serious oath possible. Abraham told his steward:

“Please place your hand under my yareikh, and I will make you swear by God, god of the heavens and god of the earth, that you do not take a wife for my son from the daughters of the Canaanites amidst whom I am dwelling. Because you must go to my [former] land and to my relatives, and [there] you must take a wife for my son, for Isaac.” (Genesis 24:2-4)

Abraham’s steward asked a clarifying question to make sure he understood his mission. Then he complied at once with his master’s request:

And the servant placed his hand under the yareikh of Abraham, his master, and he swore to him on this matter. (Genesis 24:9)

Since the word yareikh could mean any of several locations on the lower body, we can only guess where Abraham’s steward placed his hand. But commentators have noted that the Latin root “testis” appears in words whose English versions are testify, testimony, and testicles, and claim that this may reflect a Roman practice of taking an oath on the genitals. And for at least two millennia, oaths administered by a court have required the person swearing the oath to hold a sacred item in the hand. Before the holy objects were made for the sanctuary, before the Torah was written down, a circumcised penis was the only sacred object available.3

The actual oath

In the portion Vayechi, Joseph listens to his father’s request, then tells him:

“I will do as you have spoken.” (Genesis 47:30)

Instead of immediately placing his hand under his father’s yareikh, Joseph makes a simple verbal promise. Is placing his hand under his father’s whatever-it-is beneath the dignity of a viceroy of Egypt?

Or does Joseph remember Jacob’s famous limp, and feel reluctant to touch the spot that the unnamed being touched?

Jacob does not accept Joseph’s unsupported promise as a bona fide oath.

He said: “Swear to me!” And he swore to him. Vayishtachu, Israel, at the head of the bed. (Genesis 47:31)

vayishtachu (וַיִּשְׁתַּחוּ) = and he prostrated himself, and he bowed as deeply as possible. (This verb is used for bowing to a king or to God.)

It sounds as though Joseph brings himself to place his hand under the spot and swear. His father, Israel, accepts Joseph’s response as a duly sworn oath, one that even the Pharaoh could not quibble about. And he bows as deeply as possible for an invalid in bed.

When Jacob limped toward Esau the morning after the wrestling match, he prostrated himself seven times—honoring his brother’s power over his life. Now Jacob prostrates himself as best he can, at age 147, to his Joseph—honoring his son the viceroy’s power.

Pharaoh’s permission

After that Israel rearranges his inheritance by adopting Joseph’s two sons as his own4 and makes two deathbed prophecies, one short5 and one lengthy.6 Then he repeats the instructions for his burial in the cave of Machpelah, and dies.7

Joseph has his father embalmed like an Egyptian nobleman, and then informs Pharaoh:

“My father made me swear, saying: ‘Here, I am dying. In my burial side that I dug for myself in the land of Canaan there you must bury me.’ And now please let me go up, and I will bury my father, and I will return.” And Pharaoh said: “Go up and bury your father as he made you swear.” (Genesis 50:5-6)

So Israel’s plan works.

A speculation

Yet Pharaoh gives Joseph permission to go even though Joseph does not mention the hand position he used for his oath to his father. Why is the placement of Joseph’s hand so important to his father?

I wonder if Israel wants Joseph to touch the same place the divine being touched. He might recognize himself in his favorite son. The first two times Joseph’s brothers came to Egypt, Joseph disguised himself and lied to them in order to get the information he wanted. When Jacob was a young man, he disguised himself and lied to his father in order to steal his brother’s blessing.

How can Israel get Joseph to recognize the manipulative side of his personality, and wrestle with it? Maybe if Joseph touches the spot that the divine being touched, it will shock him into the awareness that he is not as grand and impartial as he thinks. Joseph is the supreme judge of Egypt’s agricultural system, but he is not divine.

Would Jacob/Israel think in those terms? He is not a psychologist, but he is a clever thinker. And humans have always used symbolic acts to make connections between the known and the unknown. There is always more going on inside us than we know. Some people tend to act intuitively, and need to practice thinking and planning. Others are like Jacob, Joseph, and myself: thinking and planning are default behavior for us. We need to step back, take a breath, and take the long view. We need a touch of the divine.

- For example, divine messengers wash their feet and eat in front of Abraham in Genesis 18:1-8.

- See my posts Toledot & Vayishlach: Wrestlers, and Haftarat Naso—Judges: Spot the Angel.

- Talmud Bavli, Shevuot 38b; Rashi (11th-century Rabbi Shlomoh Yitzchaki); Rabbi Elie Munk, The Call of the Torah: Bereishis, Mesorah Publications, 1994, p. 626. See my post Chayei Sarah: A Peculiar Oath.

- Genesis 48:3-11, 48:22.

- The prophecy about Efrayim and Menasheh is in Genesis 48:12-20.

- The prophecy about the twelve tribes of Israel is in Genesis 49:1-28.

- Genesis 49:29-33.

Blessings stand upon the foundation of swearing oaths: בראשית\ברית אש. What’s the fire of the brit? Oaths. Proof: falsely sworn oaths caused the floods in the days of Noach.

I found this as I search for some explanations as to why the names Jacob and Israel are interchanged so many times in this parsha. I have read any number of explanations about the differences between the names and how they (possibly) stand for different sides of the man and how those differences live not just in him but in all his children (us, Jews). But the reason for the changes from one sentence to another I’m still searching for.

While I didn’t find the answer here, I found some fantastic Torah, and look forward to diving into your past and future posts. Thanks very much!